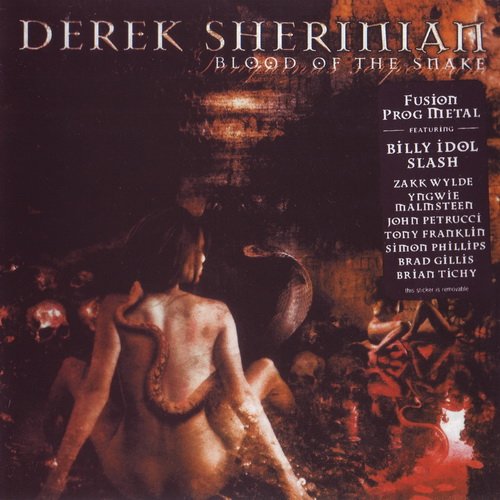

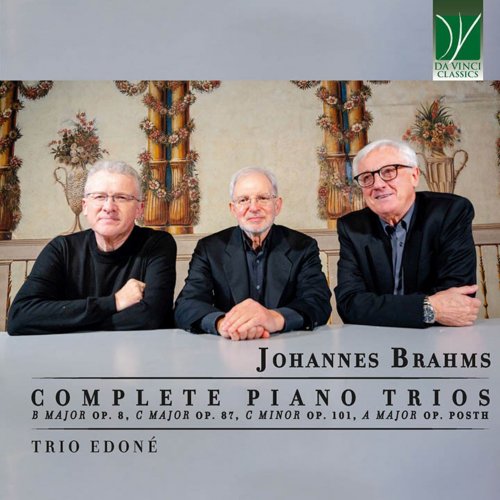

Paolo Ghidoni, Marco Perini, Ruggero Ruocco - Complete Piano Trios (2024)

Artist: Paolo Ghidoni, Marco Perini, Ruggero Ruocco

Title: Complete Piano Trios

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 02:10:42

Total Size: 610 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Complete Piano Trios

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 02:10:42

Total Size: 610 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD1

01. Piano Trio in B Major, Op. 8: I. Allegro con brio

02. Piano Trio in B Major, Op. 8: II. Scherzo. Allegro molto

03. Piano Trio in B Major, Op. 8: III. Adagio

04. Piano Trio in B Major, Op. 8: IV. Allegro

05. Piano Trio in C Major, Op. 87: I. Allegro

06. Piano Trio in C Major, Op. 87: II. Andante con moto

07. Piano Trio in C Major, Op. 87: III. Scherzo. Presto

08. Piano Trio in C Major, Op. 87: IV. Finale. Allegro giocoso

CD2

01. Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 101: I. Allegro energico

02. Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 101: II. Presto non assai

03. Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 101: III. Andante grazioso

04. Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 101: IV. Allegro molto

05. Piano Trio in A Major, Posth.: I. Moderato

06. Piano Trio in A Major, Posth.: II. Vivace

07. Piano Trio in A Major, Posth.: III. Lento

08. Piano Trio in A Major, Posth.: IV. Presto

The French speak of the malediction d’avoir bien fait, i.e. the curse of having done well. It indicates the uncomfortable situation of one who has accomplished something satisfactorily, and is therefore expected to be always up to the standard he or she has set. This may be a particularly daunting feeling especially for young people, whose creative powers may be paradoxically blocked precisely by the consciousness of a successful first exploit, and of the expectations this has caused.

A similar feeling may have arisen in young Johannes Brahms’ bosom, especially after the publication of Robert Schumann’s famous article Neue Bahnen (“New Ways”). Schumann was a splendid writer, and the editor-in-chief of the journal he had personally founded, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. And although he could be vitriolic in his outbursts, particularly against the “Philistines” of his time, he was much more eager to promote the colleagues he found worth supporting. Johannes Brahms, who had appeared on the Schumanns’ threshold as a twenty-year old young man, was certainly one of them; Schumann – whose mental health would be deteriorating soon afterwards – possibly saw in him the heir to his musicianship.

The article written by Schumann praised Brahms unconditionally and certainly created many expectations. Brahms was keenly aware of this. He wrote to Schumann that, given those expectations, he would be very careful in his selection of how to present himself to the public, especially in terms of which works to publish. He expressly mentioned that he was uninclined to send to the press “any of his Trios”, and this demonstrates that he had written more than one work in this genre prior to the publication of Neue Bahnen.

One of his youthful Trios, as a matter of fact, would eventually be published; indeed, not just once, but twice. Brahms’ Trio op. 8 had been written in Hannover in 1853-4, premiered in Danzig and soon afterwards at the Dodsworth Hall of New York; later, it would be played by Clara Schumann in Breslau. Published by Breitkopf & Härtel in this version, it would undergo major revisions in 1891, approximately thirty-five years later, when Simrock – who by then was Brahms’ major publisher – acquired the rights for his works that had been hitherto published by Breitkopf. This was the opportunity for Brahms to revise dramatically the Trio. He wrote to Clara Schumann: “You cannot imagine how I trifled away the lovely summer. I have rewritten my B-major Trio and can now call it op. 108 instead of op. 8. It will not be so dreary as before – but will it be better?”.

Elsewhere, he spoke of this operation with a similar kind of self-irony: he wrote to the conductor Julius Otto Grimm that he “was not going to put a wig on this wild man’s head, but comb his hair and tidy it up a bit”. In spite of these dismissive comments, the revision made by Brahms on his youthful work was to be deep and to involve all of its movements, as we will later see.

But what happened of the other Trio (or Trios)? In all likelihood, they went the way of many other works by Brahms, i.e. the fireplace. He was terribly self-critical and censored his own works with severity, as the letter to Schumann cited above demonstrates. Writing to Schumann, he asserted that he was going not to publish any of his trios not least for “not embarrassing” Schumann himself, who had exposed his public persona very much in promoting his young friend. And this was certainly a concern of young Brahms, who prized friendship as much as Schumann himself did. But also in later times, Brahms would keep revising his music and subtracting it from the press until and unless it was worth printing – in his own exacting eyes.

In our eyes, however, even a minor scrap of music from Brahms’ pen would be a treasure. It is understandable, therefore, that musicologists keep dreaming of finding a lost work by Brahms. In 1924, Ernst Bücken, a German scholar, received a stack of manuscripts coming from the estate of Dr Erich Preiger of Bonn (a collector who had also owned manuscripts of two Symphonies by Beethoven). Among these papers, he found a Piano Trio copied by an unknown hand, and without a title-page. The piece received its premiere in the following year, 1925, when it was presented as the work of “an as yet unknown composer”. Thirteen years later, in 1938 (a time when Germany was rather happy to boast its supremacy in whatever field), Bücken and Karl Hass edited the manuscript for publication by the press of Breitkopf & Härtel, and presented it as an op. posth. by Brahms. What makes the issue even thornier is that the original manuscript disappeared soon afterwards, never to be found again.

The attribution was made on purely musical grounds, and on the basis of comparison with the style of the op. 8 Trio, to which Bücken argued that the A-major Trio should be contemporaneous. Undeniably, there are many “Brahms-like” elements in this Trio, although none that can be nobody else’s: Brahms’ style was emulated by some of his students and disciples, and, for instance, Albert Dietrich, a friend of him, is a likely alternative in possible authorship. His candidacy has been championed by other scholars who challenged Bücken’s attribution; today, in the absence of any original sources, stylistic evidence is insufficient for either proving or disproving the attribution.

What is undeniable is that the A-major Trio recorded here is beautiful and very pleasing to listen to, with hints to, and reminiscences after, many great Romantic composers. The first movement, in the Sonata form, is built around the traditional couple of themes: the first is solemn and expressive, with luxuriant harmonies and modulations; the second is livelier and brisker. In the development, elements suggestive of gipsy atmospheres are found; this was a typical source of inspiration for Brahms, who was always fascinated by Hungarian and gipsy music, and whose first successes as a pianist came from his tours with a gipsy violinist. These elements are also to be found in the Scherzo and in the Finale of this Trio.

The Scherzo in fact follows the first movement, and it presents a kind of dark humour underpinned by a compelling rhythmical element; it frames the gentle Trio, with its touching melancholy and nostalgia.

The third movement, the lyrical centrepiece of the work, is full of poetry and imagination. Its slow pace punctuated by dotted rhythms evokes a funereal march, slightly reminiscent of Schubert’s E-flat major Trio and of Schumann’s Piano Quintet.

The Finale is the most enthralling of the four movements: written once more in the Sonata form, it displays reminiscences of many great composers, but is also genuine and spontaneous in its evocations of country dance and folk music. Fascinatingly, it also comprises suggestions of fugal writing and of the technique of variations, both of which are typical traits of Brahms’ mature style. Is it a lost work by Brahms, then? Impossible to say; but, forgetting for a while the typically modern obsession for authorship, one may simply enjoy this beautiful music which deserves to be listened to and cherished, whoever may have written it.

Although the B-major Trio is allegedly coeval with the A-major Trio, in its original form, the revisions it underwent make it a hybrid work, with elements from Brahms’ youthful style, but also with a perspective which clearly belongs to the adult composer. The revised version maintains the splendid opening theme of the first movement, which sounds as a Sonata for cello and piano, preserving the sound of the violin for a later appearance. Brahms, instead, changed substantially the second theme, replacing the original one with a pulsating second which makes a more powerful contrast with the first. The second movement, a Scherzo again, was left practically untouched by the revisions: probably, the ageing Brahms approved of the youthful enthusiasm pervading its vital energy, and found it fully satisfactory. It also demonstrates the ability of the young composer in the handling of counterpoint and polyphony.

Generally speaking, also the third movement was preserved in the main: the capacity of writing unforgettable melodies was of the young Brahms no less than of the mature composer. However, a new, touching wordless song for cello and piano is a welcome addition of the revised version.

The Finale is, unexpectedly, in the minor mode, and is also challenging from the tonal viewpoint, as it reveals its cards only at its end. Here too we find a powerful Hungarian inspiration; but what strikes the listener most is the somber darkness of its mood, possibly suggestive of the tragedy which was to hit the Schumann family and their friends soon afterwards.

What is officially known as his Second Trio was begun in 1880 and finished in 1882, at a time of important personal changes for Brahms (the most visible of which was the beard he grew). He was very satisfied with his work, and wrote to his publisher: “You have not yet had such a beautiful trio from me and very likely have not published its equal in the last ten years”. His ability in the construction of form is evident in the economy of the means he employs, deriving many thematic elements from the opening statement. Furthermore, this Trio can be understood almost as a piece for two pianos, one of which is made by the couple of bowed string instruments, which frequently tend to play the same melody in octaves. Typical Brahms is the frequent employ of displaced accents or metrical ambiguities. The second movement is a theme with variations, once again with Hungarian suggestions. In this Trio, the Scherzo is found in the third place, and once more the vivacity (though in a dark mood) of the A sections is enticingly contrasted with the enchantment of the B part. The Finale is a masterpiece also as concerns the treatment of form, which derives from known models but combines them creatively.

Finally, the C-minor Trio is the fruit of Brahms’ full maturity, and draws from the traditional forms he so cherished. Here too, much of the material for the first movement, and for most of the other movements, seems to spring from the motif found at the beginning. The second movement alludes to that motivic motto and to a rhythm also found in the first movement, and employs these few musical ideas as the source of a whirlwind of notes. The slow movement is an Andante grazioso (so not very slow), and once more it references the opening motto; it employs beautiful sonorities with pizzicatos and singing tunes. In the Finale, many of the elements cited above seem to converge, as if in a masked ball; in this movement in the sonata-form a kind of recapitulation is offered, which embraces and explains all that has happened during this piece’s performance.

Together, these four Trios offer to the listener a captivating experience and a thorough panorama over a variety of moods, musical intentions, and ideas, inviting their imagination to a wonderful Romantic itinerary.