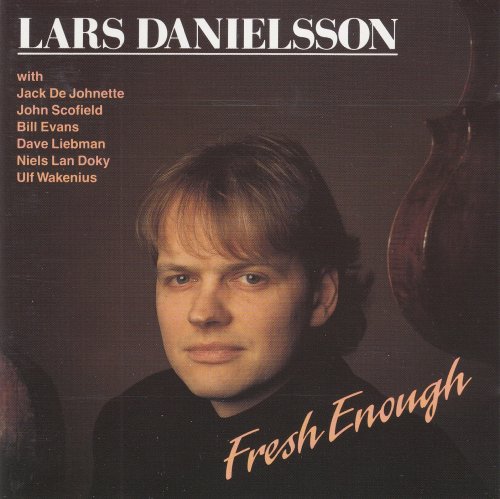

Bernardo Santos, Martim Almeida - A. Piazzolla, M. Ravel, M. Infante: Rhythmic Journeys, Dances for Two Pianos (2024)

Artist: Bernardo Santos, Martim Almeida

Title: A. Piazzolla, M. Ravel, M. Infante: Rhythmic Journeys, Dances for Two Pianos

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:02:40

Total Size: 168 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: A. Piazzolla, M. Ravel, M. Infante: Rhythmic Journeys, Dances for Two Pianos

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:02:40

Total Size: 168 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Le Grand Tango (Version for 2 Pianos)

02. Milonga de Angel (Version for 2 Pianos)

03. Soledad (Version for 2 Pianos)

04. La Valse, M.72 (Version for 2 Pianos)

05. Andalusian Dances: I. Ritmo

06. Andalusian Dances: II. Sentimento

07. Andalusian Dances: III. Gracia (El Vito)

08. Musiques d'Espagne: I. Farruca

09. Musiques d'Espagne: II. Montagnarde

10. Musiques d'Espagne: III. Tirana et Seguedille

Playing together and dancing together have much in common. In order to obtain synchronicity, harmony, and balance, both dancers and musicians must attune themselves to the music and to their partner(s), and this is a very delicate endeavour. It does not demand that artists renounce their personality – far from it!; indeed, a successful performance arises from the participation of all artists with their whole personality to the artistic task. However, it does require some degree of humility, of “obedience” (in the etymological meaning of the word, from the Latin ob-audire, which contains the verb for “listening”).

A beautiful choreography requires the careful planning of steps and movements in space, and the coordination of the dancing bodies. This implies that no dancer is entirely free to move as she or he pleases, but that they must respect the others’ space. The same applies to ensemble music-making, whereby the space of a musician’s freedom is somewhat limited by the freedom of others. Thus, playing together and dancing together are also beautiful examples of a creative, respectful, and balanced social interaction; they mirror what an ideal society should be.

Such a coordination may be easier or more difficult to achieve. In music, the ensemble made of two pianos is one of the most delicate and complex to manage. This is due to the physical size of the instruments, which prevents close proximity among the performing musicians (and being close to each other is what allows the artists to breathe together and to synchronize more easily their movements and gestures); and to the mechanical aspects of the instruments, since the slightest asynchronization is immediately evident in an instrument whose sound production is realized by hammers striking strings.

The “choreography” of the two-piano duet, therefore, is extremely difficult, but also, on the other hand, highly spectacular. With a daring image, it is as if each pianist had at his or her disposal a whole team of “dancers”: the polyphony which each piano can play turns each instrument into almost a whole orchestra, and two pianos playing together have a nearly limitless array of nuances, colours, and attacks at their disposal.

This Da Vinci Classics album explores the metaphor of the two pianos’ “dance” by presenting a series of pieces which are all related with dance, and in which the timbral palette of the two pianos is employed in full.

The soirée is opened by three pieces by Astor Piazzolla, a unique figure in the musical panorama of the recent past. Currently, both Piazzolla and his music have gained full membership in the “classical” repertoire; however, the merit for the inclusion of the tango within “classical” music is precisely Piazzolla’s. This Argentinian musician, of Italian descent, was in fact the first whose compositions and performances claimed the status of art music for the tango (even though highly artistic examples of tango music predated him). At the same time, and different from the great majority of today’s “classical” composers, Piazzolla’s music does not fear transcription, and, under this viewpoint, is strikingly similar to Bach (a composer Piazzolla admired deeply). It would be almost blasphemous to suggest that, for instance, a piece by Stockhausen be played indifferently on the accordion, guitar, or piano; whilst, by way of contrast, such transcriptions are commonly made and performed as concerns Piazzolla’s works. This happens also with the three pieces recorded here, which were originally conceived for other sound media, but which are beautifully rendered by the two-piano duet.

Grand Tango was originally written for cello and piano, in 1982, and dedicated to one of the greatest cellists of the twentieth century, Mstislav Rostropovič. However, the dedicatee did not play it until 1990, when he premiered it in New Orleans with pianist Igor Uriash, and only in 1996 did he record the piece. Within the piece, three main sections can be identified, although they are seamlessly connected to each other. The first, Tempo di tango, is a true presentation of the quintessence of this music, with its pronounced rhythms and clear patterns. The second part is freer and more cantabile, and the two instruments intertwine their respective melodic lines in a fascinating blend. The playful third section is full of irony and humour, and provides room for the display of the performers’ virtuosity.

Milonga del Ángel belongs in a cycle of four pieces which, just as Piazzolla’s Estaciones Porteñas, are ideally played together, but are also perfectly autonomous. They cycle is called Serie del Angel, and is composed of an opening Introduction, followed by the Milonga, by La Muerte del Angel (1962), and by a piece written almost as an afterthought, La Resurrección del Angel (1985). “Milonga” is a Spanish word meaning “tale”, but also “chitchat”; this musical genre was created in the 1870s between Argentina and Uruguay, and it is characterized by a syncopated binary time.

This piece was composed by Piazzolla for his own quintet, the Tango Nuevo, and its original instrumentation comprised accordion, violin, electric guitar, piano, and acoustic bass. Piazzolla recorded it in 1965, and, later, in his masterpiece album, Tango: Zero Hour (1986). The genesis of this work is due to a request by author Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz, who asked Piazzolla to compose the incidental music for his piece, Le Tango de l’Ange. It tells the story of an angel who appears in a Buenos Aires building with the purpose of purifying the soul of its dwellers. The pieces written by Piazzolla for this occasion were originally the Milonga and La Muerte, to which the other two were later added.

In spite of its connection with the world of dance, this Milonga is closer to the world of singing, and makes reference to the slow country milongas which used to be the object of contests of poetry and singing. The reference to angels is a rather common trait in Piazzolla’s stylistic and aesthetic world; his horizon is interspersed with supernatural presences, some of which are benevolent and luminous, whilst others are darker and ominous.

Soledad, translated as solitude or loneliness, is another of Piazzolla’s best known works, and is considered as a classic in the tango repertoire. The overall mood is that of nostalgia and melancholy, evoked through a poignant melody; originally, its accents were entrusted to the expressive voice of the bandoneon, but here again the piece has undergone a number of transcriptions, each of which brings to light new aspects of its structure and concept. Throughout the piece, Piazzolla’s use of dynamics, phrasing, and expression adds depth and emotion to the music, conveying the sense of solitude or introspection suggested by the title. Additionally, his incorporation of jazz and classical influences brings a unique flavor to the traditional tango form, making “Soledad” a distinctive and memorable composition within Piazzolla’s repertoire.

Maurice Ravel’s La Valse, like Piazzolla’s Milonga del Ángel, was also the result of an external prompting, which in turn responded to a deep artistic desire by the composer, but which, in the end, did not come out as initially imagined. Ravel was deeply fascinated by the world of Viennese waltzes, and had begun writing one in 1906, which should have been titled “Wien”, “Vienna”. However, the piece had been abandoned for years, also due to the political tensions which ultimately led to the fall of the very imperial world which the Viennese waltz used to symbolize. It was the Russian impresario and choreographer Diaghilev who asked Ravel to write something for him, and who therefore encouraged the composer to resume the composition of this evocation of a lost world. Notwithstanding this, when the piece was finished, after a time of compositional retreat in Lapras (Ardèche) Diaghilev objected that it was entirely unsuited to actual dancing; his opinion wounded Ravel deeply, and their relationship became very strained after this incident. The piece was eventually premiered in the two-piano version by the composer himself and Alfredo Casella, on October 23rd, 1923, in Vienna. In spite of the evidently tragical mood which pervades this depiction of the Viennese balls, Ravel claimed that he had not intended to portray the dissolution of the ancien régime, and that he had ideally set the piece in the midst of the Romantic era (1855). His own description of the piece runs as follows: “Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds gradually scatter: one sees at letter ‘A’ [a rehearsal marking in the score] an immense hall peopled with a whiling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth at the fortissimo at letter ‘B.’ An imperial court, about 1855”.

Ravel was therefore deeply intrigued by the “exotic” world of Imperial Vienna; however, his most constant fascination was that from Spain, and specifically from Andalusia. And it is by two works by Andalusian composer Manuel Infante that this album is completed. The Three Andalusian Dances brilliantly employ the traditional language of Spanish music in a fascinating blend with modern classical music. The first dance, Ritmo, is inspired by the sound of castanets and by the rasgueado, a typical technique of guitar playing, but also includes a moment of quieter contemplation. The second, Sentimiento, is dedicated to the composer’s wife and begins with an eloquent recitativo, which later gives way to a brilliant flamenco dance. The piece also includes the reproduction of hand-clapping and foot-stamping. Finally, Gracia (El Vito), which also exists in a solo piano version, is based on a famous folk melody, which is embellished with variations.

The Suite Musiques d’Espagne is likewise inspired by traditional Spanish music, featuring several dances typifying the various cultures coexisting in the Iberian Peninsula. The Farruca is a subgenre of Flamenco music, whose origins are probably to be found in the region of Galicia, to the Nort-West of Spain. Montagnarde evokes the atmosphere of folk music from the remote mountain regions, whilst Tirana et Seguedille are similar dances, whose origins and whose relation are still being studied by scholars of Iberian music.

Together, these pieces invite us to “dance” with the two pianos, and to enjoy the everlasting fascination of dance music and its connections with folk culture.

![Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765796826_cover.jpg)

![Stephen McCraven - Wooley the Newt (2025) [Hi-Res] Stephen McCraven - Wooley the Newt (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765906334_cover.jpg)