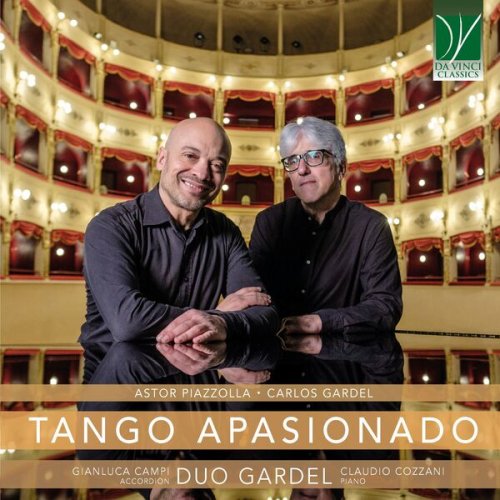

Duo Gardel - Piazzolla, Gardel: Tango Apasionado (2025)

Artist: Duo Gardel

Title: Piazzolla, Gardel: Tango Apasionado

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:04:49

Total Size: 315 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Piazzolla, Gardel: Tango Apasionado

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:04:49

Total Size: 315 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Milonga for Three

02. Meditango

03. Violentango

04. Sus ojos se cerraron

05. Volver

06. Oblivion

07. El dia que me quieras

08. Por una cabeza

09. Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: No. 1, Otoño Porteño

10. Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: No. 2, Invierno Porteño

11. Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: No. 3, Primavera Porteña

12. Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: No. 4, Verano Porteño

13. Libertango

The story narrated in this Da Vinci Classics album is a story of immigration, of families, of music, of friendships, and, of course, of tango. Besides the two performing artists, there are two acknowledged protagonists, i.e. Carlos Gardel and Astor Piazzolla, who are rightly considered as the greatest composers of tango music in the first and second half of the twentieth century respectively. These two musicians are united not only by their talent and by tango, but also by their brief cooperation and the reciprocal esteem they always demonstrated.

The older of them was Carlos Gardel. He was born in France on December 11th, 1890, in the city of Toulouse. His original name was Charles Romuald Gardès; Gardès was his mother’s family name. Young Berthe, twenty-five, had conceived Charles with a married mano who did not recognize the child. Berthe, a simple laundress, had soon to leave her city, and later the country and Europe, in order to write a new, different future for herself and for her child. They eventually landed in Buenos Aires when the child was about two and a half years old. Berthe fashioned herself as a widow, in order to accrue the social respectability of the small household. While she worked intensely to support her child, Charles grew up in the streets of the city; his first language was to be Spanish, and the other children would call him “the little French boy”.

He left his formal schooling rather early, when it became clear that his greatest talents lay in the musical field. In particular, he had a sensational voice, as a baritone/tenor, and also very promising looks, even though he had to remain on a semi-permanent diet in order to lose a conspicuous part of his weight.

His singing career took off with bars, clubs, and salons, but soon he began to be appreciated in larger halls, becoming a very successful recording artist and an idolized movie actor. In parallel with his multifaced activity as a performer, Gardel (who by then had changed his first name from Charles to Carlos, and his family name from Gardès to Gardel) became also a very appreciated composer. In particular, he soon found that the field in which his music could really excel was that of tango music.

And tango music was precisely the link connecting him with his younger colleague, Astor Piazzolla.

Piazzolla was born thirty-one years after Gardel – i.e., one generation later. Although Astor was born in Argentina, he too came from a European family; in his case, his parents and grandparents were Italians, respectively from Central (his mother’s family) and Southern Italy.

But just as Gardel had left Europe as a toddler, similarly Piazzolla remained in Argentina just for the first three or four years of his life, before returning to it multiple times in the course of the later years. In 1925, his family moved to New York, where they settled in the Greenwich Village. There, the child was exposed very soon to a variety of musical forms: the budding jazz culture of the Roaring Twenties, but also the traditional musical heritage of Argentina, as well as Western Classical music, in the disks owned by his father. It was also from his father that Piazzolla received his first musical instrument, a bandoneon (a kind of accordion) which the boy learnt to play spontaneously, by observing and studying what his father did with his own instrument.

It soon became clear that Astor had a particular gift for music, and he took music lessons – always in an informal, but yet very solid fashion – with some important musicians. Playing technique was taught to him by a Hungarian pianist, Béla Wilda, who had studied with legendary Sergei Rachmaninov. It was precisely at that time, in the mid-Thirties, that Gardel and Piazzolla met. Gardel invited Piazzolla to play with him extensively; their cooperation extended to one of Gardel’s most celebrated movies, El día que me quieras, in which young Piazzolla also plays, as a newspaper boy who appears in a cameo. Songs featured in this movie include many of Gardel’s most successful ones, such as the one which lends its title to the movie (“El día que me quieras”), sung by Gardel with Rosita Moreno; “Sus ojos se cerraron”, and “Volver”. All three are tangos (while other songs in this movie are country songs, waltzes, or rumbas). And all three also appear in the album we are about to listen.

It seemed established that a great friendship and cooperation would develop among the two musicians, sealed by the older one’s invitation to the younger one to accompany him on a concert tour. As is easily imaginable, the teenager Piazzolla was thrilled by that perspective; it is also easy to imagine that he was highly disappointed when his father – who would later be immortalized by the famous tango Adios Nonino – forbade him to accept Gardel’s invitation, on the ground that the boy was still too young. This seemingly harsh prohibition was to be an act for which Piazzolla would remain grateful to his father all his life. Gardel, with the musicians who had accompanied him, was to die tragically and prematurely precisely on that occasion, in a crash between two planes.

The young man’s career started to develop; very cleverly, however, Piazzolla was able to pursue in parallel both his budding career and his studies. Some of his teachers were among the greatest musicians of his era; furthermore, Piazzolla eagerly studied the works of musicians who could not directly teach him (among them, to cite but two, Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel). Moreover, his attention was always divided between classical music (including “modern classical” music), jazz, and traditional Argentinian music. Among his mentors were Alberto Ginastera, composer and pianist, whose teaching had been recommended to Piazzolla by Arthur Rubinstein.

This background was to prove Piazzolla’s most original trait, but also the most controversial one; and whilst the true appearance of his tango nuevo would manifest itself some years later, his first experiments in musical innovations were already worrying many musicians with whom he had cooperated until then. It became clear that Piazzolla had to manage an orchestra or ensemble of his own if he wanted to delve deeper into the potential of a new musical style associated with traditional tango but also distinct from it. In particular, just as Bach (and others) had disenfranchised the stylized dances of the Baroque suite from actual dancing, and turned them into pieces “to be listened to”, similarly did Piazzolla try (and succeed) to free the tango from his status as a background to dancing, and to turn it into a concert genre.

The road to that was to be very long, though. Whilst already in 1946 did Piazzolla found the first orchestra of his own, four years later he faced a deep crisis. The orchestra was dismantled, and the musician was tempted to forsake entirely the genre of tango music. He was increasingly attracted by jazz, and his works of the early Fifties are highly experimental. Wishing to further his musical experiences, he courageously took a major step: he crossed the Atlantic, and went to study with legendary composer Nadia Boulanger. Piazzolla, in awe before her, and fearing that his Argentinian background would have compromised his “seriousness” as a composer, offered her first his most avantgarde compositions. However, it was only when he eventually displayed his tangos to the teacher, that she became truly enamoured with his talent and manifested her enthusiasm for him. She did help him to perfect and polish his compositional style in the Western Classical tradition, but, at the same time, urged him to walk his own, unique path, in the blend between that and tango music.

From that moment, Piazzolla’s life and career changed entirely. He was to found a long sequence of ensembles, with various settings; the most successful of them was probably the quintet. In these ensembles, a variety of instruments, from a variety of provenances, could find their place. Scandalizing tango purists, he was to admit instruments from the classical tradition, from the world of jazz, but also from the new worlds of electronic music or even of rock music. A similar scandal, it has to be said, was to ignite among Classical music purists, who were analogously outraged by the presence of bandoneons and tango music in the temples of Classical music.

In spite of all this, Piazzolla quickly established his name as a very innovative voice in the panorama of twentieth-century music. He lived on both sides of the Atlantic (also due to the political situation in his country) and gained reputation worldwide. A nation which welcomed him with particular enthusiasm – possibly also due to Piazzolla’s roots there – was Italy, where Piazzolla cooperated with some of the most important musicians of the era (including Mina, Milva, or Tullio De Piscopo) and where he created and recorded Libertango.

This tango, one of the most celebrated of his output, was also to become a protagonist of numerous movies, and was to be remixed or reinterpreted by countless artists. However, along with this, Piazzolla was to write or compose approximately 3,000 works, a sixth of which were recorded by him.

Some of his most prestigious cooperations include that with Jorge Luis Borges, probably the greatest writer of his country, and with immense cellist Mstislav Rostropović; Piazzolla also wrote an opera, María de Buenos Aires, and constantly referred to the musical tradition of the past. His Estaciones Porteñas, recorded here, are an explicit homage to Italian Baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi, but allusions to musicians throughout the history of music punctuate his output.

The works recorded here, therefore, constitute a kind of Histoire du tango, borrowing the title from one of Piazzolla’s famous compositions. A history written by genius musicians such as Gardel and Piazzolla, but a history to which also the humble, unpretentious contributions of anonymous, unnamed musicians are integral components. And both Gardel and Piazzolla would have been glad to acknowledge this.

![Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden & Ed Blackwell - Old And New Dreams (1979/2025) [Hi-Res] Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden & Ed Blackwell - Old And New Dreams (1979/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766322079_cover.jpg)

![Mick Rossi - Songs from the Broken Land (2024) [Hi-Res] Mick Rossi - Songs from the Broken Land (2024) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766399499_592x592.jpg)