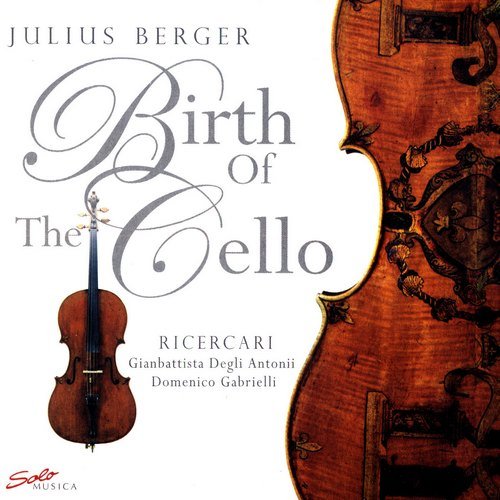

Julius Berger - Birth of the Cello (2007)

Artist: Julius Berger

Title: Birth of the Cello

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Solo Musica

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:14:30

Total Size: 358 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Birth of the Cello

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Solo Musica

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:14:30

Total Size: 358 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01-12 Gianbattista Degli Antonii - Ricercatas Nos. 01-12

13-19 Domenico Gabrielli - Ricercari Nos. 01-07

Performers:

Julius Berger - violoncello

This CD is offered as a discovery and presentation of the first solo works for the cello, played on the oldest surviving instrument. If that sounds like a somewhat dry proposition – and the chief appeal will undoubtedly be to specialists and musicologists – there is, nevertheless, enough here to provide enjoyment for the general listener, especially the listener who is already acquainted with Bach’s solo Cello Suites.

The whole feel of this recording is that nothing has been spared to make the programme attractive. So detailed and scholarly is the booklet of notes that it might well pass for a learned journal – and so large (48 pages) that it would scarcely have fitted into a normal plastic CD case. The disc is presented in a cardboard case in the form of a triptych, with the booklet slotted into the left-hand leaf and the CD in the right-hand. An illustration of the decorated rear of a cello – presumably, Julius Berger’s own Carlo IX Amati instrument – is spread across the left and centre leaves of the case, with sections of the same illustration on the cover and on the CD itself.

This Amati cello undoubtedly provides much of the interest, so it is not surprising that a considerable portion of the notes should be devoted to its history. Made in Cremona in 1566, at the beginning of the slow transition from the viola da gamba to the cello, it soon became an integral part of the court orchestra of Charles IX. In the hands of private owners after the French Revolution, its existence remained unknown until 1926 when it was identified by a distinguished English violin maker.

Julius Berger first encountered the instrument in the 1980s; re-encountering it in 2004, he realised that he had finally discovered his ideal instrument, one whose sound spoke directly to the heart of the listener. Far from being merely the ‘spin’ of Berger’s publicity team, the sound on the CD bears out these claims, aided by a bright and immediate recording.

The quality of the cello works of Antonii and Gabrielli was recognised at least as long ago as 1947: “[W]ith Gabrielli the literature for unaccompanied cello took its first strides in some remarkable compositions which stand stylistically, like those of Antonii, on the borderline of middle and late baroque periods.” (Bukofzer, Manfred R, Music In The Baroque Era From Monteverdi To Bach (New York: Norton, 1947) p.139)

Julius Berger, who combines the roles of distinguished academic and public performer, has long been a student of their works and has annotated their music. Frustrated in his attempts to persuade others, he was finally able at the 2006 Asiago Festival to perform Gabrielli’s Ricercari in a programme together with the Preludes of Sofia Gubaidulina, whose appreciation of his playing is noted in the booklet.

The Solo Musica website – in German only – describes this 2006 event as a fascinating experience which encouraged the hope that the music of Gabrielli and Antonii may finally, after almost 350 years, be appreciated. In case Solo Musica and I have given the impression that this CD breaks completely new ground, I should point out the existence of an earlier recording of these works by Jerôme Pernoo on the Ogam label (488 0152 – no longer available in the UK); I have not heard it or seen any reviews of it, and I cannot imagine that it improves on Berger’s performances.

Berger himself refers to the fascination of playing this music on the oldest surviving cello and his wish for the audience to experience something similar, akin to what Bach referred to as Recreation des Gemüths – recreation of the soul, as the English translation has it, though Gemüth means much more than that: spiritual satisfaction might be nearer to the mark.

Berger certainly achieves that aim in large measure for me; his playing throughout this recording is excellent. All the praise which my colleague MC heaped on his performances of Boccherini and Leo applies equally to his performances here (Classical Cello Concertos, Brilliant Classics 92198 – see review; JW was slightly less impressed – see review). My only caveat is that most listeners will find it much easier to engage with the concertos on that set than with the solo cello music on offer here. Make the effort, however, and you will be rewarded – especially if you follow the notes and music examples in the booklet. If in doubt, go to the Solo Musica website and click on hören und kaufen to hear some examples.

The Antonii Ricercate are of chiefly academic interest. Though I don’t wish to suggest that they are dry – certainly not as dry as those early ricercari which the Oxford Companion to Music rates as “artistically on a par with Czerny’s duller technical studies” (p.1060) – they do remind us that the basic meaning of ricercar is a piece designed to try out the range and capabilities of an instrument. (See Concise Grove, s.v. ricercar). Originally published as ricercate sopra il violoncello o’ clavicembalo, i.e. for cello or keyboard, their publication – and probably their composition – predates the Gabrielli works, which are often regarded as the first solo cello pieces. Berger’s notes dismiss the suggestion sometimes made that they were intended for performance by cello and harpsichord, though I suspect that many listeners would appreciate the greater variety of such an arrangement – or, indeed, Antonii’s own arrangement for violin and harpsichord.

I suspect that most listeners will, like me, be more attracted to the Gabrielli works than to the Antonii. Degli Antonii does not warrant an entry in either the Concise Grove or the Oxford Companion. Gabrielli does (see Concise Grove s.v. Domenico Gabrielli and the Oxford Companion, p.500.) You may well not have encountered either composer before, but an attractive Trumpet Sonata by Gabrielli is included on a Naxos CD of Baroque Trumpet music which I reviewed in September, 2007 (8.570501 – see my review, also GPu’s review). The Ricercari may not be as attractive as that concerto, but they are well worth hearing.

I cannot imagine that this Solo Musica disc will form a regular part of my listening programme or that this is the most vital Baroque CD ever, but its value is certainly more than that of a mere historical curiosity. It left me feeling academically informed and entertained in equal measures. -- Brian Wilson

The whole feel of this recording is that nothing has been spared to make the programme attractive. So detailed and scholarly is the booklet of notes that it might well pass for a learned journal – and so large (48 pages) that it would scarcely have fitted into a normal plastic CD case. The disc is presented in a cardboard case in the form of a triptych, with the booklet slotted into the left-hand leaf and the CD in the right-hand. An illustration of the decorated rear of a cello – presumably, Julius Berger’s own Carlo IX Amati instrument – is spread across the left and centre leaves of the case, with sections of the same illustration on the cover and on the CD itself.

This Amati cello undoubtedly provides much of the interest, so it is not surprising that a considerable portion of the notes should be devoted to its history. Made in Cremona in 1566, at the beginning of the slow transition from the viola da gamba to the cello, it soon became an integral part of the court orchestra of Charles IX. In the hands of private owners after the French Revolution, its existence remained unknown until 1926 when it was identified by a distinguished English violin maker.

Julius Berger first encountered the instrument in the 1980s; re-encountering it in 2004, he realised that he had finally discovered his ideal instrument, one whose sound spoke directly to the heart of the listener. Far from being merely the ‘spin’ of Berger’s publicity team, the sound on the CD bears out these claims, aided by a bright and immediate recording.

The quality of the cello works of Antonii and Gabrielli was recognised at least as long ago as 1947: “[W]ith Gabrielli the literature for unaccompanied cello took its first strides in some remarkable compositions which stand stylistically, like those of Antonii, on the borderline of middle and late baroque periods.” (Bukofzer, Manfred R, Music In The Baroque Era From Monteverdi To Bach (New York: Norton, 1947) p.139)

Julius Berger, who combines the roles of distinguished academic and public performer, has long been a student of their works and has annotated their music. Frustrated in his attempts to persuade others, he was finally able at the 2006 Asiago Festival to perform Gabrielli’s Ricercari in a programme together with the Preludes of Sofia Gubaidulina, whose appreciation of his playing is noted in the booklet.

The Solo Musica website – in German only – describes this 2006 event as a fascinating experience which encouraged the hope that the music of Gabrielli and Antonii may finally, after almost 350 years, be appreciated. In case Solo Musica and I have given the impression that this CD breaks completely new ground, I should point out the existence of an earlier recording of these works by Jerôme Pernoo on the Ogam label (488 0152 – no longer available in the UK); I have not heard it or seen any reviews of it, and I cannot imagine that it improves on Berger’s performances.

Berger himself refers to the fascination of playing this music on the oldest surviving cello and his wish for the audience to experience something similar, akin to what Bach referred to as Recreation des Gemüths – recreation of the soul, as the English translation has it, though Gemüth means much more than that: spiritual satisfaction might be nearer to the mark.

Berger certainly achieves that aim in large measure for me; his playing throughout this recording is excellent. All the praise which my colleague MC heaped on his performances of Boccherini and Leo applies equally to his performances here (Classical Cello Concertos, Brilliant Classics 92198 – see review; JW was slightly less impressed – see review). My only caveat is that most listeners will find it much easier to engage with the concertos on that set than with the solo cello music on offer here. Make the effort, however, and you will be rewarded – especially if you follow the notes and music examples in the booklet. If in doubt, go to the Solo Musica website and click on hören und kaufen to hear some examples.

The Antonii Ricercate are of chiefly academic interest. Though I don’t wish to suggest that they are dry – certainly not as dry as those early ricercari which the Oxford Companion to Music rates as “artistically on a par with Czerny’s duller technical studies” (p.1060) – they do remind us that the basic meaning of ricercar is a piece designed to try out the range and capabilities of an instrument. (See Concise Grove, s.v. ricercar). Originally published as ricercate sopra il violoncello o’ clavicembalo, i.e. for cello or keyboard, their publication – and probably their composition – predates the Gabrielli works, which are often regarded as the first solo cello pieces. Berger’s notes dismiss the suggestion sometimes made that they were intended for performance by cello and harpsichord, though I suspect that many listeners would appreciate the greater variety of such an arrangement – or, indeed, Antonii’s own arrangement for violin and harpsichord.

I suspect that most listeners will, like me, be more attracted to the Gabrielli works than to the Antonii. Degli Antonii does not warrant an entry in either the Concise Grove or the Oxford Companion. Gabrielli does (see Concise Grove s.v. Domenico Gabrielli and the Oxford Companion, p.500.) You may well not have encountered either composer before, but an attractive Trumpet Sonata by Gabrielli is included on a Naxos CD of Baroque Trumpet music which I reviewed in September, 2007 (8.570501 – see my review, also GPu’s review). The Ricercari may not be as attractive as that concerto, but they are well worth hearing.

I cannot imagine that this Solo Musica disc will form a regular part of my listening programme or that this is the most vital Baroque CD ever, but its value is certainly more than that of a mere historical curiosity. It left me feeling academically informed and entertained in equal measures. -- Brian Wilson

![Meinild/Anderskov/Tom - Spectral Entanglements (2023) [Hi-Res] Meinild/Anderskov/Tom - Spectral Entanglements (2023) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771491474_hl116k2q9n24a_600.jpg)