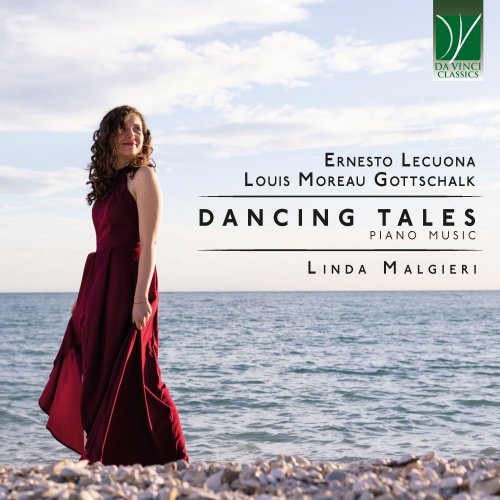

Linda Malgieri - Ernesto Lecuona, Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Dancing Tales, Piano Music (2024) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Linda Malgieri

Title: Ernesto Lecuona, Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Dancing Tales, Piano Music

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:00:51

Total Size: 217 / 942 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Ernesto Lecuona, Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Dancing Tales, Piano Music

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:00:51

Total Size: 217 / 942 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Piezas Características: Canto del guajiro

02. Piezas Características: La Habanera

03. Piezas Características: Mazurka glissando

04. Piezas Características: Preludio en la noche

05. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: La conga de media noche

06. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: Danza negra

07. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: ...Y la negra bailaba!

08. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: Danza de los Ñañigos

09. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: Danza Lucumi

10. Danzas Afro-Cubanas: La Comparsa

11. Bamboula, danse des nègres, Op. 2

12. La Savane, ballade créole, Op. 3

13. Le Bananier, chanson nègre, Op. 5

14. Le Mancenillier, sérénade, Op. 11

The dominance of rhythm in African and African-derived music is the pillar of this journey across piano pieces by Ernesto Lecuona and Louis Moreau Gottschalk, deriving from the combination of long melodic lines, often related to popular songs, with Caribbean and, in particular, Afro-Cuban rhythms. These are shown not only in the bass line, resembling drums and percussions, but in each rhythmic layer and in the melody itself. Each piece tells a story that evokes the spirit and energy of the composers’ native lands, Cuba and Louisiana, reflecting their historical and cultural landscape characterised by multifaceted influences. A vivid portrait of the Caribbean culture, in which dance has been used as form of expression since ancestral times, is rendered through this music, with those typical rhythmic patterns, such as tresillo, cinquillo and habanera, captivating and appealing to an European audience and loved by the American and Caribbean ones, unaccustomed to seeing their soul depicted in a music score.

Ernesto Lecuona’s pieces, with their evocative, at traits impressionism nature, often portray scenes of a normal daily life. Quatro Piezas Caracteristicas belong to what biographers consider being the third period of his compositional activity (1940-1963), mostly spent away from his beloved fatherland, as the freedom of expression and thought in Cuba was slowly suffocated by the rise of Communism. They showcase his ability to fuse traditional Cuban elements with a more classical form. The opening piece El canto del guajiro, apparently written after Lecuona heard a gardener singing outside of his home in Cuba, is a tribute to a Cuban farmer (guajiro) who portrays the different parts of his rural daily life through this “song”. He starts from the early morning with the theme that resembles birds singing, then he goes through the most energetic and busy part of the day, rendered doubling the theme with sixths and octaves and quickly passing from higher to lower registers, and finally arrives, after a sort of cadenza, to the final part of the day, when he nostalgically rethinks about his day, and, in a broader sense, about his life.

Habanera is the composer’s own piano arrangement from Act II of his opera El Sombrero de yarey, a piece with ABA’ structure permeated by the habanera rhythm that sways simple and graceful, but occasionally dark and melancholic, melodic lines, reflecting the spirit of Cuban music through the “dance from Havana”, as the name literally means, and demonstrating his understanding and feeling for the life of his native land.

Mazurka glissando is a clear example of the European influence over Cuban music, presenting the theme over the rhythm of an European, but still folk, dance, the mazurka. Lecuona enriches its brilliant melody with many glissandi, giving the piece an improvisational appearance.

Preludio en la noche (“Prelude in the night”), as the title suggests, captures a nocturnal atmosphere through expressive melodies, intricate harmonies and rhythmic nuances that convey a sense of mystery and emotion. After a quiet beginning, it rises to a soaring climax, proposing then the theme in a sort of orchestral-like notation that resembles films soundtracks, and it ends fading into quiet and peaceful “film credits”. Permeated by a “Hollywoodian” influence, the piece combines Lecuona’s souls as piano and soundtracks composer.

With the six Afro-Cuban Dances Lecuona develops and enriches the contradanza and danza genre, integral part of Cuban musical identity, using a ternary form, except for the first dance, which is in binary form, and incorporating African elements, such as syncopated, percussive and synchronized rhythms, into Cuban music. He thus creates a typical Afro-Cuban rhythmic and vibrant atmosphere and captures the animated and festive spirit of Cuban people during the great yearly carnival procession, the Comparsa, when the African heritage culture is celebrated by black and mix-raced musicians and dancers, regardless the provenance and the different traditions and beliefs.

The set opens with La conga de media noche (“The midnight conga”), a dance in two-four time with a march rhythm, whose name comes from the African conga drums, three percussions differentiated by register and function: the low pitch sustains the ostinato pattern with the middle conga that creates a similar but more melodic rhythmic pattern as fundament on which the high pitch conducts the leading melody with its improvisational style. In his dance, one of Lecuona’s most dissonant works that since the beginning shows unconventional harmonies, the Maestro masterly combines the different congas in both sections of the piece, juxtaposing the tribal and stressed character of the lower drums with a more elegant and refined jazz-like singing melody, conducted at the beginning by a single instrument, and in the final fff part by the whole big band.

The second and the third dance, Danza negra (“Black dance”) and …Y la negra bailaba! (“And the black women danced”), as their names imply, depict dance steps of an Afro-Cuban woman, gentle and charming in the former, through a dreamy melody over an ostinato that resembles African drums in the A section, fiery and full of energy in the latter, through a dance-like syncopated rhythm that accompanies the whole dance. The più mosso section represents the dancer solo, rendered by Lisztian-like octaves, in which her skills and talent are shown, this time more energetic and risoluto in Danza negra with stressed notes, sforzatos, ff sonority and wide left-hand leaps, and like on tiptoes, with piano and staccato octaves, in …Y la negra bailaba!

The following two pieces, Danza de los Ñañigos (“Ñañigos dance”) and Danza Lucumi (“Lucumi dance”), are permeated by a mystic and religious atmosphere, alluding to two different types of Afro-Cuban religious dances strictly connected to particular rituals and beliefs. In Danza de los Ñañigos, with a four bars introduction, the tribe appears in the comparsas and starts a pianissimo chant, then followed by a tribal dance with staccato passages and a syncopated ostinato rhythm, that, after a “Debussynian” partly impressionistic passage, explodes in an almost uncontrollable fff strepitoso projected towards the reprise of the chant, still in fff, representing a moment of exaltation when they can openly offer their music to their worshipped demons, and eventually ending in a ppp, when the Ñañigos return to their secret world.

Danza Lucumi presents a two bars ostinato with the bolero rhythm that accompanies an initial sorrowful chant that, after a poco più mosso middle section, bursts into a joyful music with accented ostinato octaves and triple forte sonority, as an offering to their deities “Orichas”.

The same rhythmic fervour can be seen in La comparsa, last dance of the set, in which all the Afro-Cuban tribes, accompanied by an initial ppp distant drum, approach the carnival procession and gather to dance, sing and worship their gods in the fff section, slowly disappearing after having told their stories as their music fades away in a melancholic diminuendo until a last drum beat can be heard.

From Cuban tales, the music narration proceeds with the later known as Louisiana Quartet by Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who captures the soul of the people from the 19th century Louisiana, melting pot of Creole, Afro-American and Caribbean cultures, in piano arrangements of Creole popular songs, reminiscences of his childhood in New Orleans. Written during his early period in Europe between 1844-1849, the four pieces show the composer’s exposure to Afro-Cuban influences prior to encountering African-derived music in the Caribbean and South America.

Bamboula, danse des nègres, op. 2, as the title and subtitle suggest, portrays an African dance permeated, from the beginning to the end, by the habanera rhythm. The four initial fff drum beats of the bamboula drum, made of bamboo, introduce the dance, playful and joyful in the first section, with a rhythmic first theme in D flat major and a more cantabile one in F sharp major in contrast with a staccato and energetic bass, melancholic and moving, instead, in the “Chopinian” B flat minor rubato theme of the development section, that becomes even heart-wrenching when cascades of fifths and sixths fall on the left hand chord theme variation and when a kind of polyphonic chant in the last variation, after a suspended dreamy and bucolic moment, mournfully re-evokes the beloved but distant homeland in Africa. At the end, a majestic and brilliant variation of the F sharp and D flat themes, using three repeating rhythmic layers, occurs con bravura.

La Savane, ballade créole, op. 3, is a theme and variation in E flat minor that, despite its lyrical melody, still contains complex rhythmic layers, at traits more important than the plaintive and melancholic melody itself, as in the variation with triplets or in the murmured music box-like movement of the last variation.

The rhythmical structure is still predominant in Le Bananier, chanson nègre, op. 5 and Le Mancenillier, sérénade, op. 11, where a drumming left hand accompanies the upbeat melody of the right hand, except in the last exposition of their themes, when the function of the two hands is reversed and sparkling semiquavers in the former piece, and percussive triplets in the latter, fall on the still rhythmic theme, passing through the highest and middle registers and giving back, again, a music box-like rendition.

And so the journey ends, with the essence and the eclecticism of the two composers and their cultural roots represented in this narration that creates a bridge between their different but complementary music heritage, emphasising how music transcends borders and unites different cultures, customs and traditions that blend into a harmonious interweaving of rhythms and melodies, providing an enchanting and educational listening experience.

![Falk Zenker - Innenwege (2026) [Hi-Res] Falk Zenker - Innenwege (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/08/fvzkzl9gzkslbf8lx8thi7kuq.jpg)

![Danny Scott Lane - House Of Alice (2026) [Hi-Res] Danny Scott Lane - House Of Alice (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/11/niuacokcorn3h1m7r4yhst5cn.jpg)

![Brian Lynch, Charles McPherson - Torch Bearers (2026) [Hi-Res] Brian Lynch, Charles McPherson - Torch Bearers (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/08/7w9gzslap9q13k2mlet4tfv7y.jpg)