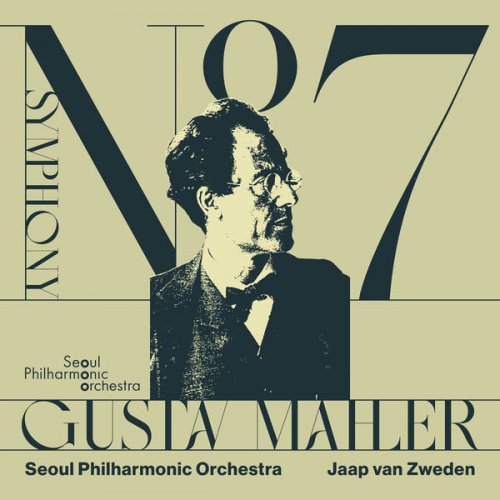

Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, Jaap van Zweden - Mahler: Symphony No. 7 (2025) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, Jaap van Zweden

Title: Mahler: Symphony No. 7

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Platoon

Genre: Classical

Quality: falc lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:14:21

Total Size: 348 mb / 1.3 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Mahler: Symphony No. 7

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Platoon

Genre: Classical

Quality: falc lossless (tracks) / flac 24bits - 96.0kHz

Total Time: 01:14:21

Total Size: 348 mb / 1.3 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Symphony No. 7, GMW 47: I. Langsam – Allegro risoluto, ma non troppo

02. Symphony No. 7, GMW 47: II. Nachtmusik I. Allegro moderato

03. Symphony No.7, GMW 47: III. Scherzo. Schattenhaft

04. Symphony No. 7, GMW 47: IV. Nachtmusik II. Andante amoroso

05. Symphony No. 7, GMW 47: V. Rondo-Finale. Allegro ordinario

In many ways, the Seventh is the least understood of all Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. Unlike many of his other compositions – in which he lays bare his soul with detailed programmes, subtitles and often sung texts – here only the titles of the second and fourth movements – ‘Nachtmusik’ – are offered up as a clue. (The subtitle ‘Lied der Nacht’, which is sometimes attributed to the symphony, was only later coined by a publisher, much to Mahler’s disapproval.) The music is otherwise abstract and at times rather unruly, thus inviting a deeper and more effortful exploration of its elusive meanings.

In the summer of 1904, the same period in which he composed his pessimistic Sixth Symphony (with its legendary fateful hammer blows), Mahler also wrote the two ‘Nachtmusik’ movements of the Seventh. Occupied with the demands of a flourishing career as a conductor, Mahler generally did not have time to compose during the rest of the year. It was only in the following summer that he would compose the other three movements. However, the symphony would not be premiered for several more years. In the interim, personal tragedies and challenges – his eldest daughter’s death, his departure from the Vienna Hofoper and the diagnosis of his incurable heart condition – marked this period, during which Mahler continued to revise the work. It is quite possible that the ambiguous atmosphere that permeates the symphony emerged from these later revisions.

In contrast with the ‘classical’ four-movement structure, the Seventh Symphony is symmetrically arranged in five movements. The outer movements are by far the longest, serving as bookends which are polar opposites of each other (like night and day) – while the two ‘Nachtmusik’ movements, for their part, flank the grim Scherzo at the centre of the work. The heart of the symphony, and perhaps its greatest enigma, is the shortest movement of all. Rather than functioning as an emotional core, it is largely characterised by bleak sarcasm. Throughout the work, Mahler interweaves parodies of other music – from nods to Joseph Haydn and Richard Wagner to Austrian folk dances and Jewish klezmer – some theorising that the idiosyncratic structure of the work actually constitutes Mahler’s own parody of himself.

Indeed, the score brims with quintessentially Mahlerian traits, including ‘progressive tonality’, a term used to describe a work that begins and ends in different keys. The harmony, of course, is often very unstable and presages the atonality that Arnold Schoenberg would soon embrace. In addition, the work is scored for a vast number of players and features unusual instruments like the tenor horn, guitar, mandolin and cowbells. Despite this, many passages bear more resemblance to chamber music, with only a few soloists.

From the very first notes in the tenor horn, the first movement unfolds as an erratic, dismal affair. The accompaniment pulsates relentlessly, the harmony never settling; with so much of the melodic material carried by the brass, the overall effect is one of marching music gone awry. Although the strings eventually assume the lead for a more pleasant interlude, their prominence is short-lived. Halfway through the movement, the music abruptly grows quiet. The trumpets continue to dominate, yet are now accompanied by solo strings and later the harp. Here Mahler invokes a palette suggestive of the lush cinematography of Hollywood films many decades later. Finally, the tenor horn reasserts itself with its sinister march, the rest of the movement characterised by perpetual restlessness and a sense of panic.

The first ‘Nachtmusik’ opens with a call and response between two horns, one of which is muted. This duet heralds each new section, which Mahler likened to an ‘night-time walk’ on which a variety of characters make their appearance. Sombre march music returns alongside imitations of bird calls, cowbells and even hints of what could have been a Viennese waltz, all suffused with the melancholy of the horns.

At the heart of the Seventh lies a Scherzo, yet one that is far from playful. Theoretically a ländler in three-quarter time, an element found in nearly all Mahler’s works, it defies the genial, pastoral character we expect, resembling something more akin to a nightmare, with skittish melodies and sudden dynamic transitions. In addition, the instrumentation is startlingly sinister and features sparse, isolated thunderclaps from the timpani, horns and clarinets in an extremely low register, and numerous glissandi and solos for viola and double bass. The central Trio attempts to offer a brief respite from the macabre, but in vain, leaving behind only fragmented echoes as the Scherzo goes out like the snuff of a candle.

In contrast, the second ‘Nachtmusik’ is far more delicate and graceful than all the material that has come before it. If not a literal serenade, it certainly evokes the stereotypical image of a lover singing beneath the balcony of his beloved. Alongside two harps, the guitar and mandolin further enhance the effect. Although this is instrumental music, each melody is imbued with a sentimental cantabile quality. Moreover, Mahler employs very small ensembles – a few woodwinds, a horn, a solo violin and muted strings – to avoid overwhelming these instruments. Of course, beneath all the romance is a subtly sarcastic undertone, and the harmony is occasionally unsettled. In addition, the music falls silent twice in the middle before evoking eerie church bells (this is night music, after all).

Bursting with energy and bravura, the finale opens with timpani and trumpets – like an unexpected early morning reveille after the night’s escapades. Moments later, lively counterpoint emerges from the orchestra, setting the tone for the rest of this final movement. Much like the opening movement, the music is often chaotic and restless, yet here it is imbued with distinctly major-key colouring. There is waltzing and marching, the music threading its way along paths and avenues, accompanied by the pealing of bells and the blaring of horns. The manic energy of this finale even prompted questions from critics, to which Mahler enigmatically replied, ‘The world is mine!’

![Ex Novo Ensemble - Claudio Ambrosini: Chamber Music (2020) [Hi-Res] Ex Novo Ensemble - Claudio Ambrosini: Chamber Music (2020) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/22/z541qb9ul4q390uxlw1d9iak3.jpg)