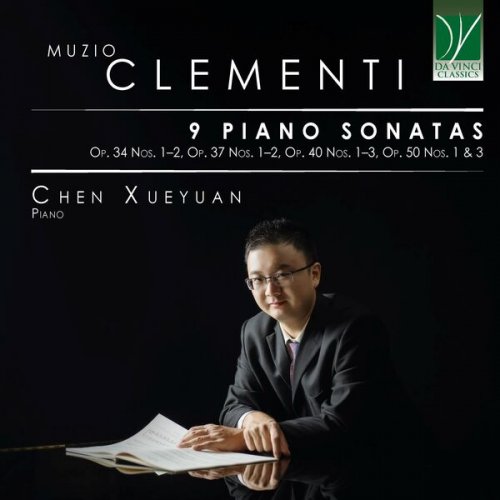

Chen Xueyuan - Muzio Clementi: 9 Piano Sonatas (2025) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Chen Xueyuan

Title: Muzio Clementi: 9 Piano Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 02:32:54

Total Size: 510 mb / 2.02 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Muzio Clementi: 9 Piano Sonatas

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 02:32:54

Total Size: 510 mb / 2.02 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 34 No. 1: I. Allegro con spirito

02. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 34 No. 1: II. Un poco Andante quasi Allegretto

03. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 34 No. 1: III. Allegro

04. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 34 No. 2: I. Largo e sostenuto

05. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 34 No. 2: II. Un poco adagio

06. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 34 No. 2: III. Molto allergro

07. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 37 No. 1: I. Allegro di molto

08. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 37 No. 1: II. Adagio sostenuto

09. Piano Sonata in C Major, Op. 37 No. 1: III. Vivace

10. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 37 No. 2: I. Allegro

11. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 37 No. 2: II. Adagio-In the solemn style

12. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 37 No. 2: III. Allegro con spirito

13. Piano Sonata in B Minor, Op. 40 No. 2: I. Molto Adagio e sostenuto

14. Piano Sonata in B Minor, Op. 40 No. 2: II. Largo, mesto e patetico

15. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 40 No. 1: I. Allegro molto vivace

16. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 40 No. 1: II. Molto adagio, sostenuto, e cantabile

17. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 40 No. 1: III. Allegro-Canon

18. Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 40 No. 1: IV. Presto

19. Piano Sonata in D Minor, Op. 40 No. 3: I. Molto Adagio

20. Piano Sonata in D Minor, Op. 40 No. 3: II. Adagio con molta espressione

21. Piano Sonata in D Minor, Op. 40 No. 3: III. Allegro non troppo

22. Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 50 No. 1: I. Allegro maestoso e con sentimento

23. Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 50 No. 1: II. Adagio sostenuto e patetico

24. Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 50 No. 1: III. Allegro vivace

25. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 50 No. 3 Didone abbandonata: I. Largo patetico e sostenuto-Allegro, ma con espressione

26. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 50 No. 3 Didone abbandonata: II. Adagio dolente

27. Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 50 No. 3 Didone abbandonata: III. Allegro agitato, e con disperazione

With this Da Vinci Classics album the listener is invited to enjoy some of the most interesting among the more than hundred piano Sonatas composed by Muzio Clementi, on whose gravestone the following words are inscribed: “Father of the Pianoforte”. It is impossible to grasp the seismic shift which led from the predominance of the harpsichord to that of the piano without giving Clementi his due. And, sadly, this is not frequently done.

Clementi is in fact a pivotal figure in the history of music, and in particular in the history of the piano, as well as a great artist in his own right. And yet, neither his historical significance nor his artistic worth are sufficiently recognized, beyond the somewhat restricted circle of the specialists.

Clementi was considered as one of the great musicians of his era by Ludwig van Beethoven, who recommended his works to his students and to his own nephew Karl. Mozart had a different opinion of him, but it has been argued – with some right – that Mozart’s evaluation might have been flawed for different reasons. Certainly, however, Clementi was held in high regard by his contemporaries, and his influence has extended well beyond his time, fostering the crucial transition between the keyboard technique of the Baroque and Classical-era harpsichord and the Romantic piano.

Clementi, whose grand first name was a direct reference to Classical Rome, was a typical child of the urbs caput mundi. He received his first musical education as a child, and he quickly became an appreciated organist and composer; he wrote his first large-scale work, an oratorio, at the extremely young age of 11.

His life changed rather abruptly when he was heard playing by an English nobleman, Sir Peter Beckford, who was visiting Rome and was highly impressed by the child prodigy. Beckford agreed with Clementi’s father that the boy would follow him in England. The baronet was to pay for his musical education until he reached the age of 21, while the young musician, in exchange, would provide musical entertainment for his family and the visitors of his estate.

Thus began Clementi’s life in Britain, and also a period of extremely intense study, where he developed his compositional and performance technique to a hitherto unknown level. The true “teachers” with whom Clementi studied in those years were the great masters of the recent past, from Johann Sebastian Bach to Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti. Indeed, Clementi would later create an instructive edition of some Scarlatti Sonatas which is the first known example of instructive editing. And the brilliant, transcendental technique of his fellow countryman Scarlatti would become the starting point of Clementi’s own sensational technique. Thanks to the relentless and tireless practice of his first English years, Clementi was to become an unequalled wonder at his times.

Once he reached his 21st birthday, Clementi left Sir Peter and embarked in a brilliant career, working at first in London, where the possibilities of making himself known were numerous. Furthermore, Clementi promoted his activity also thanks to the publications he issued, which won to him the favour of many musicians.

Later, he would return to the Continent, touring extensively many European countries and obtaining the praise of numerous colleagues as well as of the VIPs of his era. Among these was the Emperor who, in Vienna, challenged Clementi to an epoch-making musical “duel” with Mozart who was Clementi’s junior by a few years. (However, Mozart died at a much younger age than Clementi: impressively, one of Clementi’s children would be still alive in the twentieth century, thus spanning some of the most turbulent periods in the history of music with their lifetimes).

The “duel” with Mozart left mixed feelings in the audience. Only years later would the Emperor affirm that Mozart had left a more lasting impression on him. However, at the moment of its happening, the challenge did not have a clear winner, and the sum of money prepared by the sovereign was equally divided between the two artists. Mozart wrote disparagingly about Clementi to his father Leopold, but perhaps he admired Clementi more than he avowed. The theme of the Sonata played on that occasion by the Italian composer would feature prominently in the Overture from Mozart’s Zauberflöte, with Clementi hastening to add on every subsequent published edition of his own Sonata that it had been created ten years before Mozart’s masterpiece! However, Clementi did not bear a grudge against Mozart, and even transcribed that same Overture for solo piano.

But Clementi did not limit himself to playing. And not even to composing, which was a very important aspect of his life. He was an extremely appreciated teacher, and the impressive collection of the Gradus ad Parnassum (a hundred Etudes of noteworthy difficulty) bears witness to the completeness and thoroughness of his approach to the keyboard.

His activity, however, extended even beyond this. He had an initially very successful business of pianos; the one he sent to Beethoven would mark a deep “revolution” in Beethoven’s own concept of pianism, as is demonstrated by the piano Sonatas he was to write after the instrument’s arrival.

However, a disastrous fire burnt Clementi’s instruments, resulting in a huge economic loss (40,000 £, so it is reported). A catastrophe which would have destroyed many other people both psychologically and financially, was however not enough for stopping the volcanic personality of the Roman musician. Within a short space of time, he was active in the domain of music publishing; and he managed to secure for himself the rights in England of Beethoven’s works, which became famous in England also thanks to his promotional activity. Music publishing became increasingly important for him, to the point that Clementi decreased the number and frequency of his public appearance, leaving time for editing and publishing (indeed, Clementi has been charged with the allegation of modifying some of Beethoven’s harmonies in his publication of the Viennese master’s works).

The Sonatas recorded here bear witness to the variety of Clementi’s inspiration and to his undoubted talent. Allegedly, the first of the op. 34 Sonatas had been initially conceived as a Concerto (surprisingly, Clementi wrote just a single Piano Concerto, as far as we know), while the second had been created as a Symphony. If this was the case, Clementi was particularly skilled in transforming these works into “true” Piano Sonatas, which do not reveal by any of their elements the fact that they may have been transcribed after other genres of pieces.

Within the first of these two Sonatas, an especially remarkable piece is the lyrical second movement; here, the Clementian roots of the Nocturnes by John Field are evident, thus projecting Clementi’s influence – through his student Field – toward the pure Romanticism of Chopin’s own Nocturnes.

Somewhat reminiscent of the style of French Overtures is the G-minor Sonata, op. 34 no. 2, with a slow, solemn beginning followed by a masterful fugato piece; the alternation of the contrasting sections makes this piece a precursor of some of the most original and famous among Beethoven’s Sonatas. It is a Sonata which hints to a cyclical concept – although not fully developed – with the return of allusions and references to the first movement in the third. They frame a meditative and tranquil, barcarolle-like movement with more expansive episodes.

These two grand Sonatas are followed, in Clementi’s catalogue, by his best-known (and perhaps also least loved) compositions: the six Sonatinas op. 36 which are the daily bread of most budding pianists. It should be said that they are excellent teaching material, though perhaps not revolutionary (and for this they have been mercilessly scourged by the sarcasm of Erik Satie). The Sonatinas op. 37 are more complex and demanding than op. 36, and can be defined as true Sonatas. The first Sonata of op. 37 takes off with a theme which is suggestive of bucolic atmospheres; the second movement is almost a study in ornamentation (which is also highly valuable as a testimony of performance practice). The imitation of bagpipes resurfaces in the third movement, prompting a critical observation in a review published on the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. In fact, this trait is also found in the opening movement of the second sonata, where it is followed by a solemn sarabande-like slow movement and by a brilliant, easygoing Rondo. One of the most interesting pieces of this trio of Sonatas is the second movement of the third Sonata, which reveals, in its rigorous polyphony, the influence of Bach on the Italian composer.

The Sonatas of op. 40 represent a noteworthy change in Clementi’s style, corresponding to what Nikolaus Harnoncourt called “the 1800 watershed” in music composition and in the notational habits of the composers. It is possible that Clementi wrote them especially for John Field, with whom he was touring Continental Europe at the time. The first of these Sonatas is exceptional inasmuch as it is the first where Clementi employs four movement; however, instead of the Beethovenian Scherzos, here the added movement is an exercise in rigorous counterpoint. The opening movement of this Sonata is a brilliant piece with a symphonic conception; the slow movement is an ornate song with cascades of embellishments. The same penchant for the minor keys is also found in the twin Sonata op. 40 no. 2, whereby pathos and drama are achieved by prefacing the two large-scale, Sonata-form movement with slow, sad, and melancholy introduction. Here too a fascinating cyclical concept surfaces. And the same idea of the slow introduction seems to be resumed and expanded in the Adagio con molta espressione in D minor which is found at the heart of op. 40 no. 3. It paves the way for the finale, where extended canonic ideas intertwine with light-hearted images.

This album closes with two of the three op. 50 Sonatas, which were published late in Clementi’s life but were likely intended as twins of op. 40. The first of these Sonatas is generally spirited and luminous, as was typical for Clementi’s works in A major, although darker, even gloomy passages are also present, as is the pervasive polyphonic writing. The best-known of these (and perhaps of all of Clementi’s Sonatas) is however no. 3, called Didone abbandonata in an exceptional occurrence of program music within Clementi’s instrumental output. Most striking is the Largo patetico, but all movements constitute various declinations of the feelings of sadness, desperation, and grief.

Together, these Sonatas are a living witness to their composer’s talent, expressiveness, brilliant inspiration, and adroit skill in the handling of the musical material.

![Paul Mauriat - Après toi (1972) [Hi-Res] Paul Mauriat - Après toi (1972) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/19/7apc8ramq91sp9mgfuj4lcflg.jpg)

![Black Flower - Ghost Radio (2016) [Hi-Res] Black Flower - Ghost Radio (2016) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/9jx4xnhjd3hra5u06rbmghsre.jpg)