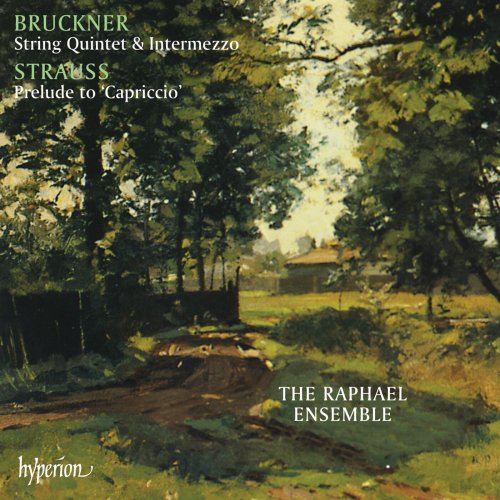

Raphael Ensemble - Bruckner: String Quintet - Strauss: Capriccio Prelude (1994)

Artist: Raphael Ensemble

Title: Bruckner: String Quintet - Strauss: Capriccio Prelude

Year Of Release: 1994

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:57:37

Total Size: 294 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Bruckner: String Quintet - Strauss: Capriccio Prelude

Year Of Release: 1994

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

Total Time: 00:57:37

Total Size: 294 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Capriccio, Op. 85: Introduction (Sextet)

02. String Quintet in F Major, WAB 112: I. Gemässigt

03. String Quintet in F Major, WAB 112: II. Scherzo. Schnell – Trio. Langsamer

04. String Quintet in F Major, WAB 112: III. Adagio

05. String Quintet in F Major, WAB 112: IV. Finale. Lebhaft bewegt

06. Intermezzo in D Minor for String Quintet, WAB 113

Richard Strauss’s last stage work is something of a curiosity. It has no action, no development, almost no plot, and none of the intricate characterization of the earlier operas. Capriccio is described as a ‘conversation piece for music in one act’. It was something of a self-indulgence for the ageing Strauss—a long consideration of the relative merit of words and music, a subject to which composers since Monteverdi had given much time and thought. Capriccio was written during 1940/41, to a libretto by Strauss’s friend the conductor Clemens Krauss, and first performed in Munich in October 1942, though the Sextet had been given privately some months before.

Strauss devises a play-within-a-play and sets the opera in a pre-Revolution French château. At the start, the Sextet is heard off-stage: it opens a concert devised by the composer Flamand for the birthday of the Countess Madeleine. Flamand and the poet Olivier respectively personify music and poetry; both seek the approval and love of the Countess and both watch for her reaction to this pure music.

As an independent piece, the Sextet is a welcome supplement to the meagre string sextet repertoire; by using two violins, two violas and two cellos Strauss acknowledges the Sextets of Brahms, whose chamber music he had loved since his student days. The thematic material of this prelude is later recalled in an orchestral interlude before the final scene, and again as the countess confronts her own reflection in a mirror and concludes that there is no answer to her questions and musings, and that words and music have equal merit.

A glance through the catalogue of the works of Anton Bruckner reminds us of his musical upbringing and environment: choral conductor, organist, then—having heard the music of Wagner—symphonist. His early works include music for military band and for orchestra, though their harmonic conception is firmly rooted in the organ loft. Of his very few pieces of chamber music, an early string quartet was written as a student exercise for a cellist with the Linz Municipal Theatre from whom Bruckner had taken lessons in composition. It remained undiscovered until long after the composer’s death. Some time after its composition, the violinist Joseph Hellmesberger asked Bruckner to write a work for his string quartet. It was not until seventeen years later that Bruckner planned a string quintet using Mozart’s scheme of quartet with an extra viola.

The Quintet was begun in December 1878, shortly after revisions to the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies. Bruckner was fifty-four. It was finished in July 1879 and shown to Hellmesberger. He was ‘not impressed’ with the Scherzo and refused to play the work, saying it was too difficult. Bruckner, ever compliant and anxious to please, wrote an Intermezzo which was completed several months later. The first performances were given without the Finale—in Cologne in December 1879 by the Heckmann Quartet, and by the Winkler Quartet in Vienna the following November. The Winkler Quartet was led by Josef Schalk and the second viola was played by his brother Franz, who (though a friend and admirer of Bruckner) was later to wreak such havoc on the Fifth Symphony by making inartistic cuts and adding music of his own. In May 1883 the Winkler Quartet gave the first complete performance with the original Scherzo and the Finale. Hellmesberger’s quartet finally played it (Scherzo and all) in May 1885.

What of the Quintet’s subsequent history? It was published in 1884 by Albert Gutmann and dedicated to Duke Max Emanuel of Bavaria. The Duke sent a diamond tie-pin in return; Bruckner received nothing from his publisher. The Quintet had over twenty public performances in Bruckner’s lifetime, and though it remains something of a curiosity in his total output it has a respectable reputation in the chamber repertoire and is unfamiliar to audiences merely because of its scoring and relatively unspectacular part-writing.

The first movement is arguably the most appropriate to the chamber music medium. It has the ‘feel’ of a chamber work, with intricate, leaping counterpoint and chromatic figures that would be lost in an orchestral texture. There are three distinct thematic strands—a broad melody heard at the outset, a dotted figure which is passed between various instruments, and a soft curving melody. Short rhythmic motifs abound in the exposition, which ends quietly after a climax in F sharp; the development uses several of these short figures and the movement ends firmly in F major.

The Scherzo has been described as both grotesque and endearing. Its jaunty D minor theme has the pulse of a country dance, though the modulations and wide leaps are redolent of a more intimate, sophisticated medium than that of the village band. The lyrical Trio is in E flat; it has a slower pulse, with a distinctive pizzicato accompaniment that recalls more symphonic writing.

It is difficult to see why Hellmesberger found this movement unacceptable—his players must have known the quartets of Beethoven, some of which have part-writing which is as technically and musically demanding as Bruckner’s Scherzo. A more likely reason for his antipathy to the work was his unwillingness to show public approval of Bruckner’s work which, privately, he admired.

The sublime Adagio is in G flat and forms the emotional centre of the whole work. Its effect is as profound as any of Beethoven’s late quartets or Bruckner’s own symphonic slow movements, and it is conceived on a similar scale. Indeed, the movement might easily be mistaken for a transcription of a symphonic slow movement, so confident is the handling of thematic material. There are three distinct episodes, and the movement ends in a mood of great peace and serenity.

In the Finale the string players battle with over-adventurous counterpoint and an orchestral texture. Bruckner appears to be writing a towering symphonic movement for solo strings, and the effect can easily sound strained and unconvincing. The movement begins in F minor with a second subject in E major, and a fugato development incorporates short motifs from the main thematic material. The recapitulation shows masterly use of the richness of the middle-heavy ensemble, and the Quintet ends briskly and sonorously in F major.

The Intermezzo has the same trio as the Scherzo which it originally replaced, and its genial directness conveys the mood of the Austrian Ländler. It has been even more neglected than the Quintet and there is no record of a public performance before 1904.

![Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res] Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/cn1c8l2hi7zp9j05a5u7nw49g.jpg)

![Barre Phillips - Three Day Moon (1978/2025) [Hi-Res] Barre Phillips - Three Day Moon (1978/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766322384_cover.jpg)

![Black Flower - Abyssinia Afterlife (2014) [Hi-Res] Black Flower - Abyssinia Afterlife (2014) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/anj3jk2va3pc3i9y3pv0m7zde.jpg)

![Santi Vega - Un Instante Infinito (2025) [Hi-Res] Santi Vega - Un Instante Infinito (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/19/xkxaonr6q5o8ydwyf3z1c8tp5.jpg)

![Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res] Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/snzv0mdiaf2dg21tiqrm87jaq.jpg)