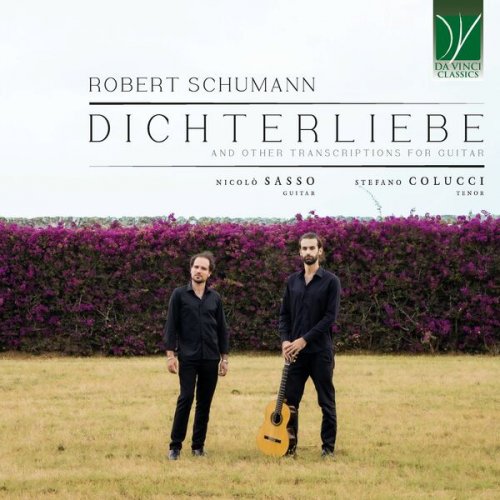

Stefano Colucci, Nicolò Sasso, Nando Di Modugno - Robert Schumann: Dichterliebe, and other Transcriptions for Guitar (2025)

Artist: Stefano Colucci, Nicolò Sasso, Nando Di Modugno

Title: Robert Schumann: Dichterliebe, and other Transcriptions for Guitar

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:50:15

Total Size: 207 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Robert Schumann: Dichterliebe, and other Transcriptions for Guitar

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:50:15

Total Size: 207 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 1, Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

02. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 2, Aus meinen Tränen sprießen

03. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 3, Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne

04. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 4, Wenn ich in deine Augen seh

05. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 5, Ich will meine Seele tauchen

06. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 6, Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome

07. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 7, Ich grolle nicht

08. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 8, Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen

09. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 9, Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen

10. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 10, Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen

11. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 11, Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen

12. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 12, Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen

13. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 13, Ich hab' im Traum geweinet

14. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 1, Allnächtlich im Traume

15. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 15, Aus alten Märchen winkt es

16. Dichterliebe, Op. 48: No. 16, Die alten, bösen Lieder

17. Nocturne, Op. 6, No. 2

18. Bunte Blätter, Op. 99: No. 1, Nicht schnell, mit Innigkeit

19. Bunte Blätter, Op. 99: No. 2, Sehr rasch

20. Bunte Blätter, Op. 99: No. 6, Ziemlich langsam

21. Carnaval, Op. 9, No. 5 Eusebius

22. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68, No. 40 Kleine Fuge

23. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 7, Träumerei

24. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 13, Der Dichter Spricht

One of the distinctive traits of Robert Schumann’s output is its tendency to coalesce by genres and by periods. For instance, the very first fruits of Schumann’s pen are entirely consecrated to the solo piano. But whereas Frédéric Chopin would largely remain a “solo piano” composer (with notable, albeit sparse, exceptions), Schumann later began to explore different fields, to the point that there are significant periods of his creative activity with no new piano works.

His oeuvre in the genre of the Lied, the song for voice and piano which is so quintessentially “German Romantic”, can likewise be observed as an extraordinary conglomeration of works written mainly in or around 1840, the Liederjahr, the “year of the Lieder”. It is perhaps more surprising to observe that Schubert waited until his thirties to dedicate himself intensely to the Lied, than to be amazed by their beauty. While this is undeniable – to the point that Schumann is rightfully counted among the greatest composers of Lieder ever – one could actually expect such a flourishing by a musician with Schumann’s qualities.

The success of a Lied depends in fact on several factors. One of them are its lyrics (although this aspect, in spite of what one could imagine, is not determining. There are stupendous Lieder by Schubert which set to music rather awkward lyrics). Still, when a Lied’s verbal text is beautiful, musical, smooth, and full of emotional content, it is doubtlessly more likely that the final result will stand the test of time. (Indeed, this is true only when the emotional and affective palette of the words is in syntony with the composer’s own mood, or at least with their capability for empathy. At times, the emotional world of composer and poet are so at odds with each other that the clash is evident even to the less expert ears).

In the case of Schumann, there was every anticipation that the syntony between composer and lyricist would be perfect. Firstly, Schumann was hand-picking those songs with which he felt particular in agreement, both emotionally and literarily. Secondly, he was turning his attention to one of the most important poets of his era: Heinrich Heine, who, by a curious turn of destiny, would die in the same year as Schumann himself. Thirdly, Heine’s style was perfectly suited to that of Schumann. Both displayed a typical dualism between humour and poetry. For Schumann, this would take the form of “Florestan” and “Eusebius”, the two fictional characters which he adopted as his pen-names, both in his literary and in his musical activity. In fact, our fourth point regards precisely Schumann’s expertise in the literary field: an expertise which was probably unmatched by any other composer, either at his time or later. Both Heine and Schumann had hesitated before finding their right path in life; indeed, both had been law students, and only later did their find their true artistic vocation. In Schumann’s case, the uncertainty lasted rather long between a career as a literary author and one as a musician; and although in the end his choice fell on music, literature never truly abandoned him. He wrote extensively, mainly on the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, a paper he had personally founded – and this already speaks volumes about his commitment to writing.

As briefly mentioned before, Schumann signed his articles with the names and/or initials of either Florestan (the expansive, communicative, boisterous, humorous, and frank character) or of Eusebius (the reflective, introspective, dreamy, and poetical character), or, at times, of both of them.

They were the direct offspring of two other fictional characters, i.e. Valt and Wult, the twin protagonists of Jean Paul Friedrich Richter’s Flegeljahre. These two poles of Schumann’s personality were therefore crucial for his own self-understanding, and for the depiction of the contradictions inherent in his music.

Dichterliebe, therefore, is a “predictable” masterpiece, since all the ingredients are there, and the chef is an expert. Indeed, the chef also took some liberties with the “recipe”, in a manner of speaking. For Dichterliebe he selected some among the sixty-five (!) poems found in Heine’s Lyrisches Intermezzo, which in turn constitutes the second part of his Buch der Lieder. But Schumann was not content merely in his hand-picking of the song texts which appealed most intensely to his feelings. Equipped with his own literary expertise, Schumann rearranged and re-structured the verbal material. He certainly felt that he had a right to a certain liberty: to the point that his music, at the end of the cycle, conveys a message rather different from that spoken by the words. But if Schumann had, until then, abundantly demonstrated his exceptional capability to ply the music to the requirements of the poetic word, now it was his own soul as an artist which claimed a right to a personal interpretation – and to an interpretation which propounded his own values and viewpoint. In spite of this, or perhaps precisely due to this, the result is magnificent and fully convincing.

The cycle’s title is also Schumann’s, and it probably derives – as has been hinted to by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, one of the greatest Lieder-singers ever – from a quote by Rückert: “The poet’s love has always encountered misfortune”. Dichterliebe, “the poet’s love”, thus forms the perfect response to another of Schumann’s great cycles, i.e. Frauenliebe und -leben, where women’s “love and life” constitute the object of poetry and of singing.

Framing all of this discourse about love (and about unrequited love) was, of course, Schumann’s own personal experience. The Liederjahr was in fact the year of his long-awaited marriage to Clara, an extraordinary pianist, his great love since already many years, and the lady whom Schumann had almost lost hope to marry, given her father’s decided opposition to the match. There are quotations from Clara’s own works in Dichterliebe, thus affirming the hidden truth that Dichterliebe is first and foremost a declaration of love for Schumann’s beloved.

Actually, however, the cycle was dedicated to the exceptional singer Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient; and this is particularly interesting given the absolute and overwhelming predilection of male singers for performing this cycle. In Schumann’s first idea, the cycle should have comprised twenty songs, which he had carefully chosen, arranged, and set to music. Unfortunately, however, the twenty-pieces long cycle did not meet with the publishers’ favour. It was only four years after its composition that Dichterliebe eventually found a publishing house and was printed. The publication, however, included only sixteen songs, which were premiered, in this form, in 1895. The musicians, on that occasion, were Leonard Borwick (the pianist, who amazed the audience by playing the full cycle by memory) and singer Harry Plunket Greene.

Within the cycle, a great variety of feelings and atmosphere is found. There are touching moments, moments of pure verbal delight which correspond to what is normally intended by “Romanticism”. There is plenty of flowers, in Dichterliebe, and, in spite of what could become trite poetry, the genius of both Heine and Schumann manages to infuse new life and light to the imagery employed. There is also provocation, particularly in Ich grolle nicht, whereby the poetry’s rebellious character is entirely matched by the outbursts of the music.

We said at the outset that Dichterliebe was conceived under the best auspices, given the syntony between author and musician. And one of the contributing factors, beside those already mentioned, was certainly Schumann’s own proficiency at the piano. He knew perfectly well – both as a pianist himself, and as the composer of countless piano works – what worked on a piano keyboard and what would not work. Just as his melodies are tailored to the shape and style of the verbal text, so is his instrumental “accompaniment” (for want of a better word) modelled after the potential of the piano.

How will, therefore, all this translate into a transcription for voice and guitar? The risk is behind the corner to suffocate expressivity and variety through this change of medium. It is the risk of “lost in translation”. Nevertheless, the musicians performing in this Da Vinci Classics album demonstrate their crystal-clear ideas so that their rendition is pleasantly refreshing.

To complete the album, some other transcriptions after Schumann’s works are offered (including one after a piece by Clara Schumann). Bunte Blätter, here presented in the transcription by Francisco Tárrega – who also signed several other transcriptions – is one of the late piano works by Schumann; the elan and sharp contradictions of his youthful works have been slightly tempered, and a vein of nostalgia suffuses the music. Eusebius, excerpted from Carnaval op. 9, showcases one of Schumann’s twin souls, the reflective one, with its garlands of seemingly inconsequential wanderings.

The two pieces from Kinderszenen are the perfect complements to what has been said and listened to until now. Träumerei, one of Schumann’s best-known pieces, describes precisely that daydreaming which is typical for Eusebius – and for the composer too. And the Poet, the protagonist of Dichterliebe, is also the voice speaking at the end of that piano cycle, dedicated by Schumann to childhood. After many delightful depictions of children’s games and states of mind, the last word is the poet’s; a word of nostalgia, of lyrical commentary, of touching wisdom, and also of questioning wonder. It is only the poet’s sight that can fully understand the contradictions of life; it is only the poet who can transform the odd turns of love and humour into a consistent and somewhat coherent whole: by accepting those contradictions, they become part of a global tension which gives life to music, to art, to existence itself.

![Tom Cohen - Embraceable Brazil (2025) [Hi-Res] Tom Cohen - Embraceable Brazil (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/18/vgt0kbsml69jbixcu67jkruae.jpg)