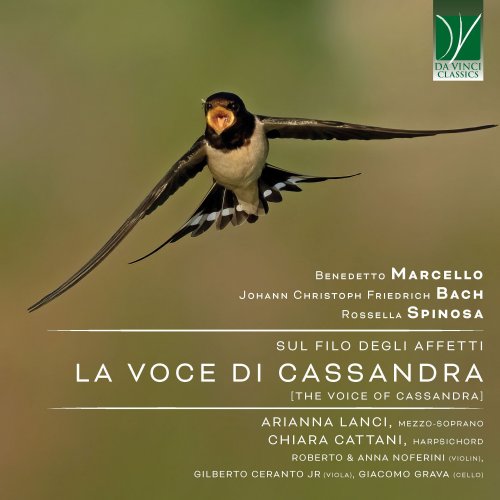

Giacomo Grava, Chiara Cattani, Roberto Noferini, Anna Noferini, Gilberto Ceranto Junior - B. Marcello, J. C. F. Bach, Spinosa: Sul filo degli affetti, La Voce di Cassandra (2024)

Artist: Giacomo Grava, Chiara Cattani, Roberto Noferini, Anna Noferini, Gilberto Ceranto Junior

Title: B. Marcello, J. C. F. Bach, Spinosa: Sul filo degli affetti, La Voce di Cassandra

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:52:06

Total Size: 561 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: B. Marcello, J. C. F. Bach, Spinosa: Sul filo degli affetti, La Voce di Cassandra

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:52:06

Total Size: 561 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD1

01. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: I. Odi, o Troja, Cassandra!

02. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: II. Sotto il piè de’ soldati, e de’ cavalli

03. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: III. Nell’aureo talamo

04. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: IV. Ma il furibondo Greco

05. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: V. Ahi spettacolo mesto

06. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: VI. E suonan le contrade ampie di Troja

07. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: VII. Altri pianti e lamenti

08. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: VIII. O come incalza colui che ferì Marte

09. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: IX. O misero, non sai

10. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: X. Oh discordie, oh perigli!

11. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: XI. Alla corrente del Xanto sbalza

12. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: XII. Vieni o sposa

13. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: XIII. Ei cade sulla polve

14. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata for Mezzo-Soprano and Harpsichord, S.240b: XIV. Chi nell’abisso mi sotterra

CD2

01. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: I. Odi, o Troja, Cassandra!

02. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: II. Sospirosetti va raddoppiando gli umidi baci

03. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: III. Non sempre riderai scherzosa Dea

04. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: IV. Nulla ottien dalla Diva il re dolente

05. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: V. Rimbombano dal lido i gridi di Minerva

06. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: VI. Dal fondo imo algoso il fiume sdegnoso

07. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: VII. Pur con l’aiuto di Vulcan

08. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: VIII. Vieni o sposa

09. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: IX. Ei cade sulla polve

10. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: X. Quanti danni! Quanti affanni

11. Cassandra, Dramatic Cantata, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord, Wf XVIII / 1, G. 46: XI. Chi nell’abisso mi sotterra

12. Cassandra, for Mezzo-Soprano, Strings and Harpsichord

The curse put on her by an unrequited god has condemned her to foretell the truth in the middle of the desert. Cassandra is alone because nobody listens to her monitions. Cassandra thus lives two lives: one in foresight, one in reality. Apollo has spitted in her mouth in revenge for having been rejected and after having promised her the gift of divination: a simple gesture that would deprive her, once and for all, of credibility.

A Trojan priestess, the daughter of Priam and Hecuba, Cassandra does not own the gift of persuasion, yet does not give up: she keeps speaking. This, to me, defines her strength and her potent modernity.

The priestess tries to warn her people about the tragic war after having intervened more than once on family matters, immediately recognising the threat posed by her brother Paris. Not only that: after ten years of attacks by the Greek army, Cassandra warns the Trojans about the wooden horse trick, and once again is not believed.

Ignored by all, at the apex of her disgrace – when all is lost and she is enslaved, humiliated and raped – she no longer speaks human words: to the Greeks, she seems to be completely delirious. In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, her appearance at the Mycenae stronghold is explosive by virtue of, indeed, her vocal onset: a long, inarticulate exclamation that I deemed perfect as the conclusion of the song by Rossella Spinosa, in the second chapter of an album series launched in the name of the myth of Ariadne. The state of abandonment of the Cretan princess on the island of Naxos is a cornerstone of the Melodrama, with a scene – Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna – accompanying us since 1608: a true manifesto of recitar cantando and the related Doctrine of the Affections. Within an aesthetics that makes the song a device to intensify the emotional result of words, the incipit represented by Arianna eventuates in Cassandra’s voice: one as mighty as it is ignored. A voice that becomes a swallow (the derogatory name given to the priestess) but that could also be a plant, a rock or another natural element unheard by humans.

Just like Arianna, Cassandra is alone. Just like Arianna, Cassandra chooses to not be quiet.

In Benedetto Marcello’s song, words are an unbridled force: music essentially plays a supporting role. The same text by renowned librettist Antonio Conti found a second musical life through Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, which pushed me to make an experiment to express the powerful modernity that the myth has always told us. The bond between the ancient and contemporary is the key to this second record: three Cassandras in a double album that represents a journey across the land of music, myth, poetry and femininity.

I thus asked Rossella Spinosa to give musical life to an extremely ancient script: Alessandra by the poet Lycophron (IV-III B.C.). And while Conti’s text – whose source is the Iliad as translated by Anton Maria Salvini – focuses, through Cassandra’s voice, on the events in the final years of the Trojan War, Lycophron’s text presents, in an epic poem written as a monologue, a kind of prophecy that is delivered orally by a servant to Priam. Segregated in a dark prison by her father, the protagonist spun a thread of enigmas, her words turning into poetry.

“Ma perché mai, infelice, abbaio alle sorde pietre, alle mute onde, alle selve cupe, emettendo dalla mia bocca un inutile canto? Ogni credibilità me l’ha tolta il dio di Lepsia, avvolgendo di menzogna le mie parole e la sapienza veridica dei vaticini, per essere stato respinto dal mio letto che desiderava. Pure, farà realizzare le profezie e qualcuno le apprenderà per suo danno, quando non ci sarà più nessun modo di aiutare la nostra patria, e allora loderanno la rondine posseduta.”

[Why, unhappy, do I call to the unheeding rocks, to the deaf wave, and to the awful glades, twanging the idle noise of my lips? For Lepsieus has taken credit from me, daubing with rumour of falsity my words and the true prophetic wisdom of my oracles, for that he was robbed of the bridal which he sought to win. Yet will he make my oracles true. And in sorrow shall many a one know it, when there is no means any more to help my fatherland and shall praise the frenzied swallow.]

![Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stanko - Unit (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 2/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765796826_cover.jpg)

![Tomasz Stańko, Tomasz Szukalski, Dave Holland & Edward Vesala - Balladyna (1976/2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stańko, Tomasz Szukalski, Dave Holland & Edward Vesala - Balladyna (1976/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765717548_cover.jpg)

![Tomasz Stańko - Zamek mgieł (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 3/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stańko - Zamek mgieł (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 3/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765795906_cover.jpg)