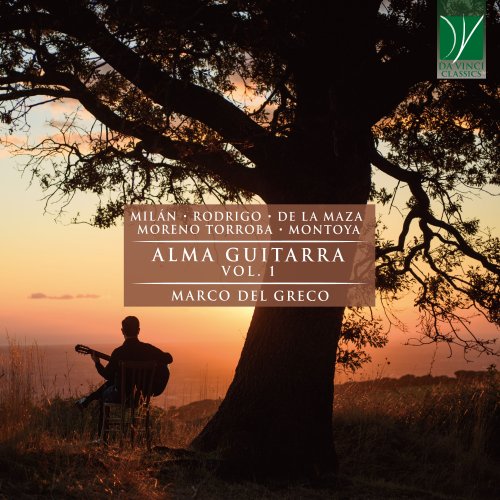

Marco Del Greco - Milán, Rodrigo, Torroba, Moreno, Sainz de la Maza- Alma Guitarra, Vol. 1 (2022)

Artist: Marco Del Greco

Title: Milán, Rodrigo, Torroba, Moreno, Sainz de la Maza- Alma Guitarra, Vol. 1

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 52:21 min

Total Size: 212 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Milán, Rodrigo, Torroba, Moreno, Sainz de la Maza- Alma Guitarra, Vol. 1

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 52:21 min

Total Size: 212 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Fantasia X (Transcription by Marco Del Greco)

2. Tiento antiguo

3. Zarabanda lejana (Homenaje a la Vihuela de Luis Milán)

4. En los trigales

5. Nocturno

6. Suite castellana: I. Fandanguillo

7. Suite castellana: II. Arada

8. Suite castellana: III. Danza

9. Burgalesa

10. Canciones castellanas

11. Rondeña

12. Petenera

13. El Vito

14. Rondeña (Arrangement by Marco Del Greco)

The project

In the summer of 1827, Alessandro Manzoni felt the need to stay in Florence (on the Arno’s banks, “in whose waters I washed my rags”, as he wrote). He acknowledged that the language spoken by the people of Tuscany was the model to be adopted in order to give a purer linguistic style to his novel I promessi sposi (“The Bethroted”), a masterpiece of Italian literature.

A similar necessity led me, in this period of my artistic research, to turn toward the places where the modern guitar has its deepest roots. The three main sources (as concerns instrument-building, interpretation, and composition) whence the rebirth of this instrument would spring at the beginning of the twentieth century are in fact found in Spain. They are represented, in these three different fields, by Antonio de Torres, Francisco Tárrega, and Manuel De Falla.

Luthier Antonio de Torres was born in Almería in 1817. He is universally acknowledged as the Stradivari of the guitar. He is the one who could conceive and realize a new, modern, and revolutionary sound ideal of this instrument, thanks to his continuing experimentations. These have at their ultimate goal the building of instruments capable of emitting all the fundamental frequencies, from the lowest to the highest, and having a very rich timbral palette, hitherto unheard-of. His guitars would be taken as examples by luthier Manuel Ramírez. In his taller in Madrid the most important luthiers (i.e. guitarreros) of the first half of the twentieth century would be educated.

Francisco Tárrega, who lived up to the first years of the twentieth century, played on Torres’ guitars. Through his compositions and transcriptions, but even more through his pedagogical activity, he laid the foundations on which the modern guitar technique would take shape. This technique be transmitted by his most important students, both direct and indirect.

The Homenaje for guitar, written by Manuel de Falla in 1920 to pay homage to Claude Debussy’s death, would instead be the spark literally igniting, for the first time in guitar’s history, the interest of “non-guitarist” composers toward this instrument. Within an unbelievably short time, this would lead to the birth of a repertory exceptional in quantity and quality.

The project “Alma Guitarra” starts from here, and is centered on the rediscovery of the guitar’s authentic sound in those so fundamental years. Then, unbelievable talents in the fields of instrument-making, composition, and interpretation, led to such extraordinary results.

This research is directed toward the instrument’s deepest soul, and toward its unbelievable generating power, reaching present-day from the beginning of the twentieth century. The word “alma” takes here a double meaning. In Spanish, it means “soul”; in Latin, it derives from the verb alere, “to nourish, to give life”.

For this recording, I employed three guitars built between 1916 and 1942 by the greatest masters of instrument-making of the Madrid school, i.e. Manuel Ramírez and Santos Hernandez. The choice of these precious instruments was the direct consequence of my research. Each guitar was assigned to its repertoire, by degrees of timbral affinity and of similar character.

However, guitars without strings produce no sounds. It is precisely from the union between wood and the means putting it into vibration that the mysterious fascination of the guitar is born. The strings are therefore a fundamental part of the project. I used gut strings for the trebles, and strings of a particular synthetic silk wound for the basses. Up to approximately 1947, prior to the discovery of nylon and its use as the material for musical strings, the only material employed for the production of the guitar’s trebles had always been gut. Therefore, luthiers, composers, and especially performers grew up on the basis of this kind of string. It has its limits, mainly as concerns duration and reliability, but it has a colour and an expressivity which are very different with respect to modern nylon. For the basses, instead, a silk core was employed; here too, it would later by replaced by a flock of nylon. The sound of strings with a silk core is characterized by a much deeper, darker and less metallic sound with respect to the later strings with nylon core. This combination between strings and instruments leads not to homogeneity, therefore, but rather to an extreme timbral differentiation of the six strings. Each of them will then represent a different and perfectly recognizable voice of its own.

The repertory

It may seem unusual, at first sight, to find a Renaissance Fantasia, originally written for vihuela, at the beginning of an album focusing on the guitar repertoire of the Spanish twentieth century between the two Wars. Actually, in precisely those same years when this enormous mass of new repertoire was being created, the music written since the early sixteenth century was being rediscovered. These pieces were transcribed from ancient tablatures, and had been conceived for instruments such as the lute, the Baroque guitar and the vihuela de mano. This “new” music would represent a great stimulus for the guitarists and composers of the time.

Luys Milán has been one of the most important vihuelists. His only work, Libro de música de vihuela de mano intitulado el Maestro, published in Valencia in 1536, is the first written testimony of the vihuela repertoire to have been preserved. Milán’s music is highly original, and Fantasía X demonstrates this. It contains two typical traits of his writing: there are passages of consonancias (i.e. chords of simultaneous sounds, with few polyphonic elements) constantly alternating with redobles (quick ascending and descending scales with an improvisational character). They also demonstrate a very high level of development in the instrumental technique.

In the same region of Valencia was born also Joaquín Rodrigo. Among the non-guitarist composers, he certainly was the most deeply fascinated by this early repertoire. Indeed, his first work for solo guitar, written in 1926, i.e. his Zarabanda lejana (Distant Sarabanda), was subtitled as a “Homenaje a la vihuela de Luis Milán”. This influence can be found perhaps to an even higher degree in his Tiento Antiguo of 1942, following immediately Milán’s Fantasía in this album. The tiento is in fact an early musical form similar to the Toccata, employed by sixteenth-century vihuelists. I meant here to create a sort of diptych. En los Trigales (“In the wheat fields”), written in 1938, is instead a piece in a simple ABA form. The first section has a dancing character, and the second an intensely descriptive quality.

A composer from Madrid, Federico Moreno Torroba approached the guitar around the year 1920, prompted by the Andalusian guitarist Andrés Segovia, who at the time was 27 years old. Segovia was beginning, at that time, to explore the interest of composers who could write new works dedicated to him. The Danza castellana would later become, in 1926, the third and last movement of the Suite castellana, with the mere title of “Danza”. It is the first fruit born from this prolific cooperation. Even though Segovia always stated that this piece had been written by Moreno Torroba in 1919, recent studies demonstrated beyond any doubt that its composition date has to be postponed to the first months of 1921, or, at the limit, to December 1920 (i.e. after de Falla’s Homenaje). From the interpretive viewpoint. The Suite Castellana accompanied Segovia throughout his long and phenomenal concert activity. However, curiously, we have no discographic witness of his interpretation of the Danza. The Nocturno is a piece with an Impressionist inspiration. Here, stupendous timbral intuitions are joined with a more clearly “French” harmonic taste. The Burgalesa has been recorded here in its original key, F# major, rather than in the adaptation made by Segovia (in E major); it is a song inspired by the Castilian city of Burgos.

In Burgos was born, in 1896, Regino Sainz de la Maza. He was a guitarist, composer, and, since 1935, the first professor of guitar at the “Real Conservatorio Superior de Música” of Madrid. He was a pupil of Daniel Fortea, who had been in turn a student of Tárrega. Starting in the 1920s, he began an extraordinary career as a concert musician. Its summit was reached in 1940 when he premiered the famous Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra by Joaquín Rodrigo. He was also the dedicatee of this work. The premiere took place on a Santos Hernandez guitar in maple wood, similar to the one I use in this recording, with gut strings. Alirio Díaz, who had been his student at the Madrid Conservatory in the 1950s, remembered him as a sublime composer and a genius guitarist. Most of his works were published at a later date with respect to their composition. This can be deduced from the programs of his recitals and from some recordings. The pieces can therefore be dated back to the time I am taking into account, between the Twenties and the Forties. I recorded here his selection of arrangements after Castilian songs, as well as three pieces with an exquisitely Andalusian inspiration. These are the Rondeña (published in a preceding version with the title of Andaluza), a Petenera, and his very effectful version for solo guitar of the folksong El Vito.

By way of conclusion, in the fashion of a concert’s encore, and in order to remain within the Andalusian context, I added a version of my own after the famous Flamenco Rondeña written by the father of the modern Flamenco guitar, i.e. Ramón Montoya. This piece had been immortalized in a historical recording of 1936 on a Santos Hernandez guitar with – of course – gut strings.

The recording was realised in Sermoneta, in the 11th-century Church of St. Michael Archangel. No digital reverb has been added, in order to reproduce, at its best, the sound of these wonderful instruments, built by the knowledgeable hands of these great luthiers.

Marco Del Greco

In the summer of 1827, Alessandro Manzoni felt the need to stay in Florence (on the Arno’s banks, “in whose waters I washed my rags”, as he wrote). He acknowledged that the language spoken by the people of Tuscany was the model to be adopted in order to give a purer linguistic style to his novel I promessi sposi (“The Bethroted”), a masterpiece of Italian literature.

A similar necessity led me, in this period of my artistic research, to turn toward the places where the modern guitar has its deepest roots. The three main sources (as concerns instrument-building, interpretation, and composition) whence the rebirth of this instrument would spring at the beginning of the twentieth century are in fact found in Spain. They are represented, in these three different fields, by Antonio de Torres, Francisco Tárrega, and Manuel De Falla.

Luthier Antonio de Torres was born in Almería in 1817. He is universally acknowledged as the Stradivari of the guitar. He is the one who could conceive and realize a new, modern, and revolutionary sound ideal of this instrument, thanks to his continuing experimentations. These have at their ultimate goal the building of instruments capable of emitting all the fundamental frequencies, from the lowest to the highest, and having a very rich timbral palette, hitherto unheard-of. His guitars would be taken as examples by luthier Manuel Ramírez. In his taller in Madrid the most important luthiers (i.e. guitarreros) of the first half of the twentieth century would be educated.

Francisco Tárrega, who lived up to the first years of the twentieth century, played on Torres’ guitars. Through his compositions and transcriptions, but even more through his pedagogical activity, he laid the foundations on which the modern guitar technique would take shape. This technique be transmitted by his most important students, both direct and indirect.

The Homenaje for guitar, written by Manuel de Falla in 1920 to pay homage to Claude Debussy’s death, would instead be the spark literally igniting, for the first time in guitar’s history, the interest of “non-guitarist” composers toward this instrument. Within an unbelievably short time, this would lead to the birth of a repertory exceptional in quantity and quality.

The project “Alma Guitarra” starts from here, and is centered on the rediscovery of the guitar’s authentic sound in those so fundamental years. Then, unbelievable talents in the fields of instrument-making, composition, and interpretation, led to such extraordinary results.

This research is directed toward the instrument’s deepest soul, and toward its unbelievable generating power, reaching present-day from the beginning of the twentieth century. The word “alma” takes here a double meaning. In Spanish, it means “soul”; in Latin, it derives from the verb alere, “to nourish, to give life”.

For this recording, I employed three guitars built between 1916 and 1942 by the greatest masters of instrument-making of the Madrid school, i.e. Manuel Ramírez and Santos Hernandez. The choice of these precious instruments was the direct consequence of my research. Each guitar was assigned to its repertoire, by degrees of timbral affinity and of similar character.

However, guitars without strings produce no sounds. It is precisely from the union between wood and the means putting it into vibration that the mysterious fascination of the guitar is born. The strings are therefore a fundamental part of the project. I used gut strings for the trebles, and strings of a particular synthetic silk wound for the basses. Up to approximately 1947, prior to the discovery of nylon and its use as the material for musical strings, the only material employed for the production of the guitar’s trebles had always been gut. Therefore, luthiers, composers, and especially performers grew up on the basis of this kind of string. It has its limits, mainly as concerns duration and reliability, but it has a colour and an expressivity which are very different with respect to modern nylon. For the basses, instead, a silk core was employed; here too, it would later by replaced by a flock of nylon. The sound of strings with a silk core is characterized by a much deeper, darker and less metallic sound with respect to the later strings with nylon core. This combination between strings and instruments leads not to homogeneity, therefore, but rather to an extreme timbral differentiation of the six strings. Each of them will then represent a different and perfectly recognizable voice of its own.

The repertory

It may seem unusual, at first sight, to find a Renaissance Fantasia, originally written for vihuela, at the beginning of an album focusing on the guitar repertoire of the Spanish twentieth century between the two Wars. Actually, in precisely those same years when this enormous mass of new repertoire was being created, the music written since the early sixteenth century was being rediscovered. These pieces were transcribed from ancient tablatures, and had been conceived for instruments such as the lute, the Baroque guitar and the vihuela de mano. This “new” music would represent a great stimulus for the guitarists and composers of the time.

Luys Milán has been one of the most important vihuelists. His only work, Libro de música de vihuela de mano intitulado el Maestro, published in Valencia in 1536, is the first written testimony of the vihuela repertoire to have been preserved. Milán’s music is highly original, and Fantasía X demonstrates this. It contains two typical traits of his writing: there are passages of consonancias (i.e. chords of simultaneous sounds, with few polyphonic elements) constantly alternating with redobles (quick ascending and descending scales with an improvisational character). They also demonstrate a very high level of development in the instrumental technique.

In the same region of Valencia was born also Joaquín Rodrigo. Among the non-guitarist composers, he certainly was the most deeply fascinated by this early repertoire. Indeed, his first work for solo guitar, written in 1926, i.e. his Zarabanda lejana (Distant Sarabanda), was subtitled as a “Homenaje a la vihuela de Luis Milán”. This influence can be found perhaps to an even higher degree in his Tiento Antiguo of 1942, following immediately Milán’s Fantasía in this album. The tiento is in fact an early musical form similar to the Toccata, employed by sixteenth-century vihuelists. I meant here to create a sort of diptych. En los Trigales (“In the wheat fields”), written in 1938, is instead a piece in a simple ABA form. The first section has a dancing character, and the second an intensely descriptive quality.

A composer from Madrid, Federico Moreno Torroba approached the guitar around the year 1920, prompted by the Andalusian guitarist Andrés Segovia, who at the time was 27 years old. Segovia was beginning, at that time, to explore the interest of composers who could write new works dedicated to him. The Danza castellana would later become, in 1926, the third and last movement of the Suite castellana, with the mere title of “Danza”. It is the first fruit born from this prolific cooperation. Even though Segovia always stated that this piece had been written by Moreno Torroba in 1919, recent studies demonstrated beyond any doubt that its composition date has to be postponed to the first months of 1921, or, at the limit, to December 1920 (i.e. after de Falla’s Homenaje). From the interpretive viewpoint. The Suite Castellana accompanied Segovia throughout his long and phenomenal concert activity. However, curiously, we have no discographic witness of his interpretation of the Danza. The Nocturno is a piece with an Impressionist inspiration. Here, stupendous timbral intuitions are joined with a more clearly “French” harmonic taste. The Burgalesa has been recorded here in its original key, F# major, rather than in the adaptation made by Segovia (in E major); it is a song inspired by the Castilian city of Burgos.

In Burgos was born, in 1896, Regino Sainz de la Maza. He was a guitarist, composer, and, since 1935, the first professor of guitar at the “Real Conservatorio Superior de Música” of Madrid. He was a pupil of Daniel Fortea, who had been in turn a student of Tárrega. Starting in the 1920s, he began an extraordinary career as a concert musician. Its summit was reached in 1940 when he premiered the famous Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra by Joaquín Rodrigo. He was also the dedicatee of this work. The premiere took place on a Santos Hernandez guitar in maple wood, similar to the one I use in this recording, with gut strings. Alirio Díaz, who had been his student at the Madrid Conservatory in the 1950s, remembered him as a sublime composer and a genius guitarist. Most of his works were published at a later date with respect to their composition. This can be deduced from the programs of his recitals and from some recordings. The pieces can therefore be dated back to the time I am taking into account, between the Twenties and the Forties. I recorded here his selection of arrangements after Castilian songs, as well as three pieces with an exquisitely Andalusian inspiration. These are the Rondeña (published in a preceding version with the title of Andaluza), a Petenera, and his very effectful version for solo guitar of the folksong El Vito.

By way of conclusion, in the fashion of a concert’s encore, and in order to remain within the Andalusian context, I added a version of my own after the famous Flamenco Rondeña written by the father of the modern Flamenco guitar, i.e. Ramón Montoya. This piece had been immortalized in a historical recording of 1936 on a Santos Hernandez guitar with – of course – gut strings.

The recording was realised in Sermoneta, in the 11th-century Church of St. Michael Archangel. No digital reverb has been added, in order to reproduce, at its best, the sound of these wonderful instruments, built by the knowledgeable hands of these great luthiers.

Marco Del Greco

![Henriette Eilertsen Trio - Moder (2026) [Hi-Res] Henriette Eilertsen Trio - Moder (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/13/shxstczqk3wm6d681pacpe28x.jpg)

![Sandro Fazio & Francesco Bearzatti - Dear Trane (2026) [Hi-Res] Sandro Fazio & Francesco Bearzatti - Dear Trane (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773145700_folder.jpg)