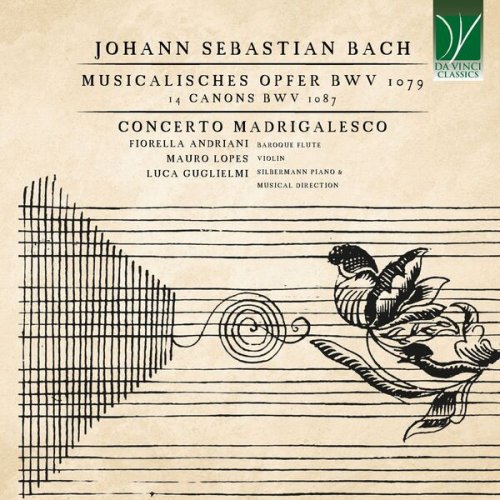

Fiorella Andriani, Mauro Lopes, Luca Guglielmi - Johann sebastian Bach: musicalisches Opfer BWV 1079, 14 canons BWV 1087 (2025) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Fiorella Andriani, Mauro Lopes, Luca Guglielmi

Title: Johann sebastian Bach: musicalisches Opfer BWV 1079, 14 canons BWV 1087

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 44.1kHz

Total Time: 01:13:01

Total Size: 338 / 684 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Johann sebastian Bach: musicalisches Opfer BWV 1079, 14 canons BWV 1087

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 44.1kHz

Total Time: 01:13:01

Total Size: 338 / 684 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Fantaisie sur un Rondeau in C Minor, BWV 918

02. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 1, Dedication (Kerstin Schwarz, narrator) Musicalisches Opfer Sr. Königlichen Majestät in Preußen

03. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 2, Thema Regium

04. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 3, Ricercar

05. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 4, Canon perpetuus super Thema Regium

06. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 5, Sonata sopr'il Soggetto Reale à Traversa, Largo 3/4

07. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079, BWV 1079: No. 6, Sonata sopr'il Soggetto Reale à Traversa, Allegro 2/4

08. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 7, Sonata sopr'il Soggetto Reale à Traversa, Andante

09. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 8, Sonata sopr'il Soggetto Reale à Traversa, Allegro 6/8

10. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 9, Sonata sopr'il Soggetto Reale à Traversa, Canon perpetuus

11. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 10, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - canon 1 a 2

12. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 11, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - 2. a 2 Violin: in Unisono.

13. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 12, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - 3 a 2 per Motum contrarium

14. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 13, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - 4 a 2. per Augmentationem, contrario motu Notulis crescentibus crescat Fortuna Regis

15. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 14, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - 5. a 2. Ascendenteque Modulatione ascendat Gloria Regis

16. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 15, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - Fuga canonica

17. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 16, Thematis Regii Elaborationes Canonicae Canones diversi super Thema Regium - Ricercar.

18. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 17, Quaerendo invenietis - Canon à 2

19. Musicalisches Opfer, BWV 1079: No. 18, Quaerendo invenietis - Canon á 4

20. Goldberg-Variationen, BWV 988/1: No. 1, Aria

21. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental=Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 1, Canon simplex

22. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 2, al roverscio

23. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 3, Beede vorigen Canones zugleich, motu recto e contrario

24. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 4, motu contrario e recto

25. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 5, Canon duplex à 4

26. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 6, Canon simplex über besagtes Fundament à 3

27. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 7, Idem à 3

28. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 8, Canon simplex à 3, il soggetto in Alto

29. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 9, Canon in unisono post semifusam à 3

30. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 10, Alio modo, per syncopationes et per ligaturas à 2

31. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 10b, Evolutio

32. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental=Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 11, Canon duplex übers Fundament à 5

33. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 12, Canon duplex übers besagte Fundamental-Noten à 5

34. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 13, Canon triplex à 6

35. Verschiedene Canones über die ersten acht Fundamental Noten vorheriger Arie, BWV 1087: No. 14, Canon à 4 per Augmentationem et Diminutionem

36. Flute Sonata, BWV 1035: III. Siciliano (Für den Kämmerier Fredersdorf aufgesetzt)

In May 1747 Johann Sebastian Bach traveled to Potsdam to visit Frederick II of Prussia, whose son Carl Philipp Emanuel served as the Court’s first cembalo and his pupil Christoph Nichelmann as the second. This visit is well-documented, with a famous encounter between Frederick, a musically trained monarch, and Bach. Frederick invited Bach to test Gottfried Silbermann’s new fortepianos and demonstrate his organ-playing skills on various church organs. During this meeting, Frederick presented Bach with a musical challenge: he provided a theme in C minor and asked Bach to improvise a three-voice fugue based on it. Remarkably, Johann Sebastian did this on the spot, without any prior preparation. What follows is also fairly well known, but from this point onwards the interpretation of events becomes crucial. Bach published an opus entitled Musicalisches Opfer, consisting of sixteen successive pieces in three fascicles, these pieces belong to three different musical forms; a Triosonata (the most beautiful and difficult ever composed), two Fugues (called Ricercari) and ten Canons. All these develop the Thema Regium, i.e. the melody Frederick had played to Bach “on the clavier”.

This composition is known as the Musical Offering. While many are familiar with this composition, not everyone is aware of its esoteric significance, leading to various interpretations and rearrangements of its pieces using different instruments and sequences. It is clear that the Musicalisches Opfer is closely related to another enigmatic work by Bach, Die Kunst der Fuga, based on counterpoint. Some years ago, the cellist and scholar Hans-Eberhard Dentler – a pupil of Pierre Fournier, and an associate of Ernst Jünger (out of humanitas), with a thorough knowledge of Latin and Greek as a classical philologist, and even mathematician – published already a study on “The Art of Fugue”, followed by a no less important study (published in Italian under the auspices of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia) on the Musicalisches Opfer, entitled Il Sacrificio musicale di Johann Sebastian Bach, which revealed its Pythagorean meaning. The interpretation commences with a consideration of the work’s title, as it was dedicated by Bach to King Frederick. Specifically, the term Opfer translates to Sacrificium, and this choice of word underscores the unique nature of this work, which can be viewed as a kind of Gradus ad Parnassum, signifying an evolutionary path toward perfection.

The second enigma comes from the Latin subtitle of the first fascicle: the initial of the words which compose it create an acrostic which produces the word RICERCAR, which echoes a contrapuntistic work typical of the Renaissance and Baroque era, the Ricercare: an instrumental form of the Motet. It is entitled Regis Iussu Cantio Et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta, which translates a “By order of the King: performance of the melody (Cantio) and of the rest (Et Reliqua) according to the Canonical Art (Canonica Arte Resoluta)”. But Canonical Art means, as Johann Gottfried Walther’s contemporary Musicalische Lexikon explains, «Canonica (lat.) kanoniké (gr.) refers to the kind of music which considers sounds not according to hearing but as a reflection on numbers. […] Those who follow this practice are called Canonical, the term which indicated and still indicate the Pythagoreans». Through consideration of the sounds not «according to hearing» one understands that Music is the echo of the Harmony produced by the rotation of the planets. Dentler’s excursus comes through Plato’s Timaeus, Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis (a key work for understanding the doctrine of the Harmony of Spheres, generated by planets, revived and paraphrased in Dante’s Commedia), the neoplatonist Giamblico, Boetius and others, coming to a milestone of modern civilization, Johannes Kepler’s Harmonices Mundi. Libri V (1619). It is important to note that Frederick ordered Nichelmann to write an Oratorio on Scipio’s Dream, which the composer realised with Metastasio’s Italian text. The Musical Sacrifice is therefore intended as the realization of an item which Kepler asked the composers to produce. The composition, which would present the representation of the Harmony of the Spheres and of the Quadrivium (Boetius’ subdivision of the Liberal Arts) was never performed before or after Bach.

Frederick II “the Great”, King of Prussia, was a Freemason and he liked to sign his correspondence Philosophe de Sans-Souci and defined as “Copernican Prince”, as his friend and correspondent Voltaire said. The esoteric masterpiece was written for him (since he had ordered it) to understand. The succession of the movements can only be the one presented in the original edition, which scholars in the past (and until today) have misunderstood.

At the end of the day, we can therefore say that the Musicalisches Opfer is a composition which has always been misinterpreted by critics, who have always seen it as a form of court homage. In fact, below the superficial veil of the humble “act of gratitude” (as a contemporary source labelled it) Bach was creating a monument to the most important concept for a musician and for a True Christian, namely that music was nothing more than an earthly and material reflection of the much higher and spiritual “Music of the Spheres”.

Through the public homage to Frederick II of Hohenzollern, Bach left to Posterity and to the World his own Credo as a “musico prattico”, who could blend the highest artistic learning with the devotion appropriate for a Knowing Christian.

Bach’s meeting with his former pupil Lorenz Mizler enabled him, in June 1747 (a month after the famous trip to Potsdam and the related evening at the Stadtschloss) to become the fourteenth member (sic! BACH=14, 2+1+3+8, where a=1, b=2, c=3, etc.) of the Correspondierende Societät der musicalischen Wissenschaften [Corresponding Society for Musical Sciences, 1738-1761], of which Mizler was the first founding member, under the name of “Pythagoras”.

In this numerological context, the selection of the date for the dedication of the Musical Sacrifice assumes a significance that goes beyond mere coincidence. Indeed, on the 7th of July 1747 (7-7-1747), the number fourteen appears three times, echoing the repeated occurrences of the word Thema, which are also emphasized through italics. The sum of 7 and 7 equals 14 twice, while the individual digits, 1 and 4, together form the number 14. Also the subtitle of the last section, Quaerendo invenietis, brings Bach’s name in it, being from the Gospel of Matthew, seventh versicle of the seventh chapter. Again 7 + 7 = 14.

From all this it is possible to deduce the secret, esoteric and religiously inter-confessional nature which defined Mizler’s society, its work, and its members. From this derives also the attempt to “explain” (inasmuch one may justify a free artistic creative act) the completion of the Mass in B minor (BWV 232) in the years in which Bach joined it. While the decision to address the Missa tota form appears to be in line with Bach’s attitude of his later years, the “universal” nature of this choral masterwork seems almost his supreme moral effort to stretch beyond himself as a Musicus as well as an earthly Man.

![Double Drums, Philipp Jungk & Alexander Glöggler - All You Can Beat (2026) [Hi-Res] Double Drums, Philipp Jungk & Alexander Glöggler - All You Can Beat (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771946421_folder.jpg)

![VA - 20 Years Into An Infinite Musical Journey (2025) [SACD] VA - 20 Years Into An Infinite Musical Journey (2025) [SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771834929_ff.jpg)