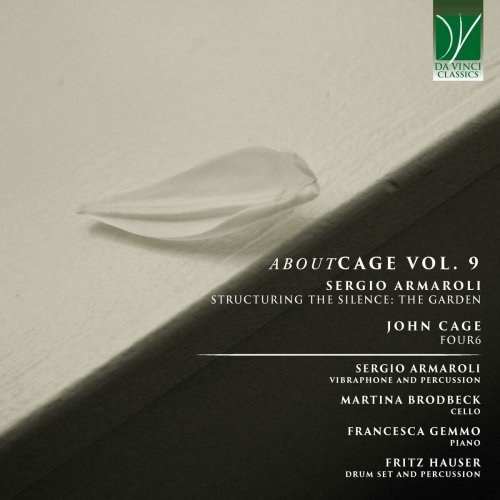

Sergio Armaroli - AboutCage 9: Structuring the Silence: The Garden | Four6 (2024) Hi-Res

Artist: Sergio Armaroli, Martina Brodbeck, Francesca Gemmo, Fritz Hauser

Title: AboutCage 9: Structuring the Silence: The Garden | Four6

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) / FLAC 24 Bit (44,1 KHz / tracks)

Total Time: 61:42 min

Total Size: 179 / 478 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: AboutCage 9: Structuring the Silence: The Garden | Four6

Year Of Release: 2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) / FLAC 24 Bit (44,1 KHz / tracks)

Total Time: 61:42 min

Total Size: 179 / 478 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Structuring The Silence: the Garden (2023)

02. Four6 (1992)

John Cage not only challenged deeply the concept of what counts as music, but also of what counts as musical score. He is the quintessential, archetypal figure of musical avantgarde; similar to his counterparts in the visual arts, he delighted in exposing what he felt as the stereotypical acquisitions and expectations of the art-loving bourgeoisie.

Jackson Pollock created works of art by exploding paint-filled balloons: both the act itself and its visual result were miles aways from the practice, study, and final appearance of works coming from visual art academia.

Critics contended that anyone could do that, including a toddler or a chimpanzee, and that “art” was something rather different – take Monna Lisa, or Giotto, for instance. Indeed, the contention was right, but it hit the wrong target. Pollock was obviously aware that anybody could explode a paint-filled balloon, and that the final result was the product of chance, an unpredictable coloured shape determined only by physical phenomena uncontrolled by the artist. The point was that the “artistic” component of Pollock’s work consisted in his idea. The idea of creating artworks by hitting paint-filled balloons could not come to anybody. The utter originality of Pollock’s artistry was found precisely there, in imagining new ways of making art, and even in considering art what nobody before him could think of as art.

Something similar happened with Cage. The highest expressions of his talent and genius are found in his ideas about what counts as music and what counts as a musical score. The principle behind his notorious 4’33’’ is so well known that it is almost a commonplace to discuss it. For Cage, the random sounds happening within the space of four minutes and thirty-three seconds (in which the deliberate intention was to keep silence) are “music”. And, for him, the verbal description generating it (basically instructing the player – or players! – to stay silent for four minutes and thirty-tree seconds) is a musical score.

After Cage, these ideas were – slowly but steadily – subsumed and assumed by the musical world, so that today graphical scores, verbal scores and the likes are commonly accepted as “other” forms of writing and composing music.

This may help us to make a further point, concerning how philosophical and aesthetical thought relates with music. We have just seen that Pollock had no control whatsoever (and did not want to have any control) on the final appearance of his works of visual art. If two adjacent balloons were filled, respectively, with green and red paint, the artist did not decide which of them should explode, and even less which shape would the spilled paint determine on the canvas. It was a matter of chance, depending on which balloon was hit. As said already, art was in the idea; the final visual appearance was almost an accessory.

This implies a disjunction between “body” and “mind” (or “soul”) which is rather typical for the modern era and determines a fracture, a hiatus, between this modern and postmodern concept and the one preceding it. Within a Christian concept of art, “body” and “mind/soul” are integrated, not in opposition; the “concept” behind Leonardo’s Monna Lisa and the visual appearance of the painting are not separable. Had Leonardo had the “concept” of the Monna Lisa painting but not the ability to paint it, that would not have counted as art. Had (per absurdum) a Pollock-style random pouring of paint on a canvas produced the Monna Lisa, that would also not have counted as art.

With Cage, the aesthetic perspective is similar, in the aural field. When the child Mozart was brought in the European Courts by his father, and asked to improvise on a given theme or freely, the idea was that the child Mozart was the genius, the artist, not those asking him to improvise. And, again, should a cat walking on a keyboard have produced the Jupiter Symphony, that cat would not have been considered as an artist of Mozart’s standing.

Cage, instead, contended – with his works of art – that the concept is what counts. And, furthermore, this has an even more dramatic impact on music than Pollock’s on visual art. In the end, in fact, a particular Pollock canvas does have a definite visual appearance. Although two “paintings” by Pollock may have been produced with the same technique, in the end their look is precisely defined, and an expert in Pollock’s works will be able to recognize, at sight, which painting is the one shown to him or her.

By way of contrast, not even the greatest expert of Cage’s music could recognize, upon hearing, a performance of some of his works as such. Two different renditions of Four6, for instance, will sound completely different, and it is practically impossible to identify them as performances of Four6, unless the listener has the score and a chronometer.

This is because the “score” of Four6 does not determine in the least the pitches, rhythms, sounds, durations, and not even the instrument or instruments that have to play.

Four6 belongs in a “numerous” series of pieces by Cage – “numerous” is in inverted commas because the series under discussion is made of many pieces, but also because those works are known as “number pieces”. Each of them has a title composed of two numbers, the first of which is written as a word, and the second as a digit. The first number indicates the number of players which ought to perform in the piece. Through the second number, Cage identifies how many pieces he had written, until a certain moment, for that number of players, in the series of “number pieces”.

Practically speaking, therefore, Four6 is a piece for four players, and it is the sixth Cage wrote for a “quartet” in the series of “number pieces”.

The work was first conceived in 1990, but Cage restructured it in 1992; it received its world premiere in the same year, on July 23rd, in New York, at Central Park Summerstage. It was the last public appearance of Cage, a mere fortnight before his death. The piece’s duration is 30 minutes: this is one of the very few detailed and prescribed elements of Cage’s “score”, as we will shortly see.

The volume containing the instructions for a rendition of Four6 contains in fact a verbal introduction, and some pages of “score” (whose visual appearance, however, would suggest to very few people the idea of a musical score).

Indeed, even the claim that Four6 is a piece for four players, as stated before, is misleading. Cage’s instruction, on the book’s first page, reads literally: “for any way of producing sounds (vocalization, singing, playing of an instrument or instruments, electronics, etc.)”. This implies that there should be four “layers”, each made of a different kind of sound production, but these need not necessarily be realized by four different players. For instance, a single performer could sing, produce other sounds with his or her voice, clap his or her hands, and rub a piano’s strings. This would actually count as a performance of Four6, but – at the same time – being a performance realized by a single musician, it would also count as a performance of One7, another “number piece” by Cage. Also the piece’s dedication mirrors this double titling and double destination: One7 is dedicated to Pauline Oliveros on her sixtieth birthday, while Four6 bears the same dedication but also adds Joan La Barbara, William Winant, and Leonard Stein (the performers of the world premiere).

The following instructions represent the remainder of the verbal component of Cage’s “score”: “Choose twelve different sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude, overtone structure, etc.). Play within the flexible time brackets given. When the time brackets are connected by a diagonal line, they are relatively close together. When performed as a solo, the first player’s part is used and the piece is called One7”.

In other words, the performers should elect and number twelve sounds. Then they can begin producing that sound at any moment within a “flexible time bracket” (i.e. a temporal indication with a chronometrical beginning and end), and finish that sound production similarly.

Thus, sounds superimpose, and can create something akin to “harmony” – the nemesis of avantgarde composers. Cage himself seemed to be surprised by this, as he stated in 1990 (i.e. in the year when Four6 was first imagined): “I’m surprised at almost all the ideas that come to my head, because they have to do with harmony”, he said.

Cage’s concept is echoed, and creatively answered, by Sergio Armaroli, who is featured in this CD not only as a performer, but also as a composer (given, and not granted, that these two categories can be applied to the repertoire under discussion). Structuring the Silence. Eight Part(s) has had an even longer gestation than Cage’s Four6, extending, as it did, over a period of seven years. It is scored “for solo, two, four, and more performers”, thus mirroring the utter freedom of Cage’s concept.

The first verbal instructions given by Armaroli are purposefully and remarkable similar to Cage’s, but also subtly different, as will be clear by reading them side by side: “Choose all different sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude, tempo, overtone structure, duration, etc.) and nine elements: gestures, intention, words and other suggestion(s) etc. Durations and dynamics are free. The sounds to be made are long and short or very short. When performed as a Solo, for One Player, choose cymbals and/or drums”. The “score’s” following pages are made of time brackets (like Cage’s), but are divided by number of players – so there are instructions for one player, for two, etc.

Other instructions are given later, in Structuring the Silence. Erratum Version. Inside Outside (2018); here, the indications are tangibly different from Cage’s, even though the connection between the two composers remains clear and takes the form of a posthumous and explicit homage by the younger to the older musician. Other variants of Structuring the Silence take the name of “Habitat”; “for Angelica”; “Erbario sonoro”; “Extended (per Quattro | inResonance”; and “In the Garden (…nel Giardino)”, recorded here. Here the sounds to choose are nine or groups of nine. The allusion to the “garden” is explained later: “the tape “is the Garden”: any tape (of natural sounds or other: birds etc…) it must not be intended as a background but must have the same level of amplification (stereo or quadriphonic) of the instruments, mixing with the sounds of the environment in a single sound landscape: in resonance, in the quartet”. Further, resonance has a fundamental role, and basically structures the piece.

Thus, the crossing paths of Cage and Armaroli become the source of renewed, fresh creativity, in a productive interaction which involves virtually all kinds of sounds found in nature or artificially produced.

Chiara Bertoglio

Jackson Pollock created works of art by exploding paint-filled balloons: both the act itself and its visual result were miles aways from the practice, study, and final appearance of works coming from visual art academia.

Critics contended that anyone could do that, including a toddler or a chimpanzee, and that “art” was something rather different – take Monna Lisa, or Giotto, for instance. Indeed, the contention was right, but it hit the wrong target. Pollock was obviously aware that anybody could explode a paint-filled balloon, and that the final result was the product of chance, an unpredictable coloured shape determined only by physical phenomena uncontrolled by the artist. The point was that the “artistic” component of Pollock’s work consisted in his idea. The idea of creating artworks by hitting paint-filled balloons could not come to anybody. The utter originality of Pollock’s artistry was found precisely there, in imagining new ways of making art, and even in considering art what nobody before him could think of as art.

Something similar happened with Cage. The highest expressions of his talent and genius are found in his ideas about what counts as music and what counts as a musical score. The principle behind his notorious 4’33’’ is so well known that it is almost a commonplace to discuss it. For Cage, the random sounds happening within the space of four minutes and thirty-three seconds (in which the deliberate intention was to keep silence) are “music”. And, for him, the verbal description generating it (basically instructing the player – or players! – to stay silent for four minutes and thirty-tree seconds) is a musical score.

After Cage, these ideas were – slowly but steadily – subsumed and assumed by the musical world, so that today graphical scores, verbal scores and the likes are commonly accepted as “other” forms of writing and composing music.

This may help us to make a further point, concerning how philosophical and aesthetical thought relates with music. We have just seen that Pollock had no control whatsoever (and did not want to have any control) on the final appearance of his works of visual art. If two adjacent balloons were filled, respectively, with green and red paint, the artist did not decide which of them should explode, and even less which shape would the spilled paint determine on the canvas. It was a matter of chance, depending on which balloon was hit. As said already, art was in the idea; the final visual appearance was almost an accessory.

This implies a disjunction between “body” and “mind” (or “soul”) which is rather typical for the modern era and determines a fracture, a hiatus, between this modern and postmodern concept and the one preceding it. Within a Christian concept of art, “body” and “mind/soul” are integrated, not in opposition; the “concept” behind Leonardo’s Monna Lisa and the visual appearance of the painting are not separable. Had Leonardo had the “concept” of the Monna Lisa painting but not the ability to paint it, that would not have counted as art. Had (per absurdum) a Pollock-style random pouring of paint on a canvas produced the Monna Lisa, that would also not have counted as art.

With Cage, the aesthetic perspective is similar, in the aural field. When the child Mozart was brought in the European Courts by his father, and asked to improvise on a given theme or freely, the idea was that the child Mozart was the genius, the artist, not those asking him to improvise. And, again, should a cat walking on a keyboard have produced the Jupiter Symphony, that cat would not have been considered as an artist of Mozart’s standing.

Cage, instead, contended – with his works of art – that the concept is what counts. And, furthermore, this has an even more dramatic impact on music than Pollock’s on visual art. In the end, in fact, a particular Pollock canvas does have a definite visual appearance. Although two “paintings” by Pollock may have been produced with the same technique, in the end their look is precisely defined, and an expert in Pollock’s works will be able to recognize, at sight, which painting is the one shown to him or her.

By way of contrast, not even the greatest expert of Cage’s music could recognize, upon hearing, a performance of some of his works as such. Two different renditions of Four6, for instance, will sound completely different, and it is practically impossible to identify them as performances of Four6, unless the listener has the score and a chronometer.

This is because the “score” of Four6 does not determine in the least the pitches, rhythms, sounds, durations, and not even the instrument or instruments that have to play.

Four6 belongs in a “numerous” series of pieces by Cage – “numerous” is in inverted commas because the series under discussion is made of many pieces, but also because those works are known as “number pieces”. Each of them has a title composed of two numbers, the first of which is written as a word, and the second as a digit. The first number indicates the number of players which ought to perform in the piece. Through the second number, Cage identifies how many pieces he had written, until a certain moment, for that number of players, in the series of “number pieces”.

Practically speaking, therefore, Four6 is a piece for four players, and it is the sixth Cage wrote for a “quartet” in the series of “number pieces”.

The work was first conceived in 1990, but Cage restructured it in 1992; it received its world premiere in the same year, on July 23rd, in New York, at Central Park Summerstage. It was the last public appearance of Cage, a mere fortnight before his death. The piece’s duration is 30 minutes: this is one of the very few detailed and prescribed elements of Cage’s “score”, as we will shortly see.

The volume containing the instructions for a rendition of Four6 contains in fact a verbal introduction, and some pages of “score” (whose visual appearance, however, would suggest to very few people the idea of a musical score).

Indeed, even the claim that Four6 is a piece for four players, as stated before, is misleading. Cage’s instruction, on the book’s first page, reads literally: “for any way of producing sounds (vocalization, singing, playing of an instrument or instruments, electronics, etc.)”. This implies that there should be four “layers”, each made of a different kind of sound production, but these need not necessarily be realized by four different players. For instance, a single performer could sing, produce other sounds with his or her voice, clap his or her hands, and rub a piano’s strings. This would actually count as a performance of Four6, but – at the same time – being a performance realized by a single musician, it would also count as a performance of One7, another “number piece” by Cage. Also the piece’s dedication mirrors this double titling and double destination: One7 is dedicated to Pauline Oliveros on her sixtieth birthday, while Four6 bears the same dedication but also adds Joan La Barbara, William Winant, and Leonard Stein (the performers of the world premiere).

The following instructions represent the remainder of the verbal component of Cage’s “score”: “Choose twelve different sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude, overtone structure, etc.). Play within the flexible time brackets given. When the time brackets are connected by a diagonal line, they are relatively close together. When performed as a solo, the first player’s part is used and the piece is called One7”.

In other words, the performers should elect and number twelve sounds. Then they can begin producing that sound at any moment within a “flexible time bracket” (i.e. a temporal indication with a chronometrical beginning and end), and finish that sound production similarly.

Thus, sounds superimpose, and can create something akin to “harmony” – the nemesis of avantgarde composers. Cage himself seemed to be surprised by this, as he stated in 1990 (i.e. in the year when Four6 was first imagined): “I’m surprised at almost all the ideas that come to my head, because they have to do with harmony”, he said.

Cage’s concept is echoed, and creatively answered, by Sergio Armaroli, who is featured in this CD not only as a performer, but also as a composer (given, and not granted, that these two categories can be applied to the repertoire under discussion). Structuring the Silence. Eight Part(s) has had an even longer gestation than Cage’s Four6, extending, as it did, over a period of seven years. It is scored “for solo, two, four, and more performers”, thus mirroring the utter freedom of Cage’s concept.

The first verbal instructions given by Armaroli are purposefully and remarkable similar to Cage’s, but also subtly different, as will be clear by reading them side by side: “Choose all different sounds with fixed characteristics (amplitude, tempo, overtone structure, duration, etc.) and nine elements: gestures, intention, words and other suggestion(s) etc. Durations and dynamics are free. The sounds to be made are long and short or very short. When performed as a Solo, for One Player, choose cymbals and/or drums”. The “score’s” following pages are made of time brackets (like Cage’s), but are divided by number of players – so there are instructions for one player, for two, etc.

Other instructions are given later, in Structuring the Silence. Erratum Version. Inside Outside (2018); here, the indications are tangibly different from Cage’s, even though the connection between the two composers remains clear and takes the form of a posthumous and explicit homage by the younger to the older musician. Other variants of Structuring the Silence take the name of “Habitat”; “for Angelica”; “Erbario sonoro”; “Extended (per Quattro | inResonance”; and “In the Garden (…nel Giardino)”, recorded here. Here the sounds to choose are nine or groups of nine. The allusion to the “garden” is explained later: “the tape “is the Garden”: any tape (of natural sounds or other: birds etc…) it must not be intended as a background but must have the same level of amplification (stereo or quadriphonic) of the instruments, mixing with the sounds of the environment in a single sound landscape: in resonance, in the quartet”. Further, resonance has a fundamental role, and basically structures the piece.

Thus, the crossing paths of Cage and Armaroli become the source of renewed, fresh creativity, in a productive interaction which involves virtually all kinds of sounds found in nature or artificially produced.

Chiara Bertoglio

![Rachael & Vilray - West of Broadway (Deluxe Edition) (2026) [Hi-Res] Rachael & Vilray - West of Broadway (Deluxe Edition) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769104420_cover.jpg)