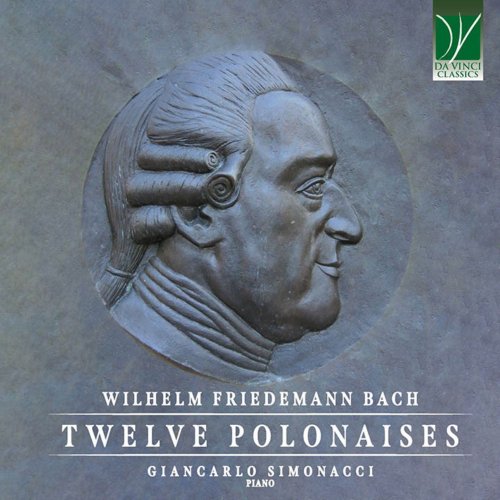

Giancarlo Simonacci - Twelve Polonaises (2024)

Artist: Giancarlo Simonacci

Title: Twelve Polonaises

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:58:35

Total Size: 158 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Twelve Polonaises

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:58:35

Total Size: 158 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. 12 Polonaises in C Major: I.

02. 12 Polonaises in C Minor: II.

03. 12 Polonaises in D Major: III.

04. 12 Polonaises in D Minor: IV.

05. 12 Polonaises in E-Flat Major: V.

06. 12 Polonaises in E-Flat Minor: VI.

07. 12 Polonaises in E Major: VII.

08. 12 Polonaises in E Minor: VIII.

09. 12 Polonaises in F Major: IX.

10. 12 Polonaises in F Minor: X.

11. 12 Polonaises in G Major: XI.

12. 12 Polonaises in G Minor: XII.

13. 4 Pieces in G Major

14. 4 Pieces in B Minor

15. 4 Pieces in D Minor

16. 4 Pieces in G Minor

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the firstborn of Johann Sebastian Bach’s numerous family, the son of his father’s first wife Maria Barbara. Wilhelm received his musical instruction from his father, who wrote for him a notebook called Clavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, and which bears immortal witness to Johann Sebastian’s pedagogical genius.

Wilhelm Friedemann grew into a successful musician, as a performer of many keyboard instruments, and as a celebrated and appreciated composer, even though his figure is somewhat paler than that of his two most famous brothers, Carl Philip Emanuel and Johann Christian. Even today, when the early music movement has unearthed many works by lesser-known composers, his output has not received the recognition it deserves.

This comparatively minor fortune may in part be attributed to the peculiar traits of this musician’s personality, which failed to endear him to his contemporaries in spite of his undeniable value. His character was somewhat edgy, and this led him to abandon some important jobs, including a post at the Dresden Church of St. Cecilia and at the Liebfrauenkirche of Halle, where he had also been appointed Director musices.

His difficulty in adapting himself to the requirement of a stable position led him, in the last years of his life, to earn his living as a freelance musician: this was the time when some pioneers among the musicians of the era decided to abandon the safety of a regular employment and to try their hand as independent artists (the most notable example is that of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart). However, both Mozart and Wilhelm Friedemann are also notable examples of how difficult that choice could be: both died in misery, and both left their surviving family almost destitute. In Wilhelm Friedemann’s case, his family consisted of two women: his wife Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi, whom he had married in 1751, and their daughter Friederike Sophie.

In spite of the possible shortcomings of his character, Wilhelm Friedemann was highly prized by his contemporaries, particularly as an improviser: seemingly, some thought him to be an even better improviser than his father, who is unanimously considered as one of the most skilled improvisers of all times. Furthermore, he left an output which is noteworthy both in qualitative and quantitative terms; in particular, his keyboard concertos are highly interesting and are considered as the direct antecedents of Mozart’s. His Concerto in F major for two harpsichords, written around 1773, is an absolute masterpiece. His oeuvre also includes sacred and secular cantatas, along with instrumental music such as symphonies and chamber music works (frequently called Sonatas). As a skilled keyboardist himself, unavoidably many of his compositions are for keyboard alone, among them Sonatas, Fantasias, Fugues and shorter works; notably, the Fantasias seem to record and offer a trace of that extraordinary improvisational powers which had earned him fame during his lifetime. His organ output is also worth knowing, and it includes a set of eight three-part fugues dedicated to Princess Anna Amalia of Prussia (1723-1787), who was in turn an amateur composer and had studied both the organ and the cello.

This Da Vinci Classics album includes Zwölf Polonaisen, written about 1765, which represent unmistakably one of the highpoints of Wilhelm Friedemann’s entire output. They were at least assembled, if not outright conceived, as a cycle; their tonal ordering seems to mirror the composer’s father’s interest in symmetry and completeness. While here, with just twelve pieces at his disposal, Wilhelm Friedemann could not aim at the same thoroughness found in Johann Sebastian’s Well-Tempered Clavier, still the pieces’ ordering seems to follow the same principle: the sequence, in fact, presents C major, C minor, D major, D minor, E-flat major, E-flat minor, E major, E minor, F major, F minor, G major and G minor. In order to achieve this sequence, Wilhelm Friedemann was forced to include some keys which were still very infrequently employed at his time (some of them, to be true, were used only sparsely also in the following centuries: most notably, E-flat minor). It is an open question whether Wilhelm Friedemann had intended the whole cycle of the twenty-four keys to be covered by his endeavour, or if he had meant to focus only on these first twelve keys purposefully.

The Polonaise was a court dance; it also came to symbolize nobility, majesty, and stateliness, particularly in the territories which were subject to the King of Poland. At Johann Sebastian and Wilhelm Friedemann’s times, however, the Polonaise had rather different qualities from those it would acquire with its most famous composer, i.e. Chopin, in the nineteenth century. One feature which remained typical and characteristic was the ternary time, along with the dactylic rhythm (i.e. one long note, which might be a quaver, followed by two notes with half the value of the preceding, e.g. semiquavers). In its being a symbol of refinement and solemnity, the Polonaise stood side by side with the dotted rhythm of French Overtures: in turn, it had acquired this symbolic value thanks to its association with the Roi Soleil and with his stately appearances in the Versailles theatre.

Wilhelm Friedemann’s Polonaises, however, are somewhat transfigured; they are certainly not intended as music to be actually danced, and, under this viewpoint, Wilhelm Friedemann saw eye to eye with his father, whose Suites, Partitas, and the likes are made of abstract dances, stylized gestures which transform the materiality of dance into a spiritual experience.

The pieces in the major mode are generally more flowing and briskly paced than their minor counterparts; at least, this is what is clearly discernible from the musical features of the pieces, since the composer abstains from adding tempo indications. (Though not as common as in later epochs, at Wilhelm Friedemann’s time many composers employed tempo indications rather profusely).

These works are normally short, written for two or three polyphonic parts. Their musical form is analogous to the classical Sonata Allegro form, though on a more concise and compact scale: there are two contrasting themes, a development and reprise.

Some of these Polonaises are worth presenting individually. For instance, the two works in C major and D major, whose pace is a brisk Allegro, have a rather similar compositional structure. The former, in C major, can be interpreted as a kind of refined Etude combining arpeggios and quick scales; technical proficiency is both expected and pursued through these pieces (just as some of Johann Sebastian’s Preludes from the Well-Tempered Clavier have a true Etude-like structure). Its D-major sibling, in conformity with many other pieces written in the same key, presents a fanfare-like, pompous, and solemn beginning. However, this is quickly followed by melismas, i.e. melodic, singing groups of notes, echoing vocal virtuosity. Both pieces seem to display a kind of agility which never fails to impress the listener.

By way of contrast, the G-major Polonaise is characterized by a light, elegant atmosphere of dancing, with a very refined writing and a high, luminous profile. It is somewhat reminiscent of a Minuet, although it is also oddly and eerily different from typical instances of that courtly dance.

The slower movements are among the highlights of the composer’s entire output, and are extraordinary pieces of touching beauty. The Adagio in E-flat minor (i.e. the key of one of Johann Sebastian’s most memorable and enchanting Preludes) is a beautiful example of the Empfindsamer Stil, the expressive style of the affections which characterized the Sturm-und-Drang era. It employs audacious, daring dissonances such as major seconds (and many others), resulting in a harmonic texture of extreme refinement, and in a musical atmosphere of veiled, opaque nostalgia.

The F-minor Adagio is in turn an unforgettable piece; it stands on equal footing with some of Johann Sebastian’s best Sarabandes, with their combination of expressivity, elegance, composure, and intensity. It displays a solemn, royal, stately pace; it digs deep into the possibilities granted by harmonic and melodic elaboration, resulting in an impressive, unforgettable moment of lyricism.

In the E-minor Adagio, the evocation of a singing style confers particular expressive intensity to the large intervals: this strategy was a landmark of Mozart’s style. In fact, singing large intervals (such as the initial tenth found here) is challenging for singers: those who manage to overcome this difficulty satisfactorily have a great expressive resource in their pockets. While the difficulty of playing an interval of tenth on a piano is by no means comparable with that of singing a tenth, the impression of difficulty, and of artistic virtuosity, is maintained. The opening leap, thus, seems to pave the way for a whole new world. This is truly an Aria in the fashion of Italian belcanto, with an undeniably singing style.

These are probably the most unforgettable moments of the whole cycle, but all pieces display a wonderful variety of subtle rhythmic, melodic, harmonic nuances. Wilhelm Friedemann creates a whole universe of meaningful and surprising panoramas; furthermore, the result seems to flow naturally from his pen, although this is the fruit not only of natural talent, but also of high compositional refinement and skill.

It can be said, therefore, that Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was a first-rate composer. His restless soul prompted him to create and design paths which are rich in resources and perspectives; they enlightened new ways for the music of future.