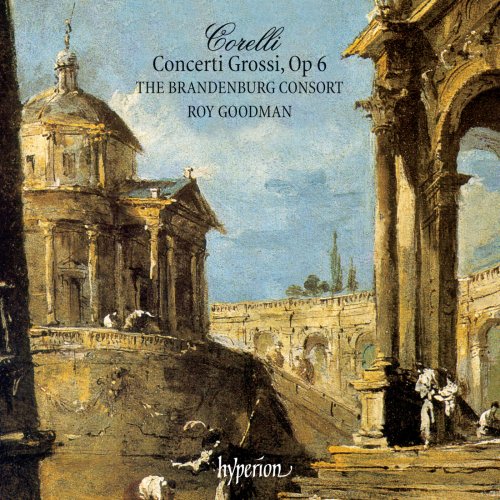

The Brandenburg Consort, Roy Goodman - Corelli: 12 Concerti Grossi, Op. 6 (1993)

Artist: The Brandenburg Consort, Roy Goodman

Title: Corelli: 12 Concerti Grossi, Op. 6

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 02:18:09

Total Size: 705 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Corelli: 12 Concerti Grossi, Op. 6

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 02:18:09

Total Size: 705 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD1

01. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: I. Largo – Allegro

02. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: II. Largo

03. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: III. Allegro

04. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: IV. Largo

05. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: V. Allegro

06. Concerto grosso No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6/1: VI. Allegro

07. Concerto grosso No. 2 in F Major, Op. 6/2: I. Vivace

08. Concerto grosso No. 2 in F Major, Op. 6/2: II. Allegro

09. Concerto grosso No. 2 in F Major, Op. 6/2: III. Grave – Andante largo

10. Concerto grosso No. 2 in F Major, Op. 6/2: IV. Allegro

11. Concerto grosso No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 6/3: I. Largo

12. Concerto grosso No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 6/3: II. Allegro

13. Concerto grosso No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 6/3: III. Grave

14. Concerto grosso No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 6/3: IV. Vivace

15. Concerto grosso No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 6/3: V. Allegro

16. Concerto grosso No. 4 in D Major, Op. 6/4: I. Adagio – Allegro

17. Concerto grosso No. 4 in D Major, Op. 6/4: II. Adagio

18. Concerto grosso No. 4 in D Major, Op. 6/4: III. Vivace

19. Concerto grosso No. 4 in D Major, Op. 6/4: IV. Allegro

20. Concerto grosso No. 4 in D Major, Op. 6/4: IVb. Allegro

21. Concerto grosso in B-Flat Major, Op. 6 No. 5: I. Adagio – Allegro

22. Concerto grosso in B-Flat Major, Op. 6 No. 5: II. Adagio

23. Concerto grosso in B-Flat Major, Op. 6 No. 5: III. Allegro

24. Concerto grosso in B-Flat Major, Op. 6 No. 5: IV. Largo

25. Concerto grosso in B-Flat Major, Op. 6 No. 5: V. Allegro

26. Concerto grosso No. 6 in F Major, Op. 6/6: I. Adagio

27. Concerto grosso No. 6 in F Major, Op. 6/6: II. Allegro

28. Concerto grosso No. 6 in F Major, Op. 6/6: III. Largo

29. Concerto grosso No. 6 in F Major, Op. 6/6: IV. Vivace

30. Concerto grosso No. 6 in F Major, Op. 6/6: V. Allegro

CD2

01. Concerto grosso No. 7 in D Major, Op. 6/7: I. Vivace – Allegro

02. Concerto grosso No. 7 in D Major, Op. 6/7: II. Allegro

03. Concerto grosso No. 7 in D Major, Op. 6/7: III. Andante largo

04. Concerto grosso No. 7 in D Major, Op. 6/7: IV. Allegro

05. Concerto grosso No. 7 in D Major, Op. 6/7: V. Vivace

06. Concerto grosso No. 8 in G Minor, Op. 6/8 "Christmas Concerto": I. Vivace – Grave

07. Concerto grosso in G Minor, Op. 6 No. 8 "Christmas Concerto": II. Allegro

08. Concerto grosso No. 8 in G Minor, Op. 6/8 "Christmas Concerto": III. Adagio – Allegro – Adagio

09. Concerto grosso No. 8 in G Minor, Op. 6/8 "Christmas Concerto": IV. Vivace

10. Concerto grosso No. 8 in G Minor, Op. 6/8 "Christmas Concerto": V. Allegro

11. Concerto grosso No. 8 in G Minor, Op. 6/8 "Christmas Concerto": VI. Largo. Pastorale

12. Concerto grosso No. 9 in F Major, Op. 6/9: I. Preludio. Largo

13. Concerto grosso No. 9 in F Major, Op. 6/9: II. Allemanda. Allegro

14. Concerto grosso No. 9 in F Major, Op. 6/9: III. Corrente. Vivace

15. Concerto grosso No. 9 in F Major, Op. 6/9: IV. Gavotta. Allegro

16. Concerto grosso No. 9 in F Major, Op. 6/9: V. Adagio

18. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: I. Preludio. Andante largo

19. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: II. Allemanda. Allegro

20. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: III. Adagio

21. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: IV. Corrente. Vivace

22. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: V. Allegro

23. Concerto grosso No. 10 in C Major, Op. 6/10: VI. Minuetto. Vivace

24. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: I. Preludio. Andante largo

25. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: II. Allemanda. Allegro

26. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: III. Adagio

27. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: IV. Andante largo

28. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: V. Sarabanda. Largo

29. Concerto grosso No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 6/11: VI. Giga. Vivace

30. Concerto grosso No. 12 in F Major, Op. 6/12: I. Preludio. Adagio

31. Concerto grosso No. 12 in F Major, Op. 6/12: II. Allegro

32. Concerto grosso No. 12 in F Major, Op. 6/12: III. Adagio

33. Concerto grosso No. 12 in F Major, Op. 6/12: IV. Sarabanda. Vivace

34. Concerto grosso No. 12 in F Major, Op. 6/12: V. Giga. Allegro

Les vingt-quatre violons du Roi—the orchestra established at the court of Versailles under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687)—set a standard of orchestral discipline and instrumental technique which became the envy of seventeenth-century Europe. In 1663 the ten-year-old Georg Muffat went to Paris to study with Lully and in the prefaces to his two sets of suites Florilegium I & II (published 1695/8) and his Concerti Grossi (1701) he described Lully’s style and the different ways of playing dance music, providing a substantial treatise on bowing, ornamentation and orchestral disposition. Muffat also included many valuable comparisons and observations from his experiences in Italy, since, in the early 1680s, he studied in Rome with both Bernardo Pasquini and Arcangelo Corelli.

Muffat tells us that he heard Corelli performing concerti grossi in Rome ‘with the greatest exactitude by a large number of players’ and he also performed some of his own music in Corelli’s house. There was, without doubt, a fruitful exchange of ideas between the two composers and on his return to Salzburg in 1682, Muffat published his five string sonatas Armonico tributo which display many of the musical facets which we now describe as ‘Corellian’. Although they are scored for five-part string ensemble and owe much to the French style in the dance movements, the slow movements display all the characteristics of the two typical ‘Corellian’ models—one with a succession of homophonic chords, often short and isolated and prompting some embellishments, and the other with chains of ecstatic suspensions intertwined above a walking bass line. Both composers adopted a multi-movement structure (as many as seven) and share several features in the fast movements—running basses, rapid contrasts between solo and tutti and some lively contrapuntal writing. Since Muffat’s Armonico tributo was published thirty-four years before Corelli’s Concertos, then either the composition of Corelli’s work was very much earlier (we know that he composed a Christmas Concerto as early as 1690 for Cardinal Ottoboni) or Muffat had significantly more influence on Corelli than we might have previously thought. (The only recording of Muffat’s Armonico tributo can be heard on Helios CDH55191.)

By coincidence, Corelli and Muffat were both born in 1653, and it is easily forgotten that this was thirty-two years before Bach and Handel and, even more surprisingly, six years before Purcell. Corelli was born into a prosperous family of landowners, between Bologna and Ravenna, although unfortunately his father had died one month earlier. In 1666 he went to study the violin in Bologna—a city boasting a flourishing musical tradition at the great basilica of San Petronio—and he was admitted to the Academia Filarmonica four years later. By 1675 Corelli had joined the ranks of the numerous violinists in Rome (his name appears in account books as ‘Arcangelo Bolognese’) working his way upwards, as we can see from numerous documented performances, until entering the service of Queen Christina of Sweden as a chamber musician in 1679 (and to whom he dedicated his first set of twelve Trio Sonatas Opus 1 in 1681). The following year Corelli appeared as leader of ten violins at the church of S. Luigi, playing with his favourite pupil and lifelong friend Matteo Fornari, who was to remain as Corelli’s solo partner for many years. The solo cellist in Corelli’s ensemble was Giovanni Lorenzo Lulier from Spain and, judging by the many virtuosic passages for cello in these concertos, he obviously possessed a considerable technique.

Corelli eventually bequeathed all his violins and manuscripts to Fornari, as well as the engraved plates for this set of Concerti Grossi which had not been published before his death. Fornari dedicated them to the Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm and had them published by Estienne Roger of Amsterdam in 1714. For several years after Corelli’s death they were performed in the Pantheon on his anniversary and during the course of the eighteenth century they were printed in their original form in no fewer than eleven editions in Amsterdam, London and Paris and in twelve further arrangements ranging from two recorders and continuo to solo fortepiano! It is extraordinary that Corelli’s lasting reputation rests on just six published sets, this being the last. In addition there are four sets of twelve Trio Sonatas, and the magnificent set of twelve Violin Sonatas (also available on Hyperion CDD22047). This latter set, Opus 5, was probably the most popular of all time, since by 1800 there were already at least forty-two printed editions. Nevertheless, it is likely that Corelli composed much more in manuscript (a handful of ten works without opus number have survived and are listed in the complete catalogue of Hans Joachim Marx, 1980). Corelli is known to have been continually revising and perfecting his compositions and he probably only selected the very best for publication.

The twelve Concertos of Opus 6 are divided into two groups: Nos 1 to 8 are ‘da chiesa’ and therefore do not include any dance movements; Nos 9 to 12 are ‘da camera’ and include the four standard suite dances—Allemanda, Corrente, Sarabanda and Giga—as well as Gavotta and Minuetto. The solo writing is always for two violins, cello and continuo (in this recording we alternate between archlute, harpsichord and organ). The tutti parts are scored for conventional four-part strings and are technically very simple. In fact the solo violin parts only venture beyond third position once or twice—for example in the extended first movement of Concerto No 2 and the Vivace of Concerto No 6. It appears that Corelli himself had limitations with certain aspects of violin technique: having agreed to lead an orchestra in an opera for Scarlatti, he apparently had difficulty in playing a high passage which the Neapolitans managed easily and furthermore disgraced himself by making two false starts in C major to an aria in C minor! In 1707 he led an orchestra for Handel in both Il Trionfo del Tempo and La Resurrezione, the former none too successfully according to Hawkins. Nevertheless, his playing was also described as ‘learned, elegant and pathetic’ although one witness wrote that ‘it was usual for his countenance to be distorted, his eyes to become as red as fire and his eyeballs to roll as if in agony’.

Corelli is known to have played beautiful embellishments in his performances and we have used various sources as guidance in this recording. We have also paid particular attention to contemporary bowing styles (Corelli is known to have insisted on unanimity of bowing much as Lully had done—perhaps more advice from Muffat?) and seventeenth-century evidence with regard to tempi and phrasing. The typical size of a string orchestra in Rome can be seen from that directed by Corelli at S. Marcello in 1690, consisting of six violins, two violas, two cellos, two double basses, harpsichord and organ; the use of one or more archlutes was also very common. We have used slightly more violins and violas on this recording, although far fewer than the ‘gala’ size Corelli had at his disposal on various festive occasions.

The popularity of Corelli’s Concertos has never faded and it has been further supported by innumerable imitations and tributes from Ravenscroft, Geminiani and Couperin to Sir Michael Tippett. They have always been popular with performers (both amateur and professional) and especially in England where they continued to be played, and preferred even to those of Handel, until well into the nineteenth century. In 1789 Charles Burney wrote: ‘The concertos of Corelli seem to have withstood all the attacks of time and fashion … and the effect of the whole … [is] so majestic, solemn and sublime that they preclude all criticism.’

![Criolo, Amaro Freitas, Dino D'Santiago - CRIOLO, AMARO E DINO (2026) [Hi-Res] Criolo, Amaro Freitas, Dino D'Santiago - CRIOLO, AMARO E DINO (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/17/usrf0slui6mhit9yit6clcqw9.jpg)

![Billy Martin, Matt Glassmeyer, Jonathan Goldberger - State Fête (2026) [Hi-Res] Billy Martin, Matt Glassmeyer, Jonathan Goldberger - State Fête (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/17/u0qd21dtfeg13eogj3a9ybwsz.jpg)