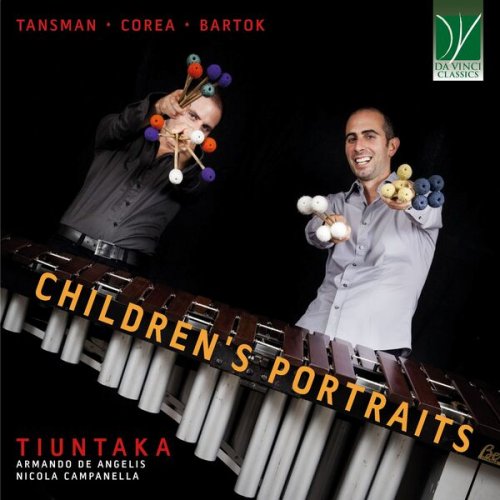

Artist:

Tiuntaka, Armando de Angelis, Nicola Campanella

Title:

Tansman, Corea, Bartok: Children's Portraits

Year Of Release:

2025

Label:

Da Vinci Classics

Genre:

Classical

Quality:

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 57:34

Total Size: 172 MB

WebSite:

Album Preview

Tracklist:01. Pour les enfants: No. 1, Le petit ours en peluche

02. Pour les enfants: No. 2, Au jardin

03. Pour les enfants: No. 3, La toupie

04. Pour les enfants: No. 4, Le petit oiseau

05. Pour les enfants: No. 5, Noel

06. Pour les enfants: No. 6, Petite reverie

07. Pour les enfants: No. 7, Le Mendiant

08. Pour les enfants: No. 8, Ping-Pong

09. Pour les enfants: No. 9, Cheval mecanique

10. Pour les enfants: No. 10, Disque

11. Pour les enfants: No. 11, Jeux Balinais

12. Pour les enfants: No. 12, Berceuse

13. Children's Songs: No. 1

14. Children's Songs: No. 2

15. Children's Songs: No. 3

16. Children's Songs: No. 4

17. Children's Songs: No. 5

18. Children's Songs: No. 6

19. Children's Songs: No. 7

20. Children's Songs: No. 10

21. Children's Songs: No. 11

22. Children's Songs: No. 12

23. Children's Songs: No. 20

24. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 1 in E Minor

25. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 2 in C Major

26. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 3 in E Major

27. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 4 in C Major

28. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 5 in A Minor

29. Mikrokosmos. Six Dances in Bulgarian Rythm, Sz. 107: No. 6 in E Minor

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child”, Pablo Picasso famously said. It is as paradoxical a statement as his art as a whole is. Yet, there is some truth in this paradox, and it is worth probing and understanding. It also can serve as the starting point for this album, which comprises works sharing their destination “for children”, but which are neither childish nor simple.

The history of human childhood is a story of a very much evolving concept. The challenges of education and parenting have been solved in very different ways according to history and culture. The Romans considered children as a property of the paterfamilias; they were not subjects in their own right, but merely “dependents”, in a fashion not dissimilar from slaves. (It is interesting that the same word, puer, could indicate both a servant and a child). Christianity brought about a substantial revolution under this viewpoint, as it did under many others. Jesus’ predilection for children, and His invitation to adults to become like children was fundamental for establishing children as “persons”, not as disposable objects. (We know that “imperfect” children were frequently simply abandoned or killed before Christianity in the Classical world; and the sacrifice of children was abolished by Christians in many cultures where the Gospel arrived, such as the pre-Colombian societies).

Nevertheless, children were still seen – in the wake of the Greek Aristotle – as “defective adults”. There rarely was an inherent worth in childhood; it was rather conceived as an immature stage to be overcome during a boy or a girl’s development. Furthermore, due to high rates of infant mortality, parents were encouraged not to bond affectively in too tight a fashion to their children, otherwise their (very likely) death in infancy would have psychologically destroyed their parents.

Also on the educational plane, there was hardly any difference on how a discipline was taught to a child or to an adult: since the child had to abandon childhood as soon as possible, the idea of instilling the notions in the same fashion as would have suited an adult was uncontroversial.

Only in the eighteenth century did educators such as Rousseau provide another perspective on childhood, albeit theirs, too, was undermined by naïve prejudices. Still, their merit lay in their focusing on the specificity of childhood, which they saw in a mythical fashion, but yet came to be regarded as a valuable and unique stage of life.

Slowly but steadily, this concept started to penetrate also the world of music teaching. The idea began to emerge that the same necessary elements (for example of musical technique) could be taught in a pleasant, rather than in a dry or arid fashion. Here too, Johann Sebastian Bach was a pioneer. His large family and numerous students provided him with a unique insight into the psychology of children. And since he wished his firstborn, Wilhelm Friedemann, to become a great musician – as he would in fact become – Bach created for him whole collections of musical works whereby musicality and technique were combined. The pieces written by Johann Sebastian for Wilhelm Friedemann educate the ear and soul besides the fingers; and they are extremely pleasurable and frankly beautiful to play and to listen to.

Whilst many of Carl Czerny’s exercises attempt to similarly unite the pleasant and the useful, they do not always succeed in doing this; but, for instance, the “easy” Piano Sonatas and Sonatinas by Beethoven and Mozart are masterpieces in their own right (although they had not been specifically designed for children, but rather for beginners, who could also be adult amateurs).

The first to write consistently and beautifully for child pianists was Robert Schumann: not by chance, another father of many children. While his Kinderszenen are not really pieces “for children”, but rather “about childhood”, his Album für die Jugend and other pieces for young players stand among the finest works ever written for young artists. The colourful and vivid imagination of the composer, his fantasy – which he abundantly demonstrated both as a musician and as an author -, his own experience with children, and his poetical perspective were all fundamental elements which helped him to establish a new genre, that of piano music for children.

Among the composers who followed him, a special mention is deserved by Russian musicians such as Čajkovskij and Mussorgskij; indeed, the Russian piano school would bring about many fascinating works of this genre. Precocity was highly regarded and encouraged in Russia as concerns the artistic field; and if it is true that Russian pedagogues were not always tender and gentle with the children entrusted to their care, many others were particularly attentive to this dimension.

Another musician to whom we owe a masterpiece for young musicians is Claude Debussy, whose Children’s Corner is, yet again, a cycle which figures regularly on the concert stage, performed mostly by adults, due to its irony, poetry, and to the noteworthy complexity of its writing, in terms of both technique and musicianship. This does not prevent it to be played also by (gifted) children, of course, “under an adult’s guidance”, as the saying goes.

The three cycles recorded here make at times explicit references to these and to other works of the past, contributing to the establishment of a tradition of “children music” which includes magnificent works.

Alexandre Tansman had been an exceptional child prodigy himself. He had started composing at a very young age, so, arguably, he had not experimented first-hand the hardships and difficulties felt by many budding musicians who are not blessed with a talent similar to his own. Yet, he evidently sympathized with them, and therefore wrote several collections of music for children, which is always spirited, delightful, and at the same time adroitly useful and brilliantly creative.

His style had been crafted under the aegis of Chopin, the greatest Polish musician; as a Polish Jew, however, Tansman had to flee his home country due to the Nazi persecution of Jews. The committee which organized his flight comprised some of the most brilliant artists of the era, including Charlie Chaplin and Artur Rubinstein. His return to Poland, after the war, was hailed with great acclaim by his fellow citizens, but Tansman suffered the pression of the Communist regime rather intensely; one of his last works is dedicated to Lech Walesa, although, sadly, Tansman passed away before seeing the triumph of Solidarność and the liberation of Poland.

The pieces excerpted from his Pour les enfants are among the most representative and original of the series, although generally speaking all pieces in these collections are a genius’ work.

Echoing the above-mentioned Children’s Corner by Debussy, Chick Corea’s album Children’s Songs is a refreshing and innovative take on children music, seen from the vantage point of a jazz musician. Whilst in the recent years there has been a great flourishing both in the field of jazz music and in that of early music, the underlying idea is that the first step for a young musician is to be trained in classical art and performance, and only later will he or she be initiated to these different fields. If one can see some positive aspects of this approach, there also are negative sides which should not be overlooked. The spontaneity with which a child will approach both early and jazz music, is precociously exposed to it, is a mark of a musician’s artistry, and therefore would need to be cultivated more seriously.

In spite of this, here too it is disputable whether this cycle would really suit a child, even a gifted one. Here, it is the “soul” of childhood which Corea tries and reproduces. In his own words, his aim was “to convey simplicity as beauty, as represented in the Spirit of a child”.

In this, Corea was walking in the wake of Béla Bartók, whose work closes this album. (Corea’s Children Songs, it should be specified, originates as a recording [1983] in which he featured alongside violinist Ida Kavafian and cellist Fred Sherry. Also to be noted is Corea’s adept reuse of materials found in some of his preceding works for these pieces).

With Bartók, Corea shares such stylistic traits as an abundant use of modality (in particular as concerns pentatonic scales), a relevant presence of non-conventional rhythms and tempos, a capability for aphoristic writing, and the organization of the pieces by degrees of complexity, leading from the easiest to the most complex pieces.

Indeed, the Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm by Bartók are found at the very end of his monumental work Mikrokosmos, and are therefore the most difficult pieces of the series. They constitute a suite within the suite, and were dedicated to English pianist Harriet Cohen. Written between 1926 and 1939, Mikrokosmos is now regarded as an absolute masterpiece of piano literature and pedagogy. In it, Bartók brought and poured his global musical experience: his knowledge and study of traditional folk music of Eastern Europe (as is clearly demonstrated precisely by the pieces recorded here); his extensive experience as a pedagogue; his brilliant pianism; and his capability to innovate the musical language with previously unheard-of gestures and traits.

Together, these works are a brilliant demonstration of Picasso’s statement quoted at the beginning: that it takes a lifetime to achieve a child’s simplicity and to retrieve the enchanted gaze on the world which is typical for children.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2025

![Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res] Reggie Watts - Reggie Sings: Your Favorite Christmas Classics, Volume 2 (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/cn1c8l2hi7zp9j05a5u7nw49g.jpg)