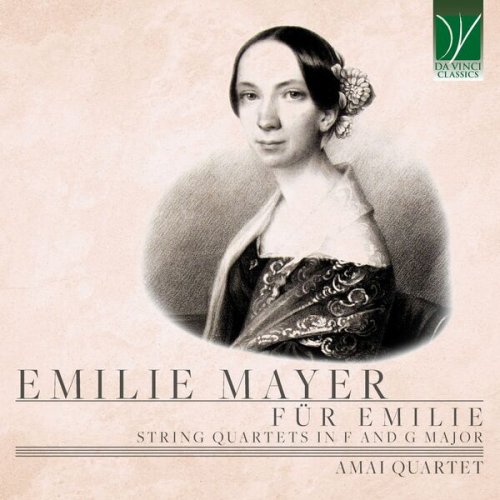

Amai Quartet - Emilie Mayer: String Quartets in F and G Major (2025)

Artist: Amai Quartet

Title: Emilie Mayer: String Quartets in F and G Major

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:53:50

Total Size: 266 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Emilie Mayer: String Quartets in F and G Major

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:53:50

Total Size: 266 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. String Quartet in F Major: I. Allegro Moderato

02. String Quartet in F Major: II. Scherzo. Allegro

03. String Quartet in F Major: III. Andante cantabile

04. String Quartet in F Major: IV. Allegretto. Finale

05. String Quartet in G Major: I. Allegro moderato

06. String Quartet in G Major: II. Adagio

07. String Quartet in G Major: III. Scherzo. Allegro assai - Trio. Più lento

08. String Quartet in G Major: IV. Allegro vivace. Finale

Emilie Mayer (1812–1883) was one of the most prolific female composers of the nineteenth century and a central figure in German instrumental music of her time. She wrote with extraordinary confidence and originality, especially in the chamber-music repertoire, which became the privileged field for the refinement of her style and the consolidation of her artistic identity. To appreciate her achievement, it is necessary to consider the wider cultural and professional networks that shaped nineteenth-century musical life. The presence and visibility of women composers varied considerably across regions, with Germany and France appearing to offer comparatively more fertile ground, yet the overall picture remains complex and continues to invite further research. Within this multifaceted context, Mayer stands out as one of the most compelling examples of discipline, talent, and determination applied to the art of composition.

Not much is known about her life, yet the sparse testimonies of her contemporaries, together with the few surviving biographical notes, paint the image of a woman with an independent and somewhat eccentric personality, determined to live by her music without making compromises. In 1850, when she moved to Berlin, she had a plaque fixed next to her doorbell reading “Emilie Mayer, Composer,” and a few years later, in 1862, the writer Marie Schilling, a friend of her niece, described her as follows:

“She did not care about appearing presentable; she was easygoing, not necessarily following conventions; she was forgetful, and for that reason she would pin essential objects to her clothes, whether an umbrella or her glasses. E.M. would sometimes attend festive ceremonies without even a hat – unthinkable for a lady – and she amused herself with the astonishment of those present.”

Emilie Mayer was the daughter of a pharmacist in the town of Friedland, in the region of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern northeast of Berlin. She received her first piano lessons at the age of five from the town organist and, after her father’s death, she continued her studies in nearby Stettin, becoming a pupil of the famous composer Carl Loewe. She never married, a choice that, while less common within bourgeois society, allowed her to devote herself entirely to her artistic career. She spent her life mostly between Berlin—where she also studied with the music theorist Adolph Bernhard Marx—and Stettin, engaging with various musical genres. She began with sonatas and youthful chamber works, then, during her Berlin period, composed symphonies and numerous orchestral pieces, refining her mastery of chamber-music writing, which culminated in her twelve string quartets, eight of which survive today. Later she turned to piano music and lieder.

In the years between 1870 and her death, Emilie Mayer gradually reduced her compositional activity. While still based in Berlin and maintaining some ties to the city’s musical life, she focused mainly on revising her earlier works, seeking to secure their publication and circulation. No new major compositions are known from this period: her creativity turned instead to shorter vocal or piano pieces, though without the intensity of her earlier years.

Despite her recognized talent, she never received official appointments, and her final years were marked by a certain isolation. She died in 1883 in Berlin, and, having no direct heirs, she was forgotten by much of the public.

Mayer’s career, far from being an isolated phenomenon, reflects a broader pattern in which many nineteenth-century women composers built professional reputations independently, without relying on familial or marital associations. The more familiar cases of Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn, Clara Schumann, or Alma Mahler-Werfel—whose biographies became closely linked to those of famous male relatives—were in fact exceptions within this wider landscape. By contrast, numerous contemporaries in the German-speaking world, among them Luise Adolpha Le Beau, Josephine Lang, Sophie Menter, and Agnes Zimmermann, pursued their artistic paths autonomously. Today she is being rediscovered as part of a wider constellation of nineteenth-century women composers whose work is attracting renewed attention. Alongside her German contemporaries—such as the above mentioned Fanny and Clara—and figures from other traditions, including the French composer Louise Farrenc, Mayer represents one of the many significant voices that contributed to shaping the musical culture of her time...

![Rick Braun - Intimate Secrets (1992) [CDRip] Rick Braun - Intimate Secrets (1992) [CDRip]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772427179_5.jpg)