Gregorio Fracchia - Nodi quasi di stelle: Composer-Guitarists and Harmonizations of Traditional Songs (2025)

Artist: Gregorio Fracchia

Title: Nodi quasi di stelle: Composer-Guitarists and Harmonizations of Traditional Songs

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:48:27

Total Size: 205 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Nodi quasi di stelle: Composer-Guitarists and Harmonizations of Traditional Songs

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:48:27

Total Size: 205 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Mythology

02. Come le farfalle

03. Tempo di tarantella -da Acquarelli napoletani-

04. Preludio da Fantasia sul nome di J.S. Bach

05. Dance da Moments live in my memory

06. Notturno, No. 1

07. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 1, A Vucchella

08. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 2, L’aniello

09. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 3, Fenesta Vascia

10. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 4, Funiculì funiculà

11. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 5, La Luisella

12. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 6, Graziella

13. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 7, Michelemmà

14. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 8, Santa Lucia

15. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 9, Tu ca nun chiagne

16. Canzoni Napoletane: No. 10, Il saltimbanco

17. Spanish Capriccio

18. In C

19. El Diablo Suelto

20. Alma Llanera

This work seeks to revive a particular approach to guitar playing which, while deeply rooted in folk music, reinterprets and renews it through the technical nuances of the instrument and a poetic vision grounded in the Segovian tradition. Odd as it may seem, nearly all the pieces included on this album reflect stylistic elements characteristic of Segovia’s school: think of the late-Romantic vibrato, the melodic lines carried on the inner strings, the portamenti, and the highly musical distribution of accents.

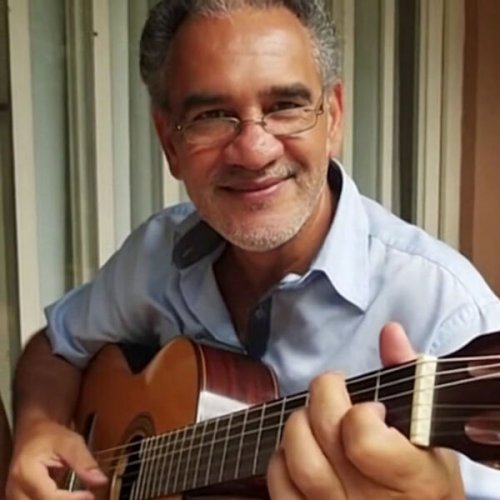

Many of these traits can be found, for example, in Alirio Díaz’s arrangements of Neapolitan songs—here recorded for the first time. This represents a complex and varied effort to enhance the popular Neapolitan repertoire, continuing Díaz’s lifelong mission to bring folk songs into the realm of classical guitar music. Indeed, this endeavor lies at the heart of Díaz’s own creative expression. As an arranger, he demonstrated his refined musical taste, profound and fertile understanding of harmony, and an instinctive, extraordinary ability to harness every potential of the guitar—including its most hidden and unexplored aspects. These arrangements could, in fact, teach today’s “pop” music the noble meaning of the word popular in musical terms.

This significant focus on folk repertoire by an interpreter like Alirio Díaz should not, however, be mistaken for a lack of proficiency in performing classical repertoire. Díaz, in fact, represents a truly unique case of all-encompassing musicality. His profile is equally versatile in the transcription of Renaissance and Baroque works as it is in the vibrant and deeply original revival of the music of his homeland. Moreover, in his transcription work of Renaissance and Baroque pieces, he carries forward a creative attitude that emerged not only with Segovia, but also with Regino Sainz de la Maza—his teacher in Madrid—who was active both in transcription (one need only think, among many, of his transcriptions of Sanz, Scarlatti, and Bach) and in harmonization of folk songs, as exemplified by the Canciones Castellanas.

Equally significant is another exploration of folk-inspired musical production: the compositional work of Maurizio Colonna. Here, his music is presented in direct continuity with Díaz’s creative world—as a natural evolution of it. In pieces such as Spanish Capriccio, Colonna not only showcases his undeniable virtuosity, but also inaugurates a new dimension in the relationship with the instrument, a direction consistently developed throughout his compositional output. His style is not foreign to harmonic experimentation or to the exploration of the guitar’s most intimate expressive realms, as evidenced in Notturno No. 1. This piece rivals the most renowned tremolo compositions for guitar—perhaps even surpassing them in its expansion of left-hand positions and use of the instrument’s full timbral range through the tremolo technique. This rare versatility of Colonna—which also echoes the multifaceted personality of his mentor, Alirio Díaz—is likewise evident in his activity as a performer-composer. A notable example of this is his collaboration with Australian guitarist Frank Gambale, in which diverse musical genres interact and blend with singular effectiveness, without either musician ever compromising their stylistic identity or losing the distinctiveness of their instrument.

From this alone, one can sense that the album presents a panorama of artists who have approached folk music in an unusual way, rediscovering its inherent harmonic, timbral, and expressive potential, and translating it into a profound, refined, never banal aesthetic language. This language, in turn, channels itself into the most noble and sophisticated tradition of classical guitar—an instrument that has never shied away from contact with “light” music, at least in the sense that mutual respect has long existed between classically trained musicians and those who grew up under the influence of another—but no less formidable—culture, one that blossomed in the streets of Spain, Latin America, and southern Italy.

It is enough to recall that Segovia, speaking of flamenco, often praised its nobility (a term that recurs frequently in these reflections), in contrast to the commercialization of flamenco that was already underway. And it is worth noting that the first composer to write for Segovia’s guitar was Federico Moreno Torroba, author of the famous Sonatina much admired by Ravel, and that Moreno Torroba also composed a magnificent concerto for flamenco guitar and orchestra, which Sabicas recorded under his direction.

All of this brings us to the meaning behind the title of this recording project: Nodi quasi di stelle (“Knots almost of stars”). The expression comes from La Ginestra by Giacomo Leopardi—one of the most extraordinary works of Western culture, radiating a deeply philosophical meaning that remains largely unexplored, though recoverable from Leopardi’s entire oeuvre—and must be understood outside its original context, simply as a synonym for constellation. Each musician woven into the album’s structure is like an artistic constellation, translating into a unique musical fabric that ranges from the cultivated to the popular, but which ultimately ties the various traditions into a complete, coherent organism, where music resounds seamlessly without interruption. This reinforces the idea that great creative minds are not confined to watertight compartments, as if a great folk musician could remain unaffected by the classical tradition, or vice versa. On the contrary, the leading performers and composers of the last century often engaged with the “other side” of musical production: emblematic examples include Horowitz’s admiration for Art Tatum and his desire to transpose Tea for Two to piano (a similar endeavor was pursued by Shostakovich), or Art Tatum himself reinterpreting Dvořák. One could go on, citing Benedetti Michelangeli’s passion for jazz (evident even in his pianism, especially in his unsurpassed early recording of Ravel’s Concerto in G) and for Oscar Peterson, or Heifetz performing Gershwin (and Gershwin seeking lessons from Ravel); or again, Alfredo Casella’s quotation of Funiculì Funiculà in Italia, to name but a few.

My compositions aim to enter this musical domain shaped by the aforementioned artists, extending—rather than departing from—the interpretive tradition begun by Tárrega and Segovia, and further developing it.

Finally, worthy of note is Tempo di Tarantella by Carlo Cammarota, taken from Acquarelli napoletani (Neapolitan Watercolors). This piece, once again, could easily sit alongside the works of Torroba or Turina. It accomplishes the difficult task of exploring harmonic innovation without falling into the all-too-common disdain for tradition—a disdain often voiced by musical languages that later dried up, proving far less vital than the tradition they sought to critique. Here too, Cammarota—like the composers Segovia involved in the great modernizing of the classical guitar—belongs to the realm of refined music, but not to the cerebral (concept-heavy and often unsuccessful) kind. At the same time, he pays true homage to folk music.

Ultimately (one hopes), it is folk music that clearly resounds throughout the repertoire selected for this work, and in the very aesthetic identity of the guitar—an instrument that, across the centuries, has continually reinvented itself while always retaining its ambiguous nature, suspended between the cultivated and the popular. (But what is culture, if not the illumination of a meaning we all already possess?)

![Clifton Chenier - Bon Ton Roulet! (1967) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Bon Ton Roulet! (1967) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/a5svymspyands9f5esq020o3f.jpg)

![Frank Sinatra, Count Basie - It Might As Well Be Swing (1964) [2021 SACD] Frank Sinatra, Count Basie - It Might As Well Be Swing (1964) [2021 SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766090910_scan-1.jpeg)

![Clifton Chenier - Squeezebox Boogie (1999) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Squeezebox Boogie (1999) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/cmlfho2wfdjon4pewnwrm16l7.jpg)

![Clifton Chenier - Classic Clifton (1980) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Classic Clifton (1980) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/7uht6cuaz3rb4d8ybfskyckea.jpg)

![Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res] Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/cn1c8l2hi7zp9j05a5u7nw49g.jpg)