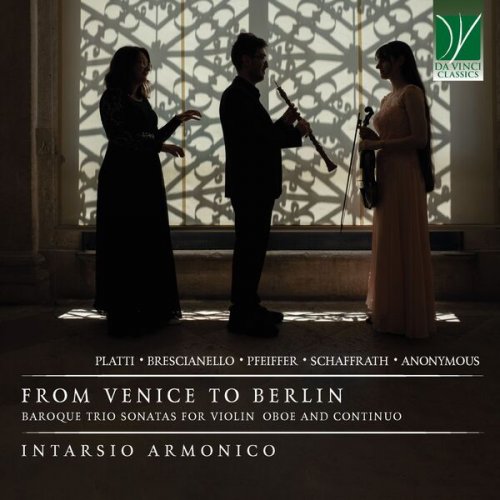

Artist:

Intarsio Armonico

Title:

From Venice to Berlin: Baroque Trio Sonatas for Violin, Oboe and Continuo

Year Of Release:

2024

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 59:06

Total Size: 353 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:1. Trio Sonata in D Major: I. [...] (For violin, oboe and continuo) (03:10)

2. Trio Sonata in D Major: II. Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (03:48)

3. Trio Sonata in D Major: III. Largo (For violin, oboe and continuo) (02:30)

4. Trio Sonata in D Major: IV. Non tanto presto (For violin, oboe and continuo) (02:47)

5. Trio Sonata in C Minor: I. Largo - Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (04:57)

6. Trio Sonata in C Minor: II. Adagio (For violin, oboe and continuo) (03:35)

7. Trio Sonata in C Minor: III. Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (04:47)

8. Trio Sonata in A Major: I. Adagio (For violin, oboe d'amore and continuo edited between 1710-1725) (01:56)

9. Trio Sonata in A Major: II. Allegro (For violin, oboe d'amore and continuo edited between 1710-1725) (03:21)

10. Trio Sonata in A Major: III. Adagio (For violin, oboe d'amore and continuo edited between 1710-1725) (01:25)

11. Trio Sonata in A Major: IV. Allegro (For violin, oboe d'amore and continuo edited between 1710-1725) (02:06)

12. Trio Sonata in C Minor: I. Gravement (For violin, oboe and continuo) (01:51)

13. Trio Sonata in C Minor: II. Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (01:31)

14. Trio Sonata in C Minor: III. Adagio (For violin, oboe and continuo) (02:50)

15. Trio Sonata in C Minor: IV. Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (01:55)

16. Trio Sonata in G Minor, CSWV E:18: I. Allegro (For violin, oboe and continuo) (06:07)

17. Trio Sonata in G Minor, CSWV E:18: II. Largo (For violin, oboe and continuo) (04:46)

18. Trio Sonata in G Minor, CSWV E:18: III. Presto (For violin, oboe and continuo) (05:35)

“From Venice to Berlin”. These two European cities are today, but have always been, worlds apart from each other. A city on the sea, actually “built” on the sea; projected into the Adriatic Sea, and having construed its wealth through commercial activities with the East, the Far East, but also in many other directions. And a city in the very midst of the European Continent, firmly anchored on the earth, with a thriving cultural life but markedly different from that of the Serenissima. A Republic ruled by Dukes; a monarchy whose ruler left always a mark on the lived experience of the citizens in his State.

Yet, in spite of the evident differences, there were also important connections between these two worlds. People travelled a lot in the Baroque era; ideas – and music scores – travelled with them. Venice had many connections with the territory of today’s Germany, through the Hanseatic cities, and culturally through the Leipzig and Frankfurt Book Fairs.

The German Baroque musical culture had been profoundly marked by the influence of Venetian music, starting with composers such as Schütz who had studied in Venice and had exported the Venetian late Renaissance or early Baroque style in their country. The Venetian style had then received quintessentially German traits, for instance when the Lutheran chorale had met with the polychoral style of the Venetians; but already with Orlando de Lassus, who was based in Munich, had the Italianate and Venetian culture penetrated the German-speaking lands.

In the mid- to late-Baroque era, the flow of musicians who emigrated from Venice and Italy to Germany (or who simply stayed there for a significant time), and of those who went South from the German lands in order to study with Italian musicians in the Peninsula increased steadily. Among the musicians represented in this Da Vinci Classics album, both Brescianello and Platti were Italian composers who emigrated to, and worked in, Germany. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that a copious number of their scores is now found in German libraries. Conversely, the two Sonatas by German composers recorded here, and that by the anonymous musician, are characterized by a fascinating commixture of timbres. This is a typical feature of the Italian Baroque, along with the tight interweaving of musical dialogues, still another idiosyncratic trait of coeval music.

Altogether, this Da Vinci Classics album contains two Italian Triosonatas, two by German composers, and one by an anonymous musician. Their scores are found in various sources. Platti’s Triosonata is currently in Private collection of Count von Schönborn-Wiesentheid; Brescianello’s work is found in the collection of “Schrank 2” in the Saxon State and University Library Dresden, where also the anonymous Triosonata is stored. This manuscript is in the handwriting of Johann Georg Pisendel, a great Baroque musician in turn, who copied it. In the same collection we find also Pfeiffer’s Triosonata, whilst that by Schaffrath is found in the Berlin Staatsbibliothek.

Of these Sonatas, some are in the typical structure of the Church Sonata, characterized by four movements, alternating slow and quick tempi (starting with a solemn, majestic, stately one). Church Sonatas are also typically marked by an abundant use of contrapuntal and fugato writing, with imitations and rich polyphony, especially in their quick movements. Other Sonatas are in three movements, anticipating the Classical style (not by chance, this is exemplified here by Christoph Schaffrath’s Sonata, written by the youngest among these musicians).

The year and place of Giovanni Benedetto Platti’s birth are unknown, and so is information about his family. However, from Platti’s death certificate we know that at the time of his passing, in 1763, he was 64. The scanty data we possess about his early life bring us to Venice, where we find people with his family name (and possibly himself) attested as musicians.

Later, similar to other Italian musicians, Platti moved to Northern Europe, and in 1722 we find him in the employ of a Prince-Bishop, i.e. Johann Philipp Franz von Schönborn, in Würzburg, where he would remain until his death. He married a local singer and had a large family, and, together with them, he occasionally moved for some stretches of time to Bamberg, where the court chapel was also required to perform.

Other members of the Schönborn family also valued and prized Platti; in particular, Rudolf Franz Erwein, who lived in Wiesentheid, was a passionate and accomplished amateur cellist. For him, Platti worked as a performer, arranger, composer, and also as an adviser. The collection, whence comes the Sonata recorded here, comprises approximately sixty unique exemplars of Platti’s manuscripts, among which 28 Concertos for obbligato cello, twenty triosonatas where the cello has a role as a soloist, and many other works including sacred compositions. He also wrote secular vocal works and a significant output of keyboard music.

Platti’s works, especially those for cello and for harpsichord, are pioneering examples of the genres they exemplify. In particular, Platti’s habit to consider the cello as a concertante, melodic instrument is very original and innovative, at a time when the cello was normally employed mostly as a continuo instrument. His style is characterized by a typically Italian melodic vein, which is joined with a more Northern interest and skill in contrapuntal and polyphonic, imitative writing. Platti thus represents a fascinating example of the encounter between Venice and Germany, here seen from the viewpoint of an Italian.

As concerns Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello, we do know the whereabouts of his birth (in Bologna, around 1690), but nothing is documented about his first musical studies. It is likely, however, that they took place in his very birth city, where bowed string instruments were highly prized and cultivated. In his youth, he spent some time in Venice, leaving the city on the lagoon following a call by the Electress of Bavaria. He remained in Munich just for about one year, leaving it for Stuttgart where he became a member of the Court Chapel of the Duke of Wüttenberg; already in 1717, he received there the title of Music Director and Concertmaster. In 1731 he was promoted to the rank of chapel master and, in 1744, he was further elevated to the title of “Oberkapellmeister”. (In this role, he would be succeeded by another Italian, Jommelli, after an intermission when this title was attributed to the German Holzbauer).

In his capacity, Brescianello worked actively for the revitalization of the local opera theatre; there, he contributed to the appointment of Riccardo Broschi as the court composer (Broschi was the brother of the famous castrato Farinelli). The theatre went through alternating stages of prosperity and straits, but Brescianello was always determined that it could have a place of prominence. His output has been recently explored and its appreciation, long overdue, has now become an acquired fact in today’s musicology. His style reveals the influence of Corelli’s Church Sonatas, and represents a significant example of the transition between Baroque and Classicism. His was an original personality in his own right, and, similar to Platti, attributed protagonist roles to the cello.

Court life was also the experience of Johann Pfeiffer, whose main instrument was the violin and whose musical activity took place primarily at the court of Bayreuth. There, he worked as a chapel master to Margrave Friedrich of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, where Pfeiffer was also in charge of the musical education of the Margrave’s wife, Wilhelmina of Prussia. For the aristocratic couple, Pfeiffer wrote a significant part of his compositional output: this component is characterized by a fascinating balance between musical originality and technical accessibility. Both Friedrich and Wilhelmina were good, albeit not outstanding, amateur musicians; Pfeiffer was therefore able to satisfy their musical demands without asking too much of their skill.

Pfeiffer had been born in Nuremberg and studied there under the guidance of several musicians, while, in parallel, pursuing an education in law in Leipzig and Halle. He was in Weimar, as a violinist in the court chapel in 1720, finding his new home in Bayreuth in 1732.

His compositional style mirrors the one prevailing in contemporaneous Germany, and reveals affinity with that by Telemann and even by Johann Sebastian Bach. He was also active as an operatic composer; his instrumental output, along with the “easier” works written for the noble couple, includes virtuoso works composed for his own use and that of his professional colleagues. He was highly appreciated by his contemporaries, as is witnessed by the large circulation of his works at his time. Unfortunately, this wide dissemination is not matched by a corresponding preservation of his works.

Last but not least, we encounter Christoph Schaffrath, who was primarily active at the court of Frederick II of Prussia. Scarce information survives about his early musical education, although some sources bear witness to his precocious talent at the keyboard. In his early twenties, Schaffrath sought fortune in Poland (Warsaw), where he performed the harpsichord in August II’s court orchestra. A few years later (1733) he moved to Dresden, where he was one of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach’s competitors for the post of organist at St. Sophia (Bach’s son was given the job). After a short intermission as a musician in the court orchestra of Elector Paul Charles Sanguszko, he is found in Berlin (from 1734) as a composer and harpsichordist at the Prussian Court. From 1741 he became the reference musician of the King’s sister, Anna Amalia of Hohenzollern.

He was also an appreciated music teacher, prized by his students, among whom are the castrato singer Felice Salimbeni, flutist Friedrich Wilhelm Riedt, and violinist-composer Johann Otto Uhde. He also wrote a treatise, bearing witness to his teaching and performing style.

His output, as far as we know, includes only instrumental music, which is preserved mainly at the Berlin Library; one of the main traits of his personality is his proficiency and skill in the treatment of counterpoint and imitative polyphony, at a time when rococo and Classical style were progressively eroding the primacy of these styles.

Together, these Sonatas open up a window toward the extraordinary international and cross-cultural experience of these brilliant musicians, whose connections with some of the most splendid German-speaking courts permitted the creation and dissemination of a transnational musical language.

![Martin Listabarth Trio - In Her Footsteps (2026) [Hi-Res] Martin Listabarth Trio - In Her Footsteps (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771946819_folder.jpg)