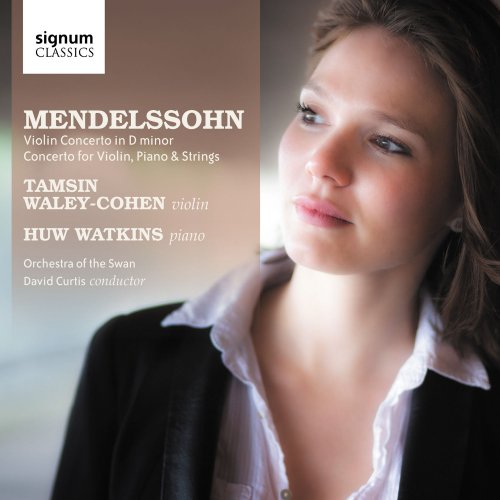

Tamsin Waley-Cohen - Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in D Minor, Concerto for Violin, Piano & String (2013) Hi-Res

Artist: Tamsin Waley-Cohen

Title: Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in D Minor, Concerto for Violin, Piano & String

Year Of Release: 2013

Label: Signum Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC 24bit-48kHz / FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 59:53

Total Size: 671 / 293 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in D Minor, Concerto for Violin, Piano & String

Year Of Release: 2013

Label: Signum Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC 24bit-48kHz / FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 59:53

Total Size: 671 / 293 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Felix Mendelssohn (1809 - 1847)

Violin Concerto in D Minor, MWV O3

1. I. Allegro09:12

2. II. Andante07:41

3. III. Allegro05:16

Double Concerto for Violin and Piano in D Minor, MWV O4

4. I. Allegro18:55

5. II. Adagio09:00

6. III. Allegro molto09:41

Performers:

Tamsin Waley-Cohen (Violin)

Huw Watkins (Piano)

Orchestra of the Swan

Conductor: David Curtis

Malcolm MacDonald’s notes trace a connection between Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in D Minor and the works of Giovanni Battista Viotti’s followers Rodolphe Kreutzer and the Pierres, Rode and Baillot, but also to the sensitive style of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. David Curtis and violinist Tasmin Waley-Cohen make these connections clear in Read more Sturm und Drang -like intensity. In the second movement, the closeness of the soloist to the microphones becomes especially noticeable in the heavy breathing that’s now become fashionable if not particularly palatable. (Listeners may want to ponder how close they’d have to sit to hear this in an orchestral concerto—probably close enough to feel the breath as well as hear it.) Nevertheless, behind that those intrusive breaths flows a rich lyricism, and the jaunty Finale provides an opportunity for Waley-Cohen to draw attention to the movement’s sparkling virtuosity. All the while, she draws a commanding (if a bit tubby) tone from the lower registers of the 1721 Fenyves Stradivari.

Pianist Huw Watkins joins Waley-Cohen in Mendelssohn’s Concerto for Violin and Piano, also in D Minor. The first movement of this work takes nearly as long as the whole of the early Violin Concerto; and it’s likely to strike listeners as not only longer but also more highly developed. After the introductory tutti, the piano enters first, and Watkins’s commanding bravura seems to set the bar very high, but Waley-Cohen matches him dramatically, tonally, and in expressive voltage, not only in the introduction but throughout the movement. Both soloists, as well as the orchestra, seem attuned to the foreshadowings of things to come in the loamiest passages in the movement’s central section. Here and there, a sort of roughness occurs in Waley-Cohen’s tone production, an effect compounded perhaps of her instrument’s timbre and her manner of drawing the sound from it, but this ruddiness may offend the sensibilities of only the rarest of listeners. In the slow movement, that tone takes on a mellifluous quality that serves the violin part well in achieving a musical equality with the piano, that is as engaging in lyrical dialogue here as in the first movement’s virtuosic passagework. The duo makes a strong case for the exhilarating Finale, combining its brilliance and its rhythmic vitality.

How long will it be before Mendelssohn’s early Violin Concerto becomes generally known as “Violin Concerto No. 1,” even though the composer didn’t publish it that way? There’s precedent for such retrospective meddling, as Bartók’s “Violin Concerto No. 1” or Maurice Ravel’s “Violin Sonata No. 1”—neither of which the composer published or numbered—attest. At least we haven’t yet heard of Beethoven’s “Violin Concerto No. 1 in C Major,” as we may in the future. Strongly recommended, and even more strongly for the early Violin Concerto than Alina Ibragimova’s less mellifluous performance with Vladimir Jurowski and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment on Hyperion 67795, which on its own merits I warmly recommended back in Fanfare. -- Robert Maxham

Pianist Huw Watkins joins Waley-Cohen in Mendelssohn’s Concerto for Violin and Piano, also in D Minor. The first movement of this work takes nearly as long as the whole of the early Violin Concerto; and it’s likely to strike listeners as not only longer but also more highly developed. After the introductory tutti, the piano enters first, and Watkins’s commanding bravura seems to set the bar very high, but Waley-Cohen matches him dramatically, tonally, and in expressive voltage, not only in the introduction but throughout the movement. Both soloists, as well as the orchestra, seem attuned to the foreshadowings of things to come in the loamiest passages in the movement’s central section. Here and there, a sort of roughness occurs in Waley-Cohen’s tone production, an effect compounded perhaps of her instrument’s timbre and her manner of drawing the sound from it, but this ruddiness may offend the sensibilities of only the rarest of listeners. In the slow movement, that tone takes on a mellifluous quality that serves the violin part well in achieving a musical equality with the piano, that is as engaging in lyrical dialogue here as in the first movement’s virtuosic passagework. The duo makes a strong case for the exhilarating Finale, combining its brilliance and its rhythmic vitality.

How long will it be before Mendelssohn’s early Violin Concerto becomes generally known as “Violin Concerto No. 1,” even though the composer didn’t publish it that way? There’s precedent for such retrospective meddling, as Bartók’s “Violin Concerto No. 1” or Maurice Ravel’s “Violin Sonata No. 1”—neither of which the composer published or numbered—attest. At least we haven’t yet heard of Beethoven’s “Violin Concerto No. 1 in C Major,” as we may in the future. Strongly recommended, and even more strongly for the early Violin Concerto than Alina Ibragimova’s less mellifluous performance with Vladimir Jurowski and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment on Hyperion 67795, which on its own merits I warmly recommended back in Fanfare. -- Robert Maxham

![Ex Novo Ensemble - OSVALDO COLUCCINO: Emblema (2018) [Hi-Res] Ex Novo Ensemble - OSVALDO COLUCCINO: Emblema (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/22/ot6pocjri3hisq06iz4768yl5.jpg)

![Chris Forsyth's WHAT IS NOW - Both / And (2026) [Hi-Res] Chris Forsyth's WHAT IS NOW - Both / And (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771839412_cover.jpg)

![Sinedades - De par en par (2026) [Hi-Res] Sinedades - De par en par (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/23/k9xyrl2p7m3kmcwozolhfnu7a.jpg)

![Julian Lage - Scenes From Above (Japanese Edition Bonus Track) (2026) [SHM-CD] Julian Lage - Scenes From Above (Japanese Edition Bonus Track) (2026) [SHM-CD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1772029332_front.jpg)