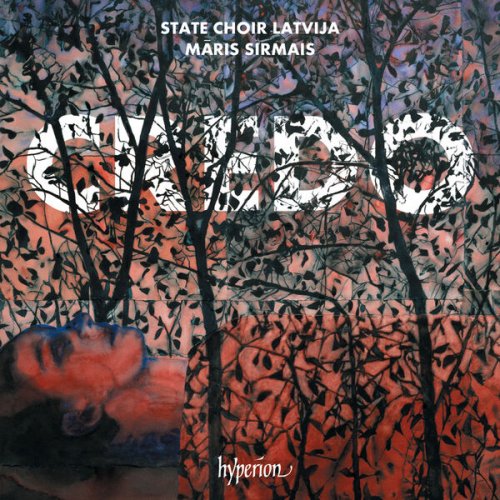

State Choir Latvija, Maris Sirmais - Credo (2023) [Hi-Res]

Artist: State Choir Latvija, Maris Sirmais

Title: Credo

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz +Booklet

Total Time: 00:55:58

Total Size: 263 / 963 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Credo

Year Of Release: 2023

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz +Booklet

Total Time: 00:55:58

Total Size: 263 / 963 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Deutsche Motette, Op. 62

02. 4 Songs of Love: No. 1, Let Him Kiss Me

03. 4 Songs of Love: No. 2, Until the Daybreak

04. 4 Songs of Love: No. 3, Awake, O North Wind

05. 4 Songs of Love: No. 4, His Left Hand

06. Louange à l'éternité de Jésus (Arr. Gottwald for Choir)

07. He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven

08. Der Abend, Op. 34 No. 1

09. Credo / I Believe

This exhortation appears in the first chapter of Olivier Messiaen’s short book The technique of my musical language (Leduc, Paris, 1944; English translation by John Satterfield). Arising in a preamble to Messiaen’s detailed exposition of his own methods, the quoted remark has a more universal resonance, acknowledging as it does the perennial sifting through which composers of all generations selectively harness, adapt or reject time-honoured principles formerly seen as axiomatic.

A key aspect of this sifting process is the handling of dissonant harmonies within a wider vocabulary of chords. In the sixteenth century, despite many creative instances of rule-bending, composers generally observed the principle that a dissonance was subject to a tripartite process of preparation (planting the dissonant note in readiness), suspension (moving the rest of the harmony against the dissonant note) and resolution (moving the dissonant note, usually downwards, to rehabilitate it within a consonant chord). This is what lent to sixteenth-century polyphony its tidal quality of rising tension followed by ebbing release.

Fast-forward to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and the relative proliferation of dissonant harmonies has thrown into question the fundamental notion of what is dissonant and what is consonant. While it remains possible to adopt the sixteenth century’s tripartite process of preparation–suspension–resolution, the dogmatic necessity to do so has largely evaporated, as the listening ear has adjusted itself to perceive euphonious harmony in chords once considered egregiously rule-breaking. A take-it-or-leave-it approach has arisen. While we can still detect Messiaen’s ‘upholding of the old rules’, the ways in which they may be ‘observed, augmented or added to with things still older’ have become too many and too varied to classify. Counterpoint comes and goes; tectonic plates may shift, allowing one densely massed chord to emerge out of the shadow of another like a photographic image going in and out of focus. The tidal sense of escalating and ebbing tension is sometimes hard to discern, or else replaced by complete harmonic stasis. Often the composer’s informing genetic memory is not of choral forces singing sixteenth-century textures, but of the more recent evolution of the symphony orchestra and the textures of which it is capable, with foreground gesture and detail often playing transiently across the surface of a static or slower-moving harmonic backdrop. ‘Orchestrating’ is no longer confined to the orchestra: instead, a composer such as Richard Strauss may mix and match the permutations of unison doubling between two or more choral parts, simply in the interests of allowing one strand in the texture more prominence than the others. The extremities of pitch required of singers increase significantly, ranging from subterranean depths to stratospheric heights. With this comes the possibility of expanding the common chord across more octaves, as if the performers were not singers but the woodwind or brass section of an orchestra.

These characteristics are all apparent in the eclectic yet intriguingly unified programme presented here by the State Choir Latvija.

Richard Strauss completed his Deutsche Motette on 22 June 1913 at his villa in the Bavarian Alpine resort town of Garmisch. His fame had been cemented in December 1905 by the opera Salome, a succès de scandale if ever there was one, the proceeds from which had enabled the composer to build his home. The further opera Der Rosenkavalier had been scarcely less successful at its Dresden premiere in January 1911, receiving London and New York premieres in January and December 1913 respectively. Meanwhile, Ariadne auf Naxos had been performed in Stuttgart in October 1912. The Deutsche Motette coincided with work on Eine Alpensinfonie, conceived for a massive orchestra and achieving what the late Michael Kennedy aptly described as ‘a Brucknerian evocation of the grandeur of the Alps’ (visible from Strauss’s home). It is therefore perhaps no surprise that the majestic spirit of Bruckner’s sacred choral music seems to inform the Motette, whose dense chordal agglomerations feel like an extension of orchestral thinking.

For his text, Strauss chose an untitled poem from Weihestunden (‘Hours of consecration’) in the volume Hymnen (‘Hymns’) by Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866). Rückert has tended to be rather dismissively regarded in literary circles and worked primarily as professor of oriental languages (allegedly master of thirty of them) at the Universities of Erlangen and Berlin. However, his importance to composers is evident in the list of those who set his verse; this includes Schubert, Robert and Clara Schumann, Brahms, Bruch, Wolf, Mahler, Zemlinsky and a host of others.

Scored for dauntingly extravagant forces, the Deutsche Motette opens in subdued hymn-like fashion, but soon sends its soprano and tenor soloists to stratospheric heights of pitch. The music reaches a radiant first climax in the key of E flat. A recurrent feature of the texture is the manner in which the soloists project more mobile motifs across a relatively static choral surface; but the stasis is offset by continual pivot notes or chords that send the harmony elliptically into unexpected territory. The rhythmic character of the music becomes more diverse and more animated with the words ‘O lass im feuchten Hauch … Nicht sprossen’ before breaking into flowing triplets. ‘O zeig’ mir, mich zu erquicken’ launches a lengthy passage of elaborate fugal writing in which the music migrates freely between sostenuto long lines and the feeling of a processional march. The fugal subject dominates the rest of the work and one senses the legacy of the Alpensinfonie as the surmounting of each sonic peak opens up a fresh vista of the next. Sending the lowest basses to subterranean depths and the soprano soloist to the uppermost limits of her register, Strauss conjures seemingly limitless vertical spaces in a sustained epilogue that recalls such perorations as the ending of his tone poem Tod und Verklärung (‘Death and transfiguration’, 1888-89).

Der Abend sets a text by Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805) for forces no less opulent than those of the Deutsche Motette. Within the composer’s Opus 34 it is paired with an earlier setting of another poem by Rückert. Broadly similar to the Motette in rhythmic character and texture, Der Abend opens with hymn-like chordal textures unfolding beneath a sustained high G which persists throughout the first twenty bars by being passed between the four soprano parts. A brief climax leads to one of Strauss’s trademark sidelong shifts of tonality, into B flat major, and triplet figures enliven the surface of the music in its middle stages, evoking the sun setting over a calm sea. Despite passages of rhapsodically imitative polyphony, the informing approach is often that of Strauss the orchestrator, with multiple unison doublings used to reinforce salient melodic lines. The music rediscovers its initial G major tonality before eventually finding safe harbour in a tranquil E major conclusion.

The Swedish composer Sven-David Sandström studied musicology and history of art at the University of Stockholm, and composition at the Royal College of Music in the same city. His output embraces concertos for flute, guitar, piano and cello, ballets, chamber music and the opera Jeppe: The cruel comedy. His music integrates ideas drawn from pop music, jazz and minimalism, and he was active also as a film composer. Having started out as one of Sweden’s foremost modernists, during the 1980s he turned towards postmodernism, cultivating a simpler, less astringent musical language. The Four songs of love exemplify this. Setting selected verses in English from the Biblical Song of Songs (otherwise Song of Solomon), these four brief pieces explore predominantly homophonic textures, often overlaying static or slow-moving façades of harmony with quicker verbal fragments. Let him kiss me begins with soprano, mezzo-soprano and alto parts punctuated by wordless tenor, baritone and bass, before the text is passed downwards to these lower voices. The tenor line soon soars into the upper extremes of its range. Parts freely divide into two in a fashion dictated by vertically thinking ‘orchestration’ of the harmonies rather than the contours of linear voice-leading. The setting hovers inconclusively between the related triadic areas of G minor and E flat major, beginning with the former and ending with the latter.

Until the daybreak presents the text of the title at two speeds, with transient upper voices playing across the sustained surface of lower chords, before a short-lived climax on the words ‘… and the shadows flee away’. In the latter stages the tonal G–E flat relationship of the previous song is reprised, before being carried over into the third, Awake, O north wind, whose opening fans upward from the bass regions in a kind of musical ‘Mexican wave’. Rapid syllabic articulation is belied by unwavering pitch and harmony, conveying a sense of events moving both quickly and slowly at the same time. With the phrase ‘Let my beloved come into his garden’ the tumult is stilled and the music gradually subsides towards a hushed, evanescent ending in the remote tonality of A minor. From that key the final song His left hand emerges, dividing verbal continuity between the alternating upper and lower halves of the chorus. Extending for a mere twenty bars and initially referring back to Until the daybreak, this enigmatic movement counterpoints harmonic procedures from the nineteenth century with dissonances that step like shadows from behind familiar consonant chords, creating a sonic halo around the inner core of the harmony. This effect is reversed when the final, beatific F major chord crystallizes from a dissonant nebula of extraneous pitches.

Messiaen wrote his Quatuor pour la fin du Temps at Stalag VIII-A, a POW camp roughly seventy miles east of the German city of Dresden. Here it was first performed on 15 January 1941 before an audience of just over 400. Although the work is for violin, clarinet, cello and piano, its fifth movement, Louange à l’éternité de Jésus (‘Praise to the eternity of Jesus’), requires only the last two of these instruments. At once monolithic and hypnotically sculptural in its effect, this timeless unfolding meditates on the idea of Christ as the embodiment of the Word of God. It consists of a sustained cello cantilena against piano chords which arrest the attention not merely by deviating continually from any expected tonal and harmonic direction, but also by being unguessably inconsistent in the number of their respective repetitions. Opening with a monody for cello alone, the music begins (with the piano entry) and ends on a chord of E major, yet projects this tonality as a kind of perpetual fulcrum, not a point of definitive arrival. In the central stages of the movement the piano becomes increasingly clangorous, while the cello seldom moves outside its middle and upper registers, preserving a rapt tonal intensity throughout. While the emotional atmosphere of such music might lend itself in principle to choral adaptation, on the face of it a foregrounded solo thread against a harmonic backdrop of repeating chords presents formidable obstacles for the arranger—especially when the composer’s tempo marking at the start is a daunting ‘Infiniment lent’ …

![Dorothy Donegan - World Recording Sessions 1944/45 (Mono Remastered) (2025) [Hi-Res] Dorothy Donegan - World Recording Sessions 1944/45 (Mono Remastered) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766499237_folder.jpg)