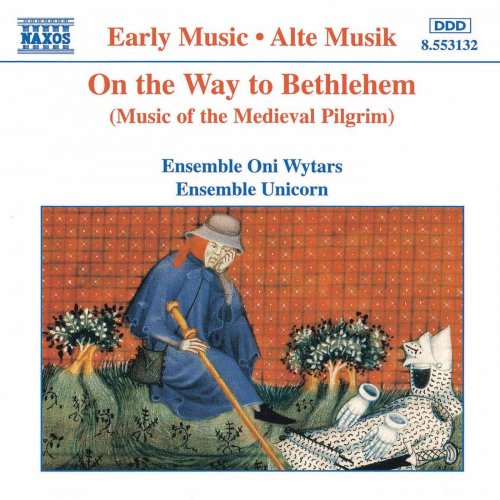

Ensemble Unicorn, Ensemble Oni Wytars - On the Way To Bethlehem: Music of the Medieval Pilgrim (1995)

Artist: Ensemble Unicorn, Ensemble Oni Wytars

Title: On the Way To Bethlehem: Music of the Medieval Pilgrim

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:12:56

Total Size: 332 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: On the Way To Bethlehem: Music of the Medieval Pilgrim

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 01:12:56

Total Size: 332 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Dinaresade

02. Edi be thu, Heven-Queene

03. Nevestinko oro

04. Beata progenies

05. Mari stanko

06. Sei willekommen Herre Christ

07. Bog se rodi va Betleme

08. Koleda na Bozic

09. Kod Betlehema

10. Koleda na Bozic

11. Angelus ad virginem

12. Düdül

13. Quinte Estampie real

14. Urbs Beata Ierusalem

15. Mevlâna

A traveller in the Middle Ages, whether pilgrim, crusader, messenger, cleric, student, beggar, merchant, king or Pope, was faced with dangers and difficulties along the road which we could barely imagine today. While this was especially true of journeys of some distance, into familiar territory, such travel was nevertheless common for a variety of reasons. We will concern ourselves here with travel to the Holy Land. For some people the journey was penance for a crime, others were motivated by deeply religious conviction, and still others were mainly interested in acquiring relics to bring home.

The relationship that developed between Europeans and non-Europeans through foreign commerce contributed greatly to the expansion of the travel routes. Trading in spices, perfumes, incense, narcotics and aphrodisiacs provided for centuries of contact between the Christian and the Islamic world. A negative aspect of this was the smugglers who sometimes disguised themselves as pilgrims. According to reports of the time, silkworm eggs were being smuggled from China to Jerusalem or, secret messages were hidden in pilgrim staffs. Because of this, anyone dressed as a pilgrim could be suspected of spying, subversion or dealing in contraband. So it was that Saint Coloman, while on a pilgrimage from England to the Holy Land, was hanged as a spy near Vienna.

While early pilgrimages, between the fourth and seventh centuries were thought of as a journey into penitence and solitude, or as a final destination in seeking a sanctified death, a radical change in philosophy took place when organized tours to the Holy Land, whatever Crusades or group pilgrimages, began. Now, rather than dying in the Holy Land, the lucky pilgrim who reached his goal was thought to be rewarded by God with earthly and heavenly riches, which he could then bring home. A pilgrimage no longer meant the end of one's life - it could even be repeated.

Maps were available for pilgrims. In extant maps of the Orient from the high Middle Ages, Jerusalem is pictured as the centre of the holy experience; the known continents of the time, Europe, Asia and Africa, are pictured surrounding it.

As early as the late fifteenth century, pilgrimages to the Holy Land, most by sea, were well-planned tours of differing class fares, with interpreters, tour guides, and phrasebooks, according to the 1484 travel report of the Canon of Mainze, Bernhard von Breydenbach. While these journeys eventually became routine, the ever-present obstacles of wheather, disease, robbery, etc., could not be overlooked: it was usual to expect a pilgrimage to take an entire year.

Especially complicated was the land route, opened up after the christianisation of Hungary around 1000 A.D., which led through Hungary, Croatia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Turkey and Syria on its way to Palestine. One was expected to carry "gifts" to appease the local authorities, who would detain a traveller along his way. Along this route travellers encountered cultures completely foreign to them, which had developed from and been influenced by a variety of unfamiliar styles and traditions.

Every pilgrim who wanted to return home safely needed to have some facility with Latin, Greek, and Arabic. In Eastern Europe he could get by with a mixture of rudimentary Hebrew and Aramaic, as well as with words from German, French (Franconian) and Italian dialects. Where words failed, sign languages, gestures and music helped. Musical talent was often useful in the search for food and lodging along the way, and was offered as thanks, as a symbol of gratitude and honour. Reports tell of a traveller who was a frequent or long-term guest in a place being given a parting dinner which included a complete musical programme. This is one of the ways that travellers came into contact with unknown and exotic musical practices.

About a century after the founding of Islam, Sufism was developed, spawning a new epoch of the classical Arabic school. The Sufi and Dervish orders believed that only those who understood "how to hear music" could experience higher truth through spiritual ecstasy.

Reports of people who died while in an ecstatic trance, inspired by listening to music, are not uncommon in Arabic literature. The music responsible for such rapture is based on a modal system using untempered intervals. Each melody has its own scale, pitch and range. A modern Mevlevi Orchestra is made up of singers and instrumentalists; flutes and drums accompany the dance of the Whirling Dervishes. The selections Dinarezade and Mevlana are examples of melodies that invite the listener to spend time with the music, enough to absorb and feel its full effect.

This recording offers a musical journey from England, the most western country and launching point of the first Crusade, through France, Germany, Eastern Europe, as far east as Syria. The musical selections from Europe are thematically Christmas art-songs; the selections from the Balkans and the Near East are traditional, meaning, with the exception of the Sufi music, that it is popular music, rather than art music. As is usual with popular music, the melodies were not, or were only partially, notated. Information about performance practice is obtained only from secondary sources, such as travel reports and iconography. This music was orally transmitted, slowly changing over generations, before it was, only recently, written down, within the last few centuries. It is therefore not surprising to encounter different versions of the same piece of music. The instruments played on this recording correspond to those known to have been used between 1200 and 1500. It is interesting to note that many traditional instruments of the Orient, such as the oud, kaval, gaida, chalumeau and various percussion instruments, remain virtually unchanged and continue to be used in traditional music today.

![Jesper Thörn - Stille (2026) [Hi-Res] Jesper Thörn - Stille (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769692710_p5yy87fosszfb_600.jpg)

![Santana - Borboletta (1974/2024) [SACD] Santana - Borboletta (1974/2024) [SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769789656_front.jpg)

![Putumayo - French Bossa Nova by Putumayo (2026) [Hi-Res] Putumayo - French Bossa Nova by Putumayo (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769675125_a0958635985_10.jpg)

![Vesna Pisarovic - Poravna (2025) [Hi-Res] Vesna Pisarovic - Poravna (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770024886_xcr9mudmw50b1it2dr9qpqkv0.jpg)

![Airelle Besson & Lionel Suarez - Blossom (2026) [Hi-Res] Airelle Besson & Lionel Suarez - Blossom (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769597029_lfh22npxya1ic_600.jpg)

![Billie Holiday - All Or Nothing At All (2025 Mono Remaster) (2026) [Hi-Res] Billie Holiday - All Or Nothing At All (2025 Mono Remaster) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769782333_cover.jpg)