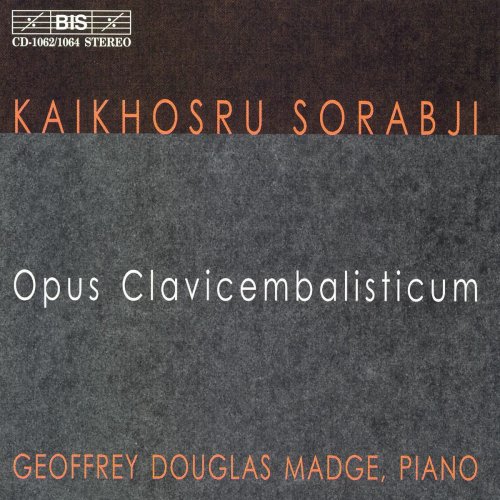

Geoffrey Douglas Madge - Kaikhosru Sorabji: Opus clavicembalisticum (2001)

Artist: Geoffrey Douglas Madge

Title: Kaikhosru Sorabji: Opus clavicembalisticum

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: BIS

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 03:59:08

Total Size: 1 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Kaikhosru Sorabji: Opus clavicembalisticum

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: BIS

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 03:59:08

Total Size: 1 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1

Pars Prima

1. I. Introito 3:03

2. II. Preludio-Corale (Nexus) 13:33

3. III. Fuga I Quatuor Vocibus 12:06

4. IV. Fantasia 5:35

5. V. Fuga II Duplex 15:30

CD 2

Pars Altera

1. VI. Interludium Primum (Thema Cum XLIX Variationibus) 44:44

2. VII. Candenza I 4:40

CD 3

VIII. Fuga Tertia Triplex (33:18)

1. Dux Primus 10:17

2. Dux Alter 11:01

3. Dux Tertius 12:00

CD 4

Part Tertia

IX. Interludium Alterum (57:17)

1. Toccata 5:42

2. Adagio 16:17

3. Passacaglia Cum LXXXI Variationibus 35:06

4. X. Cadenza II 3:04

CD 5

XI. Fuga IV Quadruplex (33:18)

1. Dux Primus 8:28

2. Dux Alter 7:32

3. Dux Tertius 7:23

4. Dux Quartus 9:57

5. XII. Coda-Stretta 7:30

6. Applause 1:22

Performers:

Geoffrey Douglas Madge, piano

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892 - 1988) disdained anything so vain or plebian as currency: accepting the challenge of the greatest because most dense and extended works in the western musical tradition - from Bach's "Art of the Fugue" and "Well Tempered Clavier" and from Beethoven's monumental "Diabelli Variations" - he sought to outdo the pattern-makers in creating massive compositions of a diabolically complex motivic and contrapuntal character, requiring, in order to work out their inner logic, performance-times to be calculated in hours. To set the seal on his elite conception of musical art, Sorabji largely forbade public recitals of his work, yielding on a few occasions only, guaranteeing that no helpful performance-traditions would arise. But how could it? When pianist John Ogdon played a public concert of "Opus Clavicembalisticum" in 1975, it took five hours. Kenneth Derus, who contributes the fine notes to Geoffrey Madge's 1982 Chicago concert of the same work, now available on a BIS boxed set, argues that Ogdon played too slowly, distending the score by a full hour. Even so, no pianist can play a four-hour piece as demanding as the "Opus" more than once or twice a year - presuming that an audience could be found to sit through the traversal. For listeners, the compact disc is the ideal medium for becoming acquainted (if that were possible) with Sorabji's monumental keyboard essay, although the composer might have balked, given that he insisted on playing the monster through from beginning to end. "Opus" is in three massive parts. "Pars Prima" consists of an "Introito" followed by a "Preludio-Corale," a Fugue (I) in four voices, a "Fantasia," and a Double Fugue (II). The sequence together needs fifty minutes or so, with the two fugues needing about a quarter of an hour each. "Pars Altera" consists of an "Interludium," really a set of sixty-nine variations on a theme, a "Cadenza" (I), and a gargantuan Triple Fugue (III). The variations need forty-five minutes and the Triple Fugue thirty-four. "Pars Tertia" consists of an "Interludium" (II) further subdivided into a Toccata, an Adagio, and a Passacaglia with eighty-one variations; now comes a "Cadenza" (II), after which there is a Quadruple Fugue (IV) and "Coda-Stretto." "Pars Tertia" needs an hour and forty-five minutes for its sequence to play out. What possible attraction is there in a solo piano work lasting so long? Can a listener hope to make sense of a Quadruple Fugue of forty minutes performance-duration? The answer is "no" and "yes." One can only just barely grasp the internal logic of one of Bach's longer fugues or one of Reger's. Sorabji creates imitative structures four or five times longer than those of either of these two precursor-composers. With Sorabji, one remembers that what one might call "something fugal" is unfolding before one's ears; and then one, so to speak, "identifies with it" by mystical intuitive union. Preparation is a "sine qua non" of the endeavor, for once interrupt the audition and the thread of sympathy is broken: one must set aside the requisite chunk of time, discharge one's other obligations, and then summon the spirits of endurance and concentration for all the assistance that they can give. The validity of Sorabji's accomplishment lies in the adequately prepared auditor's absolute conviction that "this is not a hoax" but a genuine "higher experience." "Opus Clavicembalisticum" belongs to the genre of vast works in appreciation of which a certain faith is the prior stipulation: Wagner's "Parsifal," Havergal Brian's "Gothic Symphony," Nicholas Maw's "Odyssey," Morton Feldman's "String Quartet (II)," or Alexander Nemtin's completion of Alexander Scriabin's "Preparation for the Final Mystery." Like Scriabin (in his conception of the "Mystery"); like Brian or Maw - Sorabji is a "maximalist" rather than a "minimalist." The aural impression is analogously of a primal nebula spinning off stellar and planetary systems, which evolve through the main sequence and burst into novae, only to die away as clouds of red glowing gas. These then provide the raw material for further grand spasms of cosmic creation and de-creation. My appetite is now whetted to hear "Opus Clavicembalosymphonicum," a similar four-hour contrapuntal exercise for piano and orchestra, or the "Jami" Symphony. for vocal soloists, choral forces, piano, and orchestra. It will probably never happen, but the keyboard works should garner a dedicated and persistent audience. Recommended to brave souls.

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Geoffrey Douglas Madge - Kaikhosru Sorabji Opus clavicembalisticum (2001).rar - 1.0 GB

Geoffrey Douglas Madge - Kaikhosru Sorabji Opus clavicembalisticum (2001).rar - 1.0 GB

![Iosu Izaguirre Sextet - Ilusio (2025) [Hi-Res] Iosu Izaguirre Sextet - Ilusio (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766936277_cover.jpg)

![Johnny Janis - Playboy Presents... Once In a Blue Moon (2015) [Hi-Res] Johnny Janis - Playboy Presents... Once In a Blue Moon (2015) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/29/hpechfkz7kpvyn01p0qdae2u4.jpg)

![Johannes Arzberger - Rebirth (2025) [Hi-Res] Johannes Arzberger - Rebirth (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/29/83zqlzou5l7cgdoiuiy231rth.jpg)