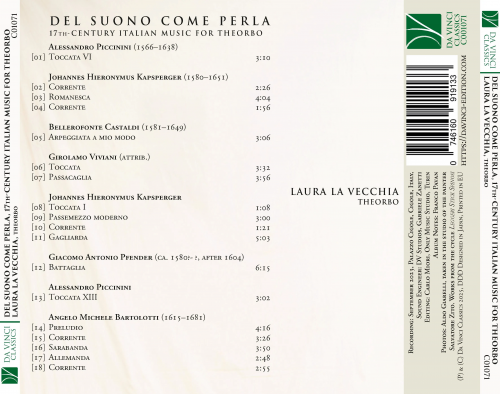

Laura La Vecchia - Del suono come perla: 17TH-century italian music for theorbo (2025)

Artist: Laura La Vecchia

Title: Del suono come perla: 17TH-century italian music for theorbo

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Theorbo

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:59:14

Total Size: 263 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Del suono come perla: 17TH-century italian music for theorbo

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Theorbo

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:59:14

Total Size: 263 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Intavolatura di liuto, et di chitarrone, Libro Primo: Toccata VI

02. Manuscript of the Albani Archive, Pesaro, No.1: Corrente

03. Manuscript of the Albani Archive, Pesaro: Romanesca

04. Manuscript of the Albani Archive, Pesaro, No.2: Corrente

05. Capricci a due strumenti, cioè Tiorba e Tiorbino: Arpeggiata a mio modo

06. Manuscript Modena, Archivio di Stato: Toccata

07. Manuscript Modena, Archivio di Stato: Passacaglia

08. Manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque Musicale, ms. Mus. Res. Vmd 30: Toccata I

09. Manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque Musicale, ms. Mus. Res. Vmd 30: Passemezzo moderno

10. Manuscript of the Albani Archive, Pesaro, No.3: Corrente

11. Libro terzo di intavolature per chitarrone: Gagliarda

12. Manuscript Modena, Archivio di Stato: Battaglia

13. Intavolatura di liuto, et di chitarrone, Libro Primo: Toccata XIII

14. Manuscript Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 17706: Preludio

15. Manuscript Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 17706 No.1: Corrente

16. Manuscript Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 17706: Sarabanda

17. Manuscript Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 17706: Allemanda

18. Manuscript Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 17706 No.2: Corrente

Silence: that silence which swiftly and infinitely connected the performer to the absolute, to a sense of sacredness in the musical act that today is all but forgotten. A silence not merely imposed by the Harpocratic gesture, but deeply felt within, suspending the onset of sound. In that moment, the millennia-long history of humankind would condense—the tension between the unknown and the material, the painful joy of knowing that the act about to unfold would be fleeting, yet necessary. This is but a small, albeit immense, example of what we have lost—something that once was life, necessity, and hope.

Today, we are drowning in music histories that demand narratives about composers and works, with clear beginnings and, ideally, some sort of development. Stories that must necessarily seek out “genius” composers whose “voice” marked our cultural heritage. But none of this shaped our path—at least not until well into the nineteenth century. Those earlier composers shared a mother tongue: counterpoint. And with that language, they conversed, they grew together. The singer, if fluent in that language, became a bridge-builder, extending a hand to colleagues and sketching sonic architectures. And the instrumentalist followed the same path.

Such was the fate of theorbo players—or rather, chitarrone players. The first documented references to this peculiar instrument date back to the 1580s, at the Medici court in Florence. It was originally what they called a “large lute,” fitted with a special tuning in which the third course, like all others doubled, was the highest. Later, likely between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a second pegbox (the tratta) was added to accommodate a series of lower-pitched strings, eventually bringing the instrument to its maximum of 19 courses.

At the turn of the century, musicians began to recognize the chitarrone’s potential as a solo instrument. Its unique range—focused on the bass—and the addition of extra-low strings (inspired by the archlute, invented by Alessandro Piccinini) gave the chitarrone a distinctive timbral identity. This was first fully realized by a young Venetian of German descent, Johannes Hieronymus Kapsperger (1580–1651—though even his birthdate remains uncertain). Already as a youth, alongside his “most beloved brother” Giacomo Antonio Pfender, even younger than he, Kapsperger became one of the instrument’s foremost exponents.

He published his first book for the chitarrone in 1604, showcasing his total mastery of the instrument. He would go on to write five more books for it, though only three survive today. His language is bold and iconoclastic, overturning the established rules of lute music with his daring metric design, obsessive timbral explorations, extreme virtuosity, and dramatic formal contrasts. Following in his footsteps, many musicians embraced the chitarrone, gifting us with magnificent works.

Kapsperger’s travels—from Venice to Augsburg, back to Venice, then Naples, and finally Rome under the patronage of Urban VIII and the Barberini family—helped spread this newly discovered solo instrument. Anne-Marie Dragosits’s research is shedding light on many still-obscure aspects of Kapsperger’s life: his peculiar childhood with his obsessive mother Dorothea Hummel, likely responsible for her husband’s death when Johannes was still an infant; his early years in Rome at the White Lion inn run by his mother and stepfather Hieronymus Pfender; his education in Germany and Naples; and his eventual return to Rome.

Kapsperger became a pivotal figure in the new music—the seconda pratica—also in the vocal sphere, publishing madrigals, arias, villanelle, and sacred motets. Despite his abrasive temperament and occasional arrogance, he became a towering figure in the world of lute and chitarrone music. The few surviving works by his brother Giacomo Antonio Pfender—Dorothea’s son from her second marriage—reveal a style closely related to Kapsperger’s, as shown in the striking Battaglia, likely the very piece cited by Johannes Hieronymus in his own Battaglia from the Libro Quarto d’Intavolatura di Chitarrone (Rome, 1640).

A different story is that of Alessandro Piccinini (1566–before April 15, 1639). Born into a family of virtuoso lutenists in Bologna, he became a foundational figure in the history of both the lute and the chitarrone. Together with his father Leonardo Maria and brothers Giacomo and Filippo, he moved to the Este court in Ferrara. Following the 1597 devolution of the duchy to the Papal States, they settled in Rome, and eventually split: Giacomo died in the Low Countries; Filippo went to Spain, only returning years later to die in 1648. Alessandro returned to Bologna and maintained close ties with the powerful Bentivoglio family for many years.

In 1623, Piccinini published his groundbreaking Intavolatura di liuto, et di chitarrone, Libro Primo with the heirs of Giovanni Paolo Moscatelli. This volume demonstrates his supreme instrumental artistry—firmly rooted in the extraordinary Ferrarese tradition, yet attentive to new trends. His command of counterpoint, that mother tongue, is at its peak here, accompanied by a rich set of rules and observations for playing the lute and chitarrone—unmatched in the Italian tradition. By “lute,” Piccinini meant the archlute—the very instrument he invented in collaboration with the luthier Heberle in Padua, which would shape European music for the next two centuries. This invention inspired, as mentioned, the addition of the tratta to the chitarrone.

Initially reluctant to compose for the new instrument—as we know from his letters—Piccinini began by adapting archlute works for the chitarrone. But by 1623, the pieces in his volume reveal his full command of the instrument’s idiom: far from Kapsperger’s eccentricities, his style follows the lofty path of Luzzasco Luzzaschi, while remaining strikingly original. Piccinini’s son, Leonardo Maria, would publish a second book of intabulations in 1639, dedicated to Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio. While some works likely bear Alessandro’s hand, others are probably by his son, and still others are drawn—undisclosed—from foreign sources like Antoine Francisque’s repertoire. The Piccininis’ musical legacy would end with Leonardo Maria, closing a centuries-long lineage.

A more eclectic and anarchic figure was Bellerofonte Castaldi (1580–1649), a brilliant Modenese polymath and extraordinary theorbo player. He preferred the name tiorba—a term that would definitively replace chitarrone from the 1630s onward. Admirer and acquaintance of Claudio Monteverdi, friend of poets like Fulvio Testi, restless dweller of Modena and frequent traveler (Naples, Venice), often at odds with the law, Castaldi was also a poet—sharp-tongued and unapologetically scornful toward the people and social environments he despised.

In 1622, he published a seminal volume for the theorbo, Capricci a due strumenti, cioè Tiorba e Tiorbino, engraved entirely by his own hand on copper plates in various printings. The tiorbino, an octave higher variant of the theorbo, was his own invention. Castaldi’s music is dedicated to the pursuit of refined timbral beauty, demanding an extreme kind of virtuosity—not the superficial virtuosity of speed, but one that delves into the soul of the instrument, bringing it to light and making it known.

Also from the Emilia region was Angelo Michele Bartolotti (early 17th century–after 1699), a highly gifted guitarist and theorbo player who travelled extensively between Italy and France. His few surviving pieces for theorbo are exquisitely crafted, blending Italian and French idioms, and accompanied by an important method for the instrument published in Paris in 1669.

Not far stylistically from Bartolotti is the anonymous author of a manuscript preserved in the Modena State Archives—traditionally attributed to Girolamo Viviani, though he was likely only its owner. The extraordinary passacaglia it contains, with its long sequence of remarkable variations, leads us back to silence—that resounding silence we so desperately need today.

![Chewing, Dave Harrington, Ryan Hahn, Spencer Zahn - Quintet (Live in Los Angeles) (2025) [Hi-Res] Chewing, Dave Harrington, Ryan Hahn, Spencer Zahn - Quintet (Live in Los Angeles) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/12/owakjkfg0whflv2rzyocno89p.jpg)

![Yasuhiro Usui, Ryoko Ono and Taro Tatsumaki - The House Concert Live Collection, Vol. 55: Yasuhiro Usui (Live at 3rd Floor, Artist House, Daehak-ro, Seoul, 7/12/2015) (2025) [Hi-Res] Yasuhiro Usui, Ryoko Ono and Taro Tatsumaki - The House Concert Live Collection, Vol. 55: Yasuhiro Usui (Live at 3rd Floor, Artist House, Daehak-ro, Seoul, 7/12/2015) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765791289_rchn1y2nh7yfb_600.jpg)