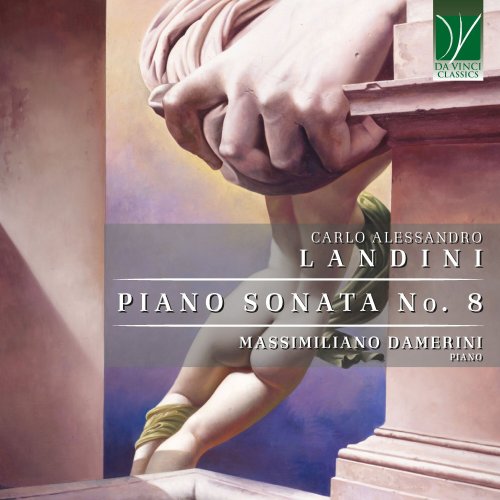

Massimiliano Damerini - Carlo Alessandro Landini: Piano Sonata No. 8 (2024)

Artist: Massimiliano Damerini

Title: Carlo Alessandro Landini: Piano Sonata No. 8

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:45:53

Total Size: 132 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Carlo Alessandro Landini: Piano Sonata No. 8

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:45:53

Total Size: 132 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Piano Sonata No. 8: I. Andante con moto

02. Piano Sonata No. 8: II. Calmo

03. Piano Sonata No. 8: III. Adagio

Writing music today is one of the most courageous, and even countercultural, activities one can undertake. The numbers of classical audiences are, sadly, constantly shrinking, in spite of significant increases in countries other than those of the Western tradition. The social dimension of music-making seems to disappear day after day; and the linguistic, communicative aspect of music faces unprecedented challenges. Whilst in the past there was (admittedly in the limited field of Western classical music) a largely shared musical language, of which the personal idioms of each composer of genius represented dialects, now the situation is exceedingly varied. At one extreme of the continuum, there are composers whose aesthetical stance might be summarized as “trying to please everybody”. As is well known, water is the only food which pleases everybody, and it does not stand out for its sapidity. In other words, “pleasant” music must perforce be entirely unoriginal, déjà vu, uncontroversial, and probably rather unartistic too.

At the other side of the spectrum, there are composers for whom originality is for originality’s sake. They craft a language of their own, which often purposefully assumes traits most people find incomprehensible, if not outright alien. Taking a stance and a standing near one or the other of these two poles is a matter of aesthetics, but also of ethics; something involving the entire poetic world of a musician.

But alongside language proper, there are also syntax, and, larger, than syntax, form. In music, syntax implies how to use the elements of language: for instance, the use of counterpoint, harmony, serialism and similar elements (or rhythm, or instrumentation…). And form: the formless does not exist, and some kind of form is absolutely needed in order to give a structure to musical events. Even aleatoric music, or improvisation, need a formal aspect (be it expressed in the simplest form, such as “play whatever note you like, for whatever length you wish”). However, how to relate oneself to the august forms of the classical tradition is a thorny aspect, which, in turn, presupposes and implies an aesthetic position.

The contemporary world, which normally tends to be wary of terms such as tradition, authority, and the likes, pursuing, instead, values such as freedom, autonomy, and creativity, is frequently against the adoption of musical forms and genres which have a longstanding and noble history. The very idea of writing a Sonata would seem absurd to many composers. The fact is, however, that forms and genres such as Sonatas or Ricercari (to name but two which will recur in the forthcoming lines) offer a solid basis on which a composer’s irreplaceable creativity can stand. By refusing the sanctioned forms of the Western tradition, just as by denying value to all established musical language, many composers put themselves at dead ends, or, at least, force themselves to find solutions for problems which have been already solved. This is a legitimate standing, of course, and it is not my goal here to deny validity to that artistic quest. However, I would also claim that it is at least as legitimate to devote one’s creativity to content, and to how that content relates with form, rather than creating new forms ex nihilo. In particular, if one refuses traditional forms, it is almost unavoidable that the resulting works will risk pulverization; in the best case, they will support themselves, and find a consistency, for a handful of minutes. No architect would build a bridge without taking into account what has been done with bridges in the past millennia; or, if he does so (as happens, for instance, with children playing with sticks), that bridge will be precarious and of a very limited size.

Carlo Alessandro Landini has clearly taken his own stance as concerns the problems outlined here. Against a dispersed, fragmented, splintered view of music, he supports and creates what he defines as “monumental music”: a music which is not ashamed of entering a fruitful dialogue with the music of the past; a music which “costs” the composer a lot, in terms of countless hours of gestation and of intellectual demand; a music which asks much also of the performer and of the listener, requiring careful preparation from the former and an equally careful listening of the latter; a music which claims for itself a place in the great museum of Western musical art, in the midst of the great works which have made history.

It should be clearly pointed out that this is not a manifestation of hybris on Landini’s part. Instead, and even though this might sound paradoxical, it is a demonstration of humility. It is precisely because he chooses to stand on the shoulders of the giants that he can afford such monumental works as his great, and famous, Piano Sonatas. It is precisely because he deliberately chooses to adopt the majestic tradition which is handed down to us, and to him, that he can emulate the artists of the past; precisely because he befriends them rather than closing his doors against them.

Landini has engaged a personal crusade of his own against the listening practices which are becoming increasingly common nowadays: casual listening, background music, what is called muzak and represents the degeneration of art into simple entertainment, and, at times, not even that. He writes demanding, but also very rewarding, music; music which cannot be listened half-heartedly or half-mindedly, but rather requires full concentration and attention. His first Sonata dates back to 1981, more than forty years ago. While to measure the worth of a musical work by its duration would be similar to an appreciation of visual art in terms of size and of a food in terms of weight, the striking, albeit superficial, element of time was already present. That Sonata lasted 73 minutes, which is more than twice as much as Beethoven’s Hammerklavier, one of the most gigantic and impressive Piano Sonatas of all times. Sonata no. 2, written thirty years ago (1994), outgrew her elder sister by one minute (74). It was with Sonata no. 5, however, that Landini created something truly unheard, truly unique, and something whose uniqueness was saluted as such by critics and scholars worldwide. It was a Sonata which could last between three and seven hours (!), and whose score filled more than 650 pages, written during five years of constant work.

Landini’s perspective has been masterfully summarized by the composer himself, both in a book-length monograph by the meaningful title of Misura e dismisura (which could be rendered as Proportion and disproportion, but the translation is not entirely faithful) and in an article-manifesto in twelve points demonstrating not only the justifiability, but also the need for “monumental music”. The first point of that manifesto is worth citing: “Looking around, we cannot find among the composers who […] live and work in today’s Europe anything like a ‘monumental’ will, a poetics of a resolute and at the same time extraordinary gesture. Something far from the obvious of the usual and ordinary language; something capable of bringing to light […] the spiritual and intellectual roots of such an ancient civilization as is our own”. It is against what he perceives as a malady of the Western soul that Landini fights his personal struggle: “We miss what could embody and translate into the language of music, today, the summa of the spirit and of the monumental contemporary art, in an era in which it seems impossible to conceive anything spiritual or monumental”. The spiritual and the monumental, for him, are the epos “of true life”, seen against a “romantic ideology of the livable” or as a “listening adventure which faces the listener when it becomes, or remains, merely listenable”.

His Sonata no. 8 continues on the path traced by her elder siblings. The recording issued in this Da Vinci Classics album is in turn a “monument”, not only for the work it presents, but also for what it represents from the viewpoint of the performer. Massimiliano Damerini, who premiered the work and who was one of the finest Italian pianists, and one of Landini’s longtime collaborators, would unexpectedly die soon after that performance; and the recital recorded here would become the very last of that genius pianist.

The Sonata bespeaks a particular moment in the composer’s life, bound to some particularly sorrowful experiences, and it also represents, in this view, a cathartic experience. The seemingly polished architectures of the first movement seem to allude to our common tendency to embrace order and clarity when life appears to crumble around us. If it might suggest the impression of an “empty fortress” (to cite Bruno Bettelheim’s memorable expression) it is only because it needs to be put in dialogue with the other movements. The first movement seems to proceed in waves, built on recurring intervallic patterns; with long stretches where the dynamic nuances are narrow (between p and mf), and with rich counterpoint creating multiple layers of sound. Thus, even though there is a certain deliberate static element in this piece, it never remains static, but rather seems to generate progressive climaxes. The rhythm of siciliana, which recurs occasionally, and the broader waves of semiquavers, impress a dynamism within a structure whose algid beauty stands as a memento of the transient quality of time.

The second movement, Calmo, continually plays with changing metres and intervallic combination which confer great coherence to the whole. It also transmits a feeling of uncertainty due to the frequent alternations of ritenuto and in tempo. It is as if the choice of leaving the relatively safe harbour of structure, represented by the first movement, had left the musical protagonist in search of a way out, in an itinerary punctuated by doubts and afterthoughts.

The third movement, Quasi una fantasia (with more than an echo of Beethoven) seems to accept the “ground zero” established by the former movements, and to timidly build in on it. There are prevailingly ascending movements, as if in the effort to find a constructive voice in the midst of suffering. Its contemplative Adagio is followed by a brisk Gaillarde, which does not follow the ancient model too strictly, but rather evokes a moment of reawakening. A very improvisational style characterizes the two Ricercari: all three sections, in their names and in their approach, recall Renaissance music. The Morendo, doloroso, brings the work to a sad, but poignant, closing, crowning this contemplation of death, of sorrow, of grief, but also of hope, of life, of the sacred, with a music fading into silence.