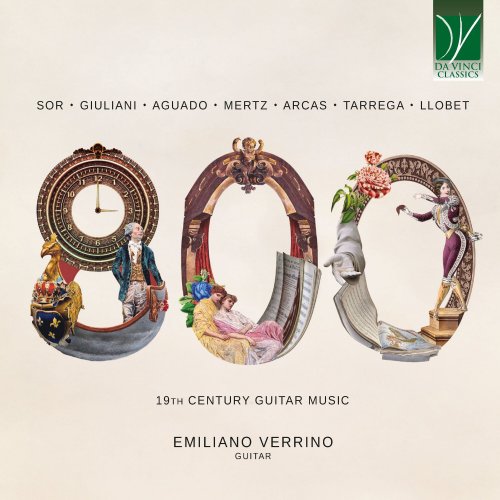

Emiliano Verrino - 800: 19th Century Guitar Music (2024)

Artist: Emiliano Verrino

Title: 800: 19th Century Guitar Music

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:12:40

Total Size: 303 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: 800: 19th Century Guitar Music

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:12:40

Total Size: 303 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Etude No. 22 in B Minor, Op. 35

02. Etude No. 11 in E Minor, Op. 6

03. Grande Ouverture, Op. 61

04. Gran Sonata Eroica, Op. 150

05. Rondo Brillante No. 2, Op. 2

06. Romanze

07. Elegie

08. Fantaisie Hongroise No. 1, Op. 65

09. Fantasía Sobre Motivos De La Traviata

10. Recuerdos De L'Alhambra

11. Capricho Árabe

12. Variaciones Sobre Un Tema De Fernando Sor, Op. 15

The nineteenth century can be seen as the period when the guitar finally acquired a standing of its own as one of the main instruments of the Classical tradition. It was a century of great technical discoveries, both as concerns instrument building and playing techniques. It was a century when great guitar virtuosi established international careers, touring Europewide – at times also to America – bringing new ideas, concepts, and fashions along. It was a century when the guitar claimed a status as a solo, unaccompanied instrument; when it was found that it was capable of singing as a human voice, of performing polyphony, of evoking the colours and sounds of other instruments, or of the whole orchestra; that it could both adopt and elude the idiosyncrasies of folk music. On the one hand, the near-identification of Spain with guitar and of guitar with Spain promoted an equation which fostered the employ of musical exoticism in a wide range of compositions. On the other hand, guitarists-composers coming from other countries, or Spaniards who did not passively accept the “folk” characterization, explored many other opportunities leading to a vast new repertoire.

This Da Vinci Classics CD offers the listener an intriguing itinerary through some iconic works of the Romantic and Late-Romantic repertoire for the guitar, displaying the full palette of its expressive resources, technical possibilities, and also of its sources of inspiration – from opera to Hungarian-style music, from Spanish echoes to Classical forms.

This recital opens with works by Fernando Sor, a musician from Catalunya whose life was deeply intertwined with the dramatic political events of his time, and who, as a result, travelled and lived abroad bringing with him his expertise, sensitivity, talent, and skill. In this recording, two of his works bear witness to the multifaceted inspiration of his genius. His Twelve Etudes op. 6, written during the time he spent in London, date from the early years of the nineteenth century; each is tailored upon a specific technical difficulty, but they also have a marked musical characterization. Technical difficulty does not perforce mean brilliancy: some of these Etudes are deep, reflective, enchanted. These are “concert Etudes”, meant for public performance, and they enjoyed continued success since the time of their premiere and of their publication. His op. 35, by way of contrast, is one further example of what a great composer can achieve with a seemingly, deceptively simple material. Like the “easy” piano pieces by Schumann, Debussy, or Bartók, these “Exercises” are no less beautiful to hear than useful for a pupil’s progress.

Contrasting with the miniature-size of these Exercises, Mauro Giuliani’s Grande Ouverture op. 61 is a masterpiece in terms of beauty, intensity, expressive power, and compositional skills. It is a milestone of the guitar repertoire, not only because it is played by most great performers of this instrument, but also for the historical significance it had. It was one of the pieces which contributed to establishing the guitar as a miniature orchestra, and to claim for it the status of a solo concert instrument. Giuliani was at the centre of his time’s cultural scene; he was appreciated, known, and fostered by some of the greatest musicians of the era (including Rossini and Beethoven), and he can be likened to Tárrega since both of them, in their respective times, were able to respond creatively to the challenges and opportunities offered by the technical advances in instrument building.

This Ouverture is akin to the great compositions in this style crafted by the Italian operatic composers of the era. It draws from the large repository of technical resources and of musical gestures of this genre, including the stately grandiosity of the French Overtures, some topoi of coeval music (such as the hunting style or the Sturm-und-Drang élans), and some idiomatic features of specific musical schools (such as the “Mannheim crescendo” or the Alberti bass).

By way of contrast, and rather ironically, doubts have been raised as to Giuliani’s authorship of his Gran Sonata Eroica precisely because it seems… too quintessentially Giuliani’s! In fact, there is plenty of Giuliani’s typical trademarks, to the point that some critics advanced the hypothesis that it is the work of an imitator rather than by the Italian master. These doubts are substantiated by the fact that very little is known about the origins of this work. In 1821, Giuliani wrote to publisher Ricordi claiming that he had written five pieces “in a style never before known”, and that one of them was a “Gran Sonata Eroica”, described by the composer as very lengthy and of a hitherto unknown style. Only in 1840, however, a work by this title was published as Giuliani’s op. 150; other dubious circumstances include its dedication and the absence of an autograph, to the point that Giuliani’s entry in The New Grove (2) omits this work from the list of Giuliani’s compositions. Still, today Giuliani’s authorship seems established, and the cases of self-plagiarism obviously detectable in the score seem to correspond to a practice which was not unusual, either for Giuliani himself or for his contemporaries. This is a composition with an ambitious breadth, a powerful architecture, a brilliant conception, and an intense expressive power – all weaved together in a combination of innovative melodies, harmonies, and technical solutions.

The Napoleonic era, with its political turmoil, international tensions, and philosophical challenges, impacted also the life of Dionisio Aguado, who sought refuge from the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in a small village where he lived a rather secluded life. This period of confinement prompted him to enter more deeply into the secrets of guitar playing, and to write numerous works which would impact the history of the modern guitar. His activity as a teacher encouraged him also to write guitar methods, and to create novel solutions for technical problems. Some of his intuitions would later become common knowledge among the wider community of the guitarists, whilst others (in spite of their brilliant conception) would soon be abandoned. For instance, Aguado had proposed the use of a device (a tripod) distancing the guitar’s body from the player’s, in order to favour the instrument’s resonance; this idea, however, did never gain universal acceptance.

Interestingly, one of Aguado’s main intuitions (i.e. that fingernails should be used for setting the string into vibration) was defended by him in polemics precisely with Fernando Sor (who, still, was a good friend and colleague of the Spaniard).

Aguado’s Introduction and Rondo op. 2 no. 2, recorded here, belongs in a series of three Rondo Brillants. It shows a patent kinship with Beethoven’s Grande Sonate Pathétique, op. 13, and this affinity is doubtlessly intentional. This piece, in fact, was published in 1827, the same year when Beethoven died. In spite of the seeming frivolity of a genre such as that of the “rondo brillant”, therefore, this piece demonstrates that virtuosity and depth can well go hand in hand.

Three works by Johann Kaspar Mertz follow suit. Mertz was probably the greatest Austrian guitarist-composer of his day; in turn, he was an acclaimed touring virtuoso. One event left an important mark in his life: an overdose of strychnine, which had been prescribed to him as a cure for neuralgia, nearly killed him. The process of recovery was long and painful, and some solace was provided to the convalescent musician by his wife’s performances at the piano. Through her, Mertz became familiar with the “salon repertoire” of his era, but also with the miniature works by Schubert and Schumann which seemingly belong in that same category, but in fact display a much greater profundity. Prompted by these models, Mertz sought to establish a similar repertoire for his instrument, and he certainly succeeded in this task. His Elegy, recorded here, is considered by most critics not only as one of his signature pieces, but also as one of the landmarks of the Romantic guitar. Here, the full pathos, expressiveness, intensity, and beauty which characterize the Romantic aesthetics appear clearly. Mertz’s career would have been crowned by the prize at the first Makaroff Competition in Brussels; however, alas, the composer died before the publication of the results, so that his victory was in fact a posthumous recognition of his career. His Romanze is excerpted from the Bardenklänge and is clearly reminiscent of the lyrical expansiveness of Franz Schubert’s works. Here, the guitar displays its potential as a melodic instrument, and seems to support and sustain itself, as if evoking a Lied.

Mertz also composed numerous Fantasias, where virtuosity, brilliancy, and technical prowess are fully displayed. They manage to combine the two poles of the Romantic aesthetics, i.e. the fiery and the emotional facets. Mertz was rather jealous of his Fantasies, and preferred not to have them published during his lifetime, for the reasons he explained as follows: “First, on seeing these, the publishers would say it was too difficult, that I would have to rearrange them. That would spoil the composition. Second, as long as these compositions remain in my briefcase, they remain new and are mine for my own concerts. Within six months after publication, they would become old. Further, they would become distorted and mutilated by those miserable guitarists who can only scratch the strings of the guitar”.

His Fantaisie Hongroise takes inspiration from the wave of “Hungarian” (or rather “gypsy”) music which was beloved by his contemporaries and the Romantics in general – starting with the pieces all’ingharese written by Haydn and Beethoven, up to Schubert, to Brahms, and especially to Liszt, whose Hungarian Rhapsodies clearly represent the model after which this piece is crafted.

Tárrega is represented here by pieces he wrote, arranged, or made known. Recuerdos de la Alhambra is one of his best-known works, and one of the most regarded in the entire guitar repertoire, thanks to its sheer technical complexity and to its exquisite melody, which emerges from the unceasing, and extremely difficult, tremolo. It was offered to a friend in 1899 as a birthday present. The Fantasia sobre motivos de La Traviata belongs in the host of operatic fantasies written for all kinds of instruments in the nineteenth century. It creatively weaves together many themes and motifs of Verdi’s beloved opera; it has also been the object of many musicological discussions, after which it was established that the true “authorship” should be ascribed to Arcas, Tárrega’s teacher, but that Tárrega’s version contains elements of originality.

If Recuerdos de la Alhambra brings the listener to Granada, the Capricho árabe suggests the atmospheres of Andalusia and Northern Africa; such is its importance, that it was played at Tárrega’s funeral. The “serenade”-like style of this piece suggests a romantic inspiration, but its structure does not correspond to that of the typical Spanish serenade – as a consequence, speculation is open as to its “real” inspiration.

Llobet, who was Tárrega’s pupil, is considered as the one ushering Impressionism into the world and repertoire of the guitar. With him, the circle of this album closes, since his Variaciones sobre un tema de Sor, op. 15, bring us back to the opening pieces; here, we find elaborations after Sor’s Folies d’Espagne, op. 15, and a new range of variations bearing witness to the passing of time and to the itinerary of guitar music throughout the nineteenth century.

![NYO Jazz - Live in Johannesburg (Live) (2025) [Hi-Res] NYO Jazz - Live in Johannesburg (Live) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765894703_zwp14vk90corb_600.jpg)