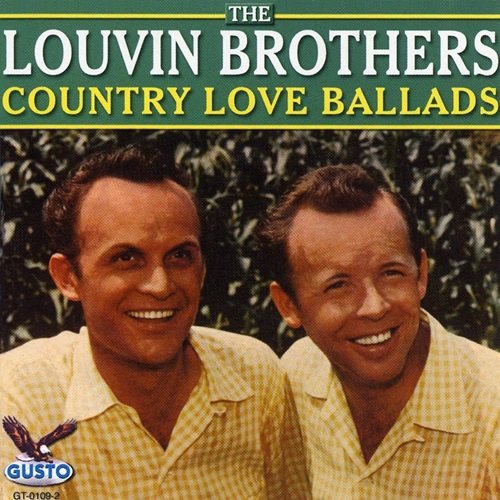

The Louvin Brothers - Country Love Ballads (2024)

- 07 Oct, 17:19

- change text size:

Facebook

Twitter

Artist: The Louvin Brothers

Title: Country Love Ballads

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Capitol Nashville

Genre: Country

Quality: Flac (tracks)

Total Time: 28:59

Total Size: 186 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Country Love Ballads

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Capitol Nashville

Genre: Country

Quality: Flac (tracks)

Total Time: 28:59

Total Size: 186 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Are You Wasting My Time 2:04

02. If I Could Only Win Your Love 2:21

03. Today 2:24

04. Read What's In My Heart 2:12

05. I Wonder If You Know 3:16

06. Memories And Tears 2:23

07. On My Way To The Show 2:07

08. My Heart Was Trampled On The Street 2:31

09. She Will Get Lonesome 2:22

10. Red Hen Hop 2:40

11. Blue 2:19

12. Send Me The Pillow You Dream On 2:20

Arguably the finest close-harmony duo in the history of country music, the Louvin Brothers were standard bearers of the traditions of Appalachian music at a time when Nashville was moving country music into a more modern direction. Raised on the sounds of the Delmore Brothers, the Monroe Brothers, the Carter Family, and the Blue Sky Boys, Ira and Charlie Louvin blended their tenor voices with a remarkable skill, creating a powerfully emotional sound reinforced by Ira's expert mandolin work. The siblings were steeped in gospel music, and while they enjoyed their greatest success with secular material, their love songs were always chaste, and their spiritual numbers often dealt with the severe consequences of sin. The Louvin Brothers began performing together in 1940, and struggled through years of career disappointments, unsuccessful record deals, and hiatuses brought on by military service before they scored their first hit in 1955 with "When I Stop Dreaming." The rise of rock & roll and countrypolitan had little impact on the Louvin Brothers' style, as they remained stubbornly traditionalist in classics like "Cash on the Barrelhead" and "My Baby's Gone," though they did record ambitious concept albums like 1956's Tragic Songs of Life and 1960's Satan Is Real that married their classic sound to dark and unforgiving themes. Ira Louvin's struggles with alcohol and anger led to the duo's breakup in 1963, but they would go on to influence country traditionalists like Marty Stuart and Gillian Welch as well as country-rock pioneers the Byrds, Gram Parsons, and Emmylou Harris and alt-country artists Will Oldham and Freakwater.

Born and raised in the Appalachian mountains in Alabama, both Charlie (born Charlie Elzer Loudermilk, July 7, 1927; died January 26, 2011) and Ira (born Lonnie Ira Loudermilk, April 21, 1924; died June 20, 1965) were attracted to the close-harmony country brother duets of the Blue Sky Boys, the Delmore Brothers, the Callahan Brothers, and the Monroe Brothers when they reached their adolescence. Previously, they had sung gospel songs in church, and their parents encouraged them to play music, despite the family's poverty. Ira began playing mandolin while Charlie picked up the guitar, and the two began harmonizing. After a while, they began performing at a small, local radio station in Chattanooga, where they frequently played on an early-morning show.

The Brothers' career was interrupted in the early '40s when Charlie joined the Army for a short while. While his brother was in the service, Ira played with Charlie Monroe. Once Charlie returned from the Army, the duo moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where they received a regular spot on a WROL radio show; they later moved to WNOX. Around this time, they decided to abandon their given name for Louvin, which appeared to be a better stage name. (Their cousin John D. Loudermilk retained the family name.) Following their stint in Knoxville, they moved to Memphis, where they broadcast on WMPS and cut one single for Apollo Records. After their brief stay in Memphis, they returned to Knoxville.

In 1949, the Louvin Brothers recorded a single for Decca Records which failed to make much of an impact. Two years later, they signed with MGM Records and over the next year recorded 12 songs. Shortly after their MGM sessions were finished, Charlie and Ira moved back to Memphis, where they worked as postal clerks while playing concerts and radio shows at night. Eventually, they earned the attention of Acuff-Rose, who signed the duo to a publishing contract. (A collection of the publishing demos they cut for Acuff-Rose, Love and Wealth: The Lost Recordings, would be released in 2018.) Fred Rose, the owner of the publishing house, helped the duo sign a contract with Capitol Records. The Louvins' debut single for the label, "The Family Who Prays," was a moderate success (it would later become a gospel standard), yet they were unable to capitalize on its success because Charlie was recalled by the Army to serve in the Korean War.

Upon Charlie's discharge from the Army, the Louvins relocated to Birmingham, where they planned to restart their career through appearances on the radio station WOVK. However, a duo called Rebe & Rabe had already carved out a close-harmony niche in the area, using several of the Louvins' own songs. When Charlie and Ira were reaching a point of desperation, Capitol's Ken Nelson was able to convince the Grand Ole Opry to hire the duo. Prior to joining the Opry, the duo had been marketed as gospel artists, but they began singing secular material as soon as they landed a slot on the show, primarily because a tobacco company sponsoring its broadcast told the Opry and the Louvins "you can't sell tobacco with gospel music." While they didn't abandon gospel, the Brothers began writing and performing secular material again, starting with "When I Stop Dreaming." The single became a Top Ten hit upon its release in the fall of 1955 and would eventually become a country standard. It was followed shortly afterward by "I Don't Believe You've Met My Baby," which spent two weeks at number one early in 1956. No less than three of the duo's other singles -- "Hoping That You're Hoping," "You're Running Wild," "Cash on the Barrel Head" -- reached the Top Ten that year, and they also released the albums Tragic Songs of Life and Nearer My God to Thee. The Louvins' success in 1956 was particularly impressive when considering that rock & roll was breaking big that year, sapping the sales of many established country artists.

However, the Louvins weren't able to escape being hurt by rock & roll. They had two relatively big hits in 1957 ("Don't Laugh" and "Plenty of Everything but You"), "My Baby's Gone" reached the Top Ten in late 1958, and their classic version of the traditional ballad "Knoxville Girl" was a moderate hit in early 1959, but those four hit singles arrived in the space of three years; they charted four songs in 1956 alone. Soon, the Louvins were receiving pressure from Capitol to update their sound. They tried to cut a couple of rockabilly numbers, but they were quite unsuccessful. Eventually, Ken Nelson suggested that the duo abandon the mandolin in order to appeal to the same audience as the Everly Brothers. The Louvins didn't accept his advice, but the remark did considerable damage to Ira's ego and he began to sink into alcoholism.

The Louvin Brothers continued to record during the early '60s, turning out a number of theme albums -- including tributes to the Delmore Brothers and Roy Acuff, as well as gospel records like Satan Is Real -- as well as singles. "I Love You Best of All" and "How's the World Treating You" reached numbers 12 and 26, respectively, in 1961, the first year they had two hit singles since 1957. However, the duo began fighting frequently, and Ira's alcoholism worsened. Following one last hit single, "Must You Throw Dirt in My Face," in the fall of 1962, the duo decided to disband in the summer of 1963.

Charlie and Ira both launched solo careers on Capitol Records shortly after the breakup. Charlie was the more successful of the two, with his debut single, "I Don't Love You Anymore," reaching number four upon its summer release in 1964. For the next decade, he racked up a total of 30 hit singles, though most of the records didn't make the Top 40. Ira's luck wasn't as good as his brother's. Shortly after the Louvins disbanded, he had a raging, alcohol-fueled argument with his third wife, Faye, that resulted in a shooting that nearly killed him. He continued to perform afterward, singing with his fourth wife, Anne Young. The duo were performing a week of concerts in Kansas City in June of 1965 when they were both killed in a car crash in Williamsburg, Missouri. After his death, his single "Yodel, Sweet Molly" became a moderate hit.

The Louvin Brothers' reputation continued to grow in the decades following their breakup, as their harmonies and hard-driving take on traditional country provided the blueprint for many generations of country and rock musicians. The Everly Brothers were clearly influenced by the duo, while country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons drew heavily from the Louvins' deep catalog of classic songs, recording "The Christian Life" with the Byrds and "Cash on the Barrelhead" as a solo artist. The Louvin Brothers and their music are truly legendary.

Born and raised in the Appalachian mountains in Alabama, both Charlie (born Charlie Elzer Loudermilk, July 7, 1927; died January 26, 2011) and Ira (born Lonnie Ira Loudermilk, April 21, 1924; died June 20, 1965) were attracted to the close-harmony country brother duets of the Blue Sky Boys, the Delmore Brothers, the Callahan Brothers, and the Monroe Brothers when they reached their adolescence. Previously, they had sung gospel songs in church, and their parents encouraged them to play music, despite the family's poverty. Ira began playing mandolin while Charlie picked up the guitar, and the two began harmonizing. After a while, they began performing at a small, local radio station in Chattanooga, where they frequently played on an early-morning show.

The Brothers' career was interrupted in the early '40s when Charlie joined the Army for a short while. While his brother was in the service, Ira played with Charlie Monroe. Once Charlie returned from the Army, the duo moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where they received a regular spot on a WROL radio show; they later moved to WNOX. Around this time, they decided to abandon their given name for Louvin, which appeared to be a better stage name. (Their cousin John D. Loudermilk retained the family name.) Following their stint in Knoxville, they moved to Memphis, where they broadcast on WMPS and cut one single for Apollo Records. After their brief stay in Memphis, they returned to Knoxville.

In 1949, the Louvin Brothers recorded a single for Decca Records which failed to make much of an impact. Two years later, they signed with MGM Records and over the next year recorded 12 songs. Shortly after their MGM sessions were finished, Charlie and Ira moved back to Memphis, where they worked as postal clerks while playing concerts and radio shows at night. Eventually, they earned the attention of Acuff-Rose, who signed the duo to a publishing contract. (A collection of the publishing demos they cut for Acuff-Rose, Love and Wealth: The Lost Recordings, would be released in 2018.) Fred Rose, the owner of the publishing house, helped the duo sign a contract with Capitol Records. The Louvins' debut single for the label, "The Family Who Prays," was a moderate success (it would later become a gospel standard), yet they were unable to capitalize on its success because Charlie was recalled by the Army to serve in the Korean War.

Upon Charlie's discharge from the Army, the Louvins relocated to Birmingham, where they planned to restart their career through appearances on the radio station WOVK. However, a duo called Rebe & Rabe had already carved out a close-harmony niche in the area, using several of the Louvins' own songs. When Charlie and Ira were reaching a point of desperation, Capitol's Ken Nelson was able to convince the Grand Ole Opry to hire the duo. Prior to joining the Opry, the duo had been marketed as gospel artists, but they began singing secular material as soon as they landed a slot on the show, primarily because a tobacco company sponsoring its broadcast told the Opry and the Louvins "you can't sell tobacco with gospel music." While they didn't abandon gospel, the Brothers began writing and performing secular material again, starting with "When I Stop Dreaming." The single became a Top Ten hit upon its release in the fall of 1955 and would eventually become a country standard. It was followed shortly afterward by "I Don't Believe You've Met My Baby," which spent two weeks at number one early in 1956. No less than three of the duo's other singles -- "Hoping That You're Hoping," "You're Running Wild," "Cash on the Barrel Head" -- reached the Top Ten that year, and they also released the albums Tragic Songs of Life and Nearer My God to Thee. The Louvins' success in 1956 was particularly impressive when considering that rock & roll was breaking big that year, sapping the sales of many established country artists.

However, the Louvins weren't able to escape being hurt by rock & roll. They had two relatively big hits in 1957 ("Don't Laugh" and "Plenty of Everything but You"), "My Baby's Gone" reached the Top Ten in late 1958, and their classic version of the traditional ballad "Knoxville Girl" was a moderate hit in early 1959, but those four hit singles arrived in the space of three years; they charted four songs in 1956 alone. Soon, the Louvins were receiving pressure from Capitol to update their sound. They tried to cut a couple of rockabilly numbers, but they were quite unsuccessful. Eventually, Ken Nelson suggested that the duo abandon the mandolin in order to appeal to the same audience as the Everly Brothers. The Louvins didn't accept his advice, but the remark did considerable damage to Ira's ego and he began to sink into alcoholism.

The Louvin Brothers continued to record during the early '60s, turning out a number of theme albums -- including tributes to the Delmore Brothers and Roy Acuff, as well as gospel records like Satan Is Real -- as well as singles. "I Love You Best of All" and "How's the World Treating You" reached numbers 12 and 26, respectively, in 1961, the first year they had two hit singles since 1957. However, the duo began fighting frequently, and Ira's alcoholism worsened. Following one last hit single, "Must You Throw Dirt in My Face," in the fall of 1962, the duo decided to disband in the summer of 1963.

Charlie and Ira both launched solo careers on Capitol Records shortly after the breakup. Charlie was the more successful of the two, with his debut single, "I Don't Love You Anymore," reaching number four upon its summer release in 1964. For the next decade, he racked up a total of 30 hit singles, though most of the records didn't make the Top 40. Ira's luck wasn't as good as his brother's. Shortly after the Louvins disbanded, he had a raging, alcohol-fueled argument with his third wife, Faye, that resulted in a shooting that nearly killed him. He continued to perform afterward, singing with his fourth wife, Anne Young. The duo were performing a week of concerts in Kansas City in June of 1965 when they were both killed in a car crash in Williamsburg, Missouri. After his death, his single "Yodel, Sweet Molly" became a moderate hit.

The Louvin Brothers' reputation continued to grow in the decades following their breakup, as their harmonies and hard-driving take on traditional country provided the blueprint for many generations of country and rock musicians. The Everly Brothers were clearly influenced by the duo, while country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons drew heavily from the Louvins' deep catalog of classic songs, recording "The Christian Life" with the Byrds and "Cash on the Barrelhead" as a solo artist. The Louvin Brothers and their music are truly legendary.

![Marvin Birungi - Soul Vaxnation (2026) [Hi-Res] Marvin Birungi - Soul Vaxnation (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771660075_500x500.jpg)

![Joe Pass - Virtuoso (1974) [2025 DSD256] Joe Pass - Virtuoso (1974) [2025 DSD256]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771609997_ff.jpg)