Artist:

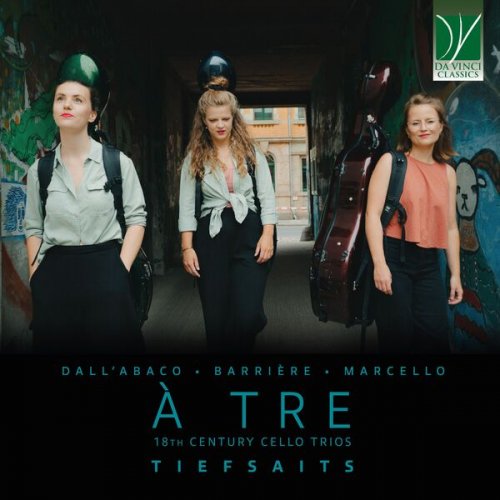

Ensemble Tiefsait

Title:

Dall'Abaco, Barrière, Marcello: 18th Century Cello Trios

Year Of Release:

2024

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 59:15

Total Size: 256 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:1. Trio No. 1 for three Cellos in B Major, ABV 54: No. 1, Moderato (06:16)

2. Trio No. 1 for three Cellos in B Major, ABV 54: No. 2, Adagio (04:50)

3. Trio No. 1 for three Cellos in B Major, ABV 54: No. 3, Capriccio (05:42)

4. Trio No. 1 for three Cellos in B Major, ABV 54: No. 4, Allegro (04:03)

5. Caprice No. 4 in D Minor (03:48)

6. Sonata No. 2 a Tre in D Minor: I. Adagio (Livre III) (01:42)

7. Sonata No. 2 a Tre in D Minor: II. Allegro (Livre III) (01:31)

8. Sonata No. 2 a Tre in D Minor: III. Aria - Largo (Livre III) (02:42)

9. Sonata No. 2 a Tre in D Minor: IV. Giga (Livre III) (02:04)

10. Caprice No. 1 in C Minor (03:10)

11. Sonata a Tré No. 2 in C Minor: I. Largo (04:27)

12. Sonata a Tré No. 2 in C Minor: II. Presto (02:33)

13. Sonata a Tré No. 2 in C Minor: III. Grave (01:24)

14. Sonata a Tré No. 2 in C Minor: IV. Presto (01:55)

15. Caprice No. 2 in G Minor (03:09)

16. Trio No. 2 for three Cellos in G Major, ABV 55: No. 1, Moderato (03:49)

17. Trio No. 2 for three Cellos in G Major, ABV 55: No. 2, Larghetto (02:46)

18. Trio No. 2 for three Cellos in G Major, ABV 55: No. 3, Comodo (03:15)

During the course of the 18th century the cello rose from a humble accompanying bass instrument to a full-fledged solo instrument in its own right. The bass violins around 1700 were rather large and unwieldy instruments which provided a good bass resonance. A smaller version of the bass instrument of the violin family called ‘violoncello’ came into existence in Italy during the last decade of the 17th century. Advances in string making, e.g. the invention of metal wound gut strings for the lowest string on the cello, facilitated smaller instruments sounding at the same pitch as the large bass violins. These new cellos were easier to play on and offered a different, more soloistic timbre, particularly in its higher tenor register. The first sonatas for cello, as well as chamber music with obligato cello parts, originated in Italy just before 1700. It was in the decades after 1730 that the cello experienced a meteoric rise all over Europe: there was a rapid development in playing standards and in public interest in the instrument. Cello soloists, as for example Salvatore Lanzetti (c1710–1780), Joseph-Marie-Clément Dall’Abaco (1710–1805), Johann Georg Schetky (1737–1824) and Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805), toured Europe giving solo concerts and performing cello concertos. The cello quickly became the instrument of choice for musical amateurs, too. In France, Michel Corrette’s (1707–1795) treatise in cello playing and more than 25 volumes of cello music by French and Italian composers, which appeared at the publisher Le Clerc in Paris between 1738 and 1750, testify to a burgeoning amateur market. In England, Peter Prelleur (1705–1741) added a fingering chart and two lessons for the cello to his music primer The Modern Musick-Master, published in 1731. A year later, Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, started to taking cello lessons and thus set an example for countless other noblemen and gentry in Britain and on the continent. This development of the cello as an instrument of the nobility was partly due to the advantageous playing position: the aristocratic cello player could sit on a chair while making music and avoid unbecoming contortions which the violin necessitated. The cello shared this feature with the viol and the wide-spread viol playing among noble amateurs facilitated switching to the cello once the viol became antiquated. Thus, the first English cello treatise, published by Robert Crome in London around 1765, could claim that ‘this instrument [the cello] appears to be built on the ruins of another, I mean the viol or six string’d bass, which in the last century was held in great esteem and of general use in concerts’ before stating that nowadays ‘the Violoncello is an excellent instrument, not only in concert, but also for playing lessons &c’.

It was in this context of a downright cellomania that the virtuoso cellist Giuseppe Clemente Dall’Abaco arrived in London in 1736. Dall’Abaco was born in Brussels in 1710. His father Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco (1675–1742), a cellist and violinist himself, was concert master at the Bavarian court who in 1710 was exiled in Brussels. Presumably, Guiseppe Clemente first studied the cello with his father. He was sent to Italy in his teens to further his musical education and, upon his return early in 1729, he petitioned in vain for a position at the Munich court orchestra. Instead, he was taken on by Elector Clemens August I (1700–1761) as cellist at the electoral court in Bonn in March 1729. Clemens August was an avid amateur musician and he played the cello and the viol himself. Dall’Abaco’s extended sojourn to England lasted at least from April 1736 until the end of 1737. He appeared on 15 April 1736 at Hickford’s Music Room in Brewer Street London and is documented to have arrived in York towards the end of 1737, assisting the local music assembly. Upon his return to Bonn Dall’Abaco was promoted to the post of director of the chamber music in 1738. He probably also visited Paris in the 1740s. His time in Bonn came to an abrupt end in 1753, when his brother-in-law escaped from the court with an immense amount of money. Adding insult to injury Dall’Abaco himself was accused to have plotted the murder of the Elector Clemes August. Even though he was cleared of all charges he left Germany and moved to Verona, his father’s place of birth. There, he spent most of his time at the country estate of his family just outside town and appeared only sporadically as a cellist in northern Italy. He died there aged 95 on 31 August 1805.

Dall’Abaco’s surviving compositions consist mainly of music for his own instrument, the cello: eleven caprices for cello solo, 35 cello sonatas for cello with continuo, three duos for two cellos and the two trios for three cellos, which frame the present recording. The opening piece of this CD, the trio in B-flat major, is a charming composition in four movements. It is exceptional in its handling of the three voices as truly equal partners, whereas all other trios on this recording present the traditional texture of a baroque trio sonata with two melodic voices and bass. The first movement highlights the cantabile quality of the cello with each voice taking turns to sing highly galant melodies, some of them rather upbeat and others more melancholic. The following Adagio mimics an opera scene: after an introduction of ten bars, which sets the stage for the heroine, the second cello intones an expansive heartfelt melody to the accompaniment of the other cellos. After a playful Capriccio the final Allegro presents a stylized minuet, a reminiscence of the baroque court within a thoroughly galant composition.

Whereas the trio was probably meant to be performed in concert, Dall’Abacos Caprices for solo cello were almost certainly music for his own private use or they might even be improvisations, written down afterwards. As James Grassineau (1715–1767) states in his Musical dictionary (London 1740): ‘CAPRICIO means Caprice, the term is applied to certain pieces, wherein the composer gives a loose to his fancy, and not being confined either to particular measures or keys, runs divisions according to his mind, without any premeditation; this is also called Phantasia.’ The three Caprices recorded on this album, all written in minor keys, certainly testify to this fantastical aspect of a Caprice. They present the listener with an enormous range of expression: there is the agitated, troubled Caprice No. 2 in g-minor, the pensive Caprice No. 4 in d-minor and the Caprice No. 1 in c-minor full of dark melancholy.

Jean-Baptiste Barrière (1707–1747) was the foremost French cellist of his generation. He probably was born in Bordeaux and moved to Paris before 1730. In 1733 he was granted a privilege to publish instrumental music for six years. His first two books of cello sonatas appeared in 1733 and 1735. He went to Italy in the following years and the advertisement for his third book of cello sonatas, published in Paris in 1739, mentions him as having recently returned from Italy. Barrière’s printing privilege was renewed for another 12 years and he issued at least three further collections of instrumental music: another book of cello sonatas, a collection of sonatas for the pardessus and one for the harpsichord. Barrière might have started off as a viol player in his youth and his first book of cello sonatas is a fascinating attempt to continue the music of the great French viol tradition on the cello. In contrast the music in books 3 and 4, published after his Italian journey, reflects his absorption of the style of contemporary Italian sonatas. It is within book 3 that we find the Sonata II. a tre, which is included on this recording. Already in Barrière’s first collection of cello sonatas there are many instances of the bass part splitting into two separate lines for the continuo cello and for the harpsichord, but the present composition is a fully-grown trio sonata for two obligato parts and bass. The upper part is notated in the g-clef, which might imply a violin or a pardessus de viole, yet it was also customary to read the g-clef an octave down and to play these parts on the cello. On this recording tiefsaits are using a small French 5-stringed cello with an additional e-string for the upper voice, which provides a special, silvery timbre. The first movement, Adagio, is in fact a very French prelude reminiscent of older viol music. The elegant Allegro exhibits Italianate imitation between the parts and exploits the rich sonority of the three instruments in the bass-tenor-range. The third movement Aria Largo is a wonderful re-interpretation of an Italian Siciliano in a French cloak: rhythm and metre of the melodic lines are perfectly Italian whereas the rondeau form and the sonority revert to French traditions. The Sonata a tre closes with a joyful hunting party in form of a Giga.

Benedetto Marcello (1686–1739) was born in Venice, a generation before Dall’Abaco and Barrière. In contrast to the other two composers on this recording, Marcello was not a professional cellist. He was not even a professional musician but a true ‘amateur’ in the 18th-century sense of the word: this did not imply any judgement on Marcello’s skills as composer and musician but it simply meant that he was not dependent on music for his income as he followed a career in the legal profession. Marcello attained pan-European fame as a composer and was admired for his instrumental music, in particular for his psalm settings in the style of cantatas. His collection of six Sonata a Tré was issued around 1736 in Amsterdam by the publishing firm Witvogel. It is the first printed collection of trio sonatas for two cellos and bass and bears witness to the soaring popularity of the cello at that time (although the title page also provides an alternative scoring with two viols on the top parts). In Italy the trio sonata for two violins and bass was the quintessential chamber music formation of the time and here, in Marcello’s compositions, the violins are replaced by cellos. The first movement of the Sonata II revels in this new and unheard-of sonority, which is heightened by the warm and dark colour of the key c-minor. The following Presto livens up the proceedings: written in stile antico the upper voices appear in constant imitation of each other, exchanging fast and eloquent musical figures. The third movement, Grave, transforms the restless energy of the previous movement into a moment of noble, upright calmness in the golden resonance of the parallel key E-flat major. The movement ends on a half close, which leads into an astonishing final Presto. Having two movements headed Presto in the same sonata is quite unusual in itself. Yet, this movement eschews all convention by dropping the bass line and, even more so, by the manner in which the upper voices are set: there is actually only one erratic melodic line left in the movement with the second cello throwing in canonic imitations of musical fragments.

With the final work on this recording, we return to music written by Guiseppe Clemente Dall’Abaco. The texture of his Trio in G-major resembles Marcello’s trio sonatas with two cellos as melodic upper voices, while the third cello mainly provides the bass. Yet, contrary to Marcello’s works, the two melodic lines in Dall’Abaco’s composition require virtuoso performers with high passage work in thumb position and cantabile melodies. A galant conversational Moderato as first movement is followed by an immensely beautiful Larghetto in 6/8 with long singing lines and elegant turns. The final movement Comodo is enlivened by a continuous quaver movement in the bass, while the top parts perform highly virtuoso figures and gestures leading into a final stretta which takes the first cello up rising to its highest note g’’ in the penultimate bar.

Listening to this album of baroque cello trios by three fascinating composers, it is easy to agree with James Grassineau, who states in his musical dictionary: ‘TRIO, is said of a piece of music made to be performed by three voices; or more properly a composition consisting of three parts only. […] Trios are the finest kinds of composition.’

Viktor Töpelmann © July 2024

![Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res] Noga - Heroes in The Seaweed (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771663366_nhs500.jpg)