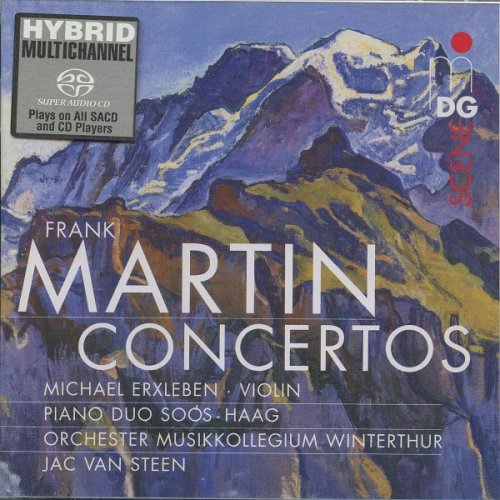

Michael Erxleben, Orchester Musikkollegium Winterthur, Jac van Steen - Frank Martin: Concertos (2004) [SACD]

Artist: Michael Erxleben, Orchester Musikkollegium Winterthur, Jac van Steen

Title: Frank Martin: Concertos

Year Of Release: 2004

Label: MDG Scene

Genre: Classical, Orchestral, Violin, Piano

Quality: DSD64 image (*.iso) / 2.0, 5.1 (2,8 MHz/1 Bit)

Total Time: 01:04:20

Total Size: 3.33 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Frank Martin: Concertos

Year Of Release: 2004

Label: MDG Scene

Genre: Classical, Orchestral, Violin, Piano

Quality: DSD64 image (*.iso) / 2.0, 5.1 (2,8 MHz/1 Bit)

Total Time: 01:04:20

Total Size: 3.33 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Violin Concerto

1. Allegro tranquillo - 12:34

2. Andante molto moderato - 10:10

3. Presto - 06:46

Concerto for 7 wind instruments (timpani, percussion & string orchestra)

4. Allegro - 06:40

5. Adagietto - 06:40

6. Allegro vivace - 07:18

7. Danse de la Peur, for 2 pianos & small orchestra (from the ballet "Die blaue Blume") - 14:17

Frank Martin (pronounced, in the French way, Frahnk Mar-TAN) has a complex artistic history. Born in Geneva, Martin (1890-1974) grew up in, at the time, a German musical culture. It took conductor Ernest Ansermet to introduce and establish French composers in Swiss concert repertory. Martin's earliest music reflected German taste, especially a life-long inspiration of J. S. Bach. He eventually became one of the great composers of sacred music in the Modern era. By the Twenties, however, he had accommodated French Impressionist harmony into his language without ever quite becoming an Impressionist. Martin had no formal training as a composer. He worked on his own, and he kept his independence throughout his life. For example, he became interested in certain ideas of Arnold Schoenberg but never went over to atonality. He remained steadfast in his belief in harmony as the strongest musical element. Over the years, his idiom changed several times, which makes him hard to classify, something that may account for his relative neglect among musicologists. Nevertheless, great musicians continue to program his music.

The Swiss composer Frank Martin travelled widely throughout Europe, gaining a rich awareness of prevailing musical styles, and these experiences had a strong influence on his approach to composition. Maurice Ravel was probably the contemporary figure with whom he felt the closest affinity, and Bach the master for whom he had the greatest reverence.

The collection gathered here makes a compelling combination. These three concertante pieces each bring their own particular slant on the medium. To a large extent this is because the performing resources required are so different from one piece to the next. But in each case Martin shows his mastery of the musical demands.

The earliest of these pieces is Danse de la peur, of 1936. This is a single movement composition, for two pianos and small orchestra. The dynamic range is wide, so too the range of tempi. While the ensemble is described as a ‘small orchestra’, there is no lack of variety, and the music certainly packs a punch. The recorded sound is excellent, as it is in the other pieces.

The Concerto for seven wind instruments, timpani, percussion and strings dates from 1949 and adopts the traditional three-movement plan. There are plenty of different instrumental colours and combinations, of course, and Martin exploits these various options with both imagination and rhythmic freedom. With seven solo wind instruments the choices of priority are numerous; so much to that this becomes a most unconventional concerto, a kind of concerto for orchestra minus the string section. Be that as it may, the results are compelling, with excellent opportunities shared around the ensemble.

There are three movements, each of some seven minutes, on the conventional fast-slow-fast design. All praise to the members of the Musikcollegium Winterthur, whose performance is fresh, spontaneous, and virtuoso too.

On the face of it, the Violin Concerto of 1951 is the most traditional of these three pieces, since it has a three-movement plan and a more conventional relationship between solo and ensemble. As the music evolves, so it becomes evident that Martin has adapted these procedures in his own way. For instance, the recapitulation of the first movement’s principal themes comes not within that movement but later in the work, as if to set the seal of unity on the whole conception. Moreover, the third theme becomes the basis of the passacaglia that lies at the heart of the second movement, while the second theme is treated fugally in the development section that lies at the heart of the finale. Does all this sound too clever by half? If it does, do not be fooled; for the music sounds fresh and spontaneous in every bar.

The Violin Concerto, in common with the distinctive masterpieces associated with Martin’s genre, is a particularly poetic work. It is appropriate therefore that Michael Erxleben makes a compelling soloist, at once lyrical and strong, as the score demands.

Terry Barfoot

The Swiss composer Frank Martin travelled widely throughout Europe, gaining a rich awareness of prevailing musical styles, and these experiences had a strong influence on his approach to composition. Maurice Ravel was probably the contemporary figure with whom he felt the closest affinity, and Bach the master for whom he had the greatest reverence.

The collection gathered here makes a compelling combination. These three concertante pieces each bring their own particular slant on the medium. To a large extent this is because the performing resources required are so different from one piece to the next. But in each case Martin shows his mastery of the musical demands.

The earliest of these pieces is Danse de la peur, of 1936. This is a single movement composition, for two pianos and small orchestra. The dynamic range is wide, so too the range of tempi. While the ensemble is described as a ‘small orchestra’, there is no lack of variety, and the music certainly packs a punch. The recorded sound is excellent, as it is in the other pieces.

The Concerto for seven wind instruments, timpani, percussion and strings dates from 1949 and adopts the traditional three-movement plan. There are plenty of different instrumental colours and combinations, of course, and Martin exploits these various options with both imagination and rhythmic freedom. With seven solo wind instruments the choices of priority are numerous; so much to that this becomes a most unconventional concerto, a kind of concerto for orchestra minus the string section. Be that as it may, the results are compelling, with excellent opportunities shared around the ensemble.

There are three movements, each of some seven minutes, on the conventional fast-slow-fast design. All praise to the members of the Musikcollegium Winterthur, whose performance is fresh, spontaneous, and virtuoso too.

On the face of it, the Violin Concerto of 1951 is the most traditional of these three pieces, since it has a three-movement plan and a more conventional relationship between solo and ensemble. As the music evolves, so it becomes evident that Martin has adapted these procedures in his own way. For instance, the recapitulation of the first movement’s principal themes comes not within that movement but later in the work, as if to set the seal of unity on the whole conception. Moreover, the third theme becomes the basis of the passacaglia that lies at the heart of the second movement, while the second theme is treated fugally in the development section that lies at the heart of the finale. Does all this sound too clever by half? If it does, do not be fooled; for the music sounds fresh and spontaneous in every bar.

The Violin Concerto, in common with the distinctive masterpieces associated with Martin’s genre, is a particularly poetic work. It is appropriate therefore that Michael Erxleben makes a compelling soloist, at once lyrical and strong, as the score demands.

Terry Barfoot

![Michael Erxleben, Orchester Musikkollegium Winterthur, Jac van Steen - Frank Martin: Concertos (2004) [SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2022-01/1641993089_back.jpg)

![Mona Krogstad - Serenity Now (2026) [Hi-Res] Mona Krogstad - Serenity Now (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771330367_folder.jpg)

![Igor Senderov - Verso la luce (2026) [Hi-Res] Igor Senderov - Verso la luce (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/15/7c9jtbvl2o5b7e8imwebziodn.jpg)

![Jacob Anderskov - Vinterstemmer (2026) [Hi-Res] Jacob Anderskov - Vinterstemmer (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771036914_d0s5qxbxc5g5l_600.jpg)