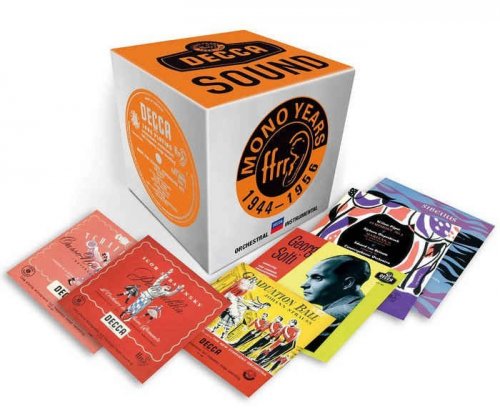

VA - Decca Sound - Mono Years 1944-1956 [53CD Limited Edition Box Set] (2015)

Artist: Various Artists

Title: Decca Sound - Mono Years 1944-1956

Year Of Release: 2015

Label: Decca [478 7946]

Genre: Classical, Baroque, Romantic, Contemporary

Quality: 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks+cue, log)

Total Time: 53 CD

Total Size: 8.55 gb / 10.40 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: Decca Sound - Mono Years 1944-1956

Year Of Release: 2015

Label: Decca [478 7946]

Genre: Classical, Baroque, Romantic, Contemporary

Quality: 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks+cue, log)

Total Time: 53 CD

Total Size: 8.55 gb / 10.40 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

The classical record industry remains in a funk, if not outright free fall, yet now is actually a great time to be collecting older classical recordings. Perhaps it’s desperate measures for desperate times, but the companies we still consider the major labels—Universal (formerly PolyGram), Sony (formerly Columbia) and Warner (formerly EMI)—have been mining their archives as never before and issuing an abundance of massive boxed sets at relatively cheap prices. In some cases, music lovers must depend on the foreign arms of Amazon and other overseas retailers for these collections, though a good many of them are readily available domestically.

Care to hear the singular pianist Vladimir Horowitz’s Carnegie Hall performances from 1943 to 1978? Sony has a box of 41 CDs for you. Perhaps that paragon of fiddling Jascha Heifetz is more your speed. No problem: Sony and RCA have partnered on a box (more like a shelf) of 104 discs containing almost everything he ever recorded. Too much? Then take a baby step with a gem from Warner Classics: an eight-CD set featuring the underrated mid-20th-century Polish pianist Witold Małcużyński, part of the larger Icon series inherited from EMI.

Among the most notable recent additions in this deluge is an especially choice box from Decca (a label founded in 1929 and now part of Universal). Titled “Decca Sound: The Mono Years, 1944-1956,” the set follows two others devoted to Decca’s sonic and artistic legacy. But the excitement generated by this one rests squarely on its artistic value. Not that there’s anything wrong with the sound. Though the great leap forward in recording technology would come in the mid-1950s with the widespread adoption of stereo sound, late-mono Deccas were renowned for their relative realism, thanks to the company’s success in capturing increased frequency range (a byproduct of its efforts to help identify German submarines during World War II) and the arrival of long-playing vinyl records beginning in the late 1940s.

Though Decca has always been a proudly English company—hence its catalog’s outsize devotion to composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Walton and Britten—it has never allowed parochialism to cloud artistic judgment. Which is why the label proved so hospitable to an internationally celebrated roster of mid-20th-century performers. The conductors alone compose a map of Europe, with Ernest Ansermet (Swiss), Ataúlfo Argenta (Spanish), Adrian Boult (English), Eduard van Beinum (Dutch), Roger Désormière (French), Erich Kleiber (Austrian) and Georg Solti (Hungarian) merely the most notable. And all are represented (some more than once) by music long associated with them.

Special mention should be made of Ansermet’s vivid 1949 account of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” with the Geneva-based Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. It was Decca’s first LP and is fittingly this set’s first disc, coupled with Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” recorded by the same forces the following year. Ansermet and the orchestra, which he founded in 1918, became mainstays of the label until his death in 1969, but they were at their peak in the late-mono period.

The list of instrumental soloists is no less impressive, nor less international. The great German pianist Wilhelm Backhaus—who surveyed Beethoven’s 32 sonatas not once but twice for the label—appears in Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto and Brahms’s two cello sonatas (with Pierre Fournier). And the sublime English pianist Clifford Curzon, who set benchmarks for elegance and eloquence, offers those virtues in his 1953 recording of Brahms’s First Concerto. Connoisseurs of the violin can debate the merits of an idiosyncratic account of the Beethoven Concerto by the aged Mischa Elman, or pick from several works played by the ill-starred French fiddler Christian Ferras, whose Brahms Concerto may be a disappointment, but whose performance of Joaquin Rodrigo’s little-known “Concierto de Estio” proves as sunny as the summer it’s meant to evoke. And two discs headlined by the Italian-born, English violinist Alfredo Campoli should be required listening. His cogent and heartfelt 1954 performance of Elgar’s Concerto remains unsurpassed, and no assortment of Fritz Kreisler bonbons, including the composer’s own, evinces sweeter tone or greater charm than the one here.

Surprises abound in this collection—whether in terms of overlooked corners of the repertory or now largely forgotten but still worthy artists—but the most gratifying concern chamber music, an essential aspect of classical music too often neglected by large record companies. This collection pays proper tribute to the great British practitioners of the form by offering the Griller Quartet’s rigorous readings of four of Ernest Bloch’s five string quartets, as well as fleet performances of Mozart’s two piano quartets with Curzon and members of the Amadeus Quartet. But an even greater claim for the label’s sophistication comes from its engagement of Continental ensembles.

Those enamored of Danish music and musicians need look no further than the Koppel Quartet (named for a violist!) performing works by Carl Nielsen and Vagn Holmboe. And fans of the melodiously named Trio di Trieste will be delighted to find its relaxed performances of piano trios by Beethoven and Brahms. Even one of the world’s rare permanent piano quintets—known both as Quintetto Chigiano and the Chigi Quintet—gets star treatment, performing works by Boccherini, Brahms and Shostakovich. And for a taste Mitteleuropa, there’s the Végh Quartet in music by Schubert, Bedřich Smetana and Zoltán Kodály, and the Vienna Octet reveling in Mozart, Mendelssohn and Brahms.

One could say this box offers an embarrassment of riches. But why be embarrassed? Decca deserves only praise for fulfilling the long-held wishes of its core customers—and in such grand fashion, too. And collectors needn’t feel abashed at finally getting at least some of what they’ve long awaited. If there’s a quibble, it’s only to point out the absence of vocal music from this set—something Decca hints it will soon remedy. Until then, we can listen repeatedly to the treasures now in hand while insisting, in the best English tradition, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

Mr. Mermelstein writes for the Journal on classical music and film.

Care to hear the singular pianist Vladimir Horowitz’s Carnegie Hall performances from 1943 to 1978? Sony has a box of 41 CDs for you. Perhaps that paragon of fiddling Jascha Heifetz is more your speed. No problem: Sony and RCA have partnered on a box (more like a shelf) of 104 discs containing almost everything he ever recorded. Too much? Then take a baby step with a gem from Warner Classics: an eight-CD set featuring the underrated mid-20th-century Polish pianist Witold Małcużyński, part of the larger Icon series inherited from EMI.

Among the most notable recent additions in this deluge is an especially choice box from Decca (a label founded in 1929 and now part of Universal). Titled “Decca Sound: The Mono Years, 1944-1956,” the set follows two others devoted to Decca’s sonic and artistic legacy. But the excitement generated by this one rests squarely on its artistic value. Not that there’s anything wrong with the sound. Though the great leap forward in recording technology would come in the mid-1950s with the widespread adoption of stereo sound, late-mono Deccas were renowned for their relative realism, thanks to the company’s success in capturing increased frequency range (a byproduct of its efforts to help identify German submarines during World War II) and the arrival of long-playing vinyl records beginning in the late 1940s.

Though Decca has always been a proudly English company—hence its catalog’s outsize devotion to composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Walton and Britten—it has never allowed parochialism to cloud artistic judgment. Which is why the label proved so hospitable to an internationally celebrated roster of mid-20th-century performers. The conductors alone compose a map of Europe, with Ernest Ansermet (Swiss), Ataúlfo Argenta (Spanish), Adrian Boult (English), Eduard van Beinum (Dutch), Roger Désormière (French), Erich Kleiber (Austrian) and Georg Solti (Hungarian) merely the most notable. And all are represented (some more than once) by music long associated with them.

Special mention should be made of Ansermet’s vivid 1949 account of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” with the Geneva-based Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. It was Decca’s first LP and is fittingly this set’s first disc, coupled with Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” recorded by the same forces the following year. Ansermet and the orchestra, which he founded in 1918, became mainstays of the label until his death in 1969, but they were at their peak in the late-mono period.

The list of instrumental soloists is no less impressive, nor less international. The great German pianist Wilhelm Backhaus—who surveyed Beethoven’s 32 sonatas not once but twice for the label—appears in Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto and Brahms’s two cello sonatas (with Pierre Fournier). And the sublime English pianist Clifford Curzon, who set benchmarks for elegance and eloquence, offers those virtues in his 1953 recording of Brahms’s First Concerto. Connoisseurs of the violin can debate the merits of an idiosyncratic account of the Beethoven Concerto by the aged Mischa Elman, or pick from several works played by the ill-starred French fiddler Christian Ferras, whose Brahms Concerto may be a disappointment, but whose performance of Joaquin Rodrigo’s little-known “Concierto de Estio” proves as sunny as the summer it’s meant to evoke. And two discs headlined by the Italian-born, English violinist Alfredo Campoli should be required listening. His cogent and heartfelt 1954 performance of Elgar’s Concerto remains unsurpassed, and no assortment of Fritz Kreisler bonbons, including the composer’s own, evinces sweeter tone or greater charm than the one here.

Surprises abound in this collection—whether in terms of overlooked corners of the repertory or now largely forgotten but still worthy artists—but the most gratifying concern chamber music, an essential aspect of classical music too often neglected by large record companies. This collection pays proper tribute to the great British practitioners of the form by offering the Griller Quartet’s rigorous readings of four of Ernest Bloch’s five string quartets, as well as fleet performances of Mozart’s two piano quartets with Curzon and members of the Amadeus Quartet. But an even greater claim for the label’s sophistication comes from its engagement of Continental ensembles.

Those enamored of Danish music and musicians need look no further than the Koppel Quartet (named for a violist!) performing works by Carl Nielsen and Vagn Holmboe. And fans of the melodiously named Trio di Trieste will be delighted to find its relaxed performances of piano trios by Beethoven and Brahms. Even one of the world’s rare permanent piano quintets—known both as Quintetto Chigiano and the Chigi Quintet—gets star treatment, performing works by Boccherini, Brahms and Shostakovich. And for a taste Mitteleuropa, there’s the Végh Quartet in music by Schubert, Bedřich Smetana and Zoltán Kodály, and the Vienna Octet reveling in Mozart, Mendelssohn and Brahms.

One could say this box offers an embarrassment of riches. But why be embarrassed? Decca deserves only praise for fulfilling the long-held wishes of its core customers—and in such grand fashion, too. And collectors needn’t feel abashed at finally getting at least some of what they’ve long awaited. If there’s a quibble, it’s only to point out the absence of vocal music from this set—something Decca hints it will soon remedy. Until then, we can listen repeatedly to the treasures now in hand while insisting, in the best English tradition, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

Mr. Mermelstein writes for the Journal on classical music and film.

CD-1. Stravinsky: Petrouchka; Le Sacre Du Printemps

CD-2. Roussel: Le Festin de L'Araignée; Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin; Valses Nobles Et Sentimentales

CD-3. Rachmaninov: The Isle Of The Dead; Debussy: 6 Epigraphes Antiques; Jeux

CD-4. Albéniz: Iberia; Turina: Danzas Fantásticas; Poulenc: Les Biches

CD-5. Haydn: Symphonies Nos.101 & 88; Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.5 - "Emperor"

CD-6. Baranovic: The Gingerbread Heart; Lhotka: The Devil In The Village

CD-7. Bartók: Concerto For Orchestra; Pijper: Symphony No.3; Diepenbrock: Marysas

CD-8. Bliss: Colour Symphony; Introduction & Allegro; Violin Concerto

CD-9. Tchaikovsky: Suite No.3; Prokofiev: The Love For Three Oranges; Lieutenant Kijé

CD-10. Vaughan Williams: Job; The Wasps

CD-11. Britten: Sinfonia Da Requiem; Diversions; The Young Person's Guide To The Orchestra

CD-12. Homage To Fritz Kreisler

CD-13. Elgar: Violin Concerto; Works By Bax, Butterworth & Holst

CD-14. Walton: Façade; Lambert: Horoscope

CD-15. Elgar: Introduction & Allegro; Falstaff; Vaughan Williams: Greensleeves

CD-16. Mozart: Piano Quartets Nos. 1 & 2; Horn Quintet

CD-17. Brahms: Piano Concerto No.1 In D Minor; Beethoven: Symphony No.4 In B Flat Major

CD-18. Honegger: Symphony No.3; Beck: Viola Concerto; Reichel: Concertino

CD-19. Beethoven: Violin Concerto In D Major, Op.61; Haydn: Symphony No.102

CD-20. Brahms: Violin Concerto; Elizalde & Rodrigo Concertos

CD-21. Strauss, J.: Graduation Ball; Ballet Suites By Gluck & Grétry

CD-22. Tchaikovsky: Suites From "The Nutcracker" & "Sleeping Beauty"

CD-23. Brahms: Cello Sonatas Nos.1 & 2; Bach: Sonata In G

CD-24. Schubert: "Arpeggione" Sonata; Schumann: Cello Concerto

CD-25. Bloch: String Quartets Nos. 1 & 3

CD-26. Bloch: String Quartets Nos. 2 & 4

CD-27. Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos.26 & 29; Eroica Variations

CD-28. String Quartets By Haydn, Boccherini, Schumann & Verdi

CD-29. Sibelius: Four Legends; Karelia Suite

CD-30. Beethoven: Symphony No.9 In D Minor, Op.125 - "Choral"

CD-31. Beethoven: Symphony No.6 In F Major - "Pastoral"

CD-32. Bruckner: Symphony No.3; Wagner: Overture & Venusberg Music

CD-33. String Quartets By Nielsen, Holmboe & Sibelius

CD-34. Bizet: Jeux D'Enfants; La Jolie Fille de Perth; Chabrier: Suite Pastorale

CD-35. Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No.3; Khachaturian: Piano Concerto

CD-36. Mozart: Serenade In D Major, K.203; Symphonies Nos. 28 & 29

CD-37. Granados: Goyescas

CD-38. Lalo: Namouna; Fauré: Ballade

CD-39. Handel: Concerti Grossi Op.6, Nos. 1-5

CD-40. Handel: Concerti Grossi Op.6, Nos.6 - 10

CD-41. Handel: Concerti Grossi Op.6, Nos. 11-12; Water Music

CD-42. Rachmaninov: Cello Sonata; Kodály: Sonata For Solo Cello Etc

CD-43. Shostakovich: Piano Quintet; Bloch: Piano Quintet

CD-44. Boccherini: Piano Quintets; Brahms: Piano Quintet

CD-45. Paganini: Violin Concertos Nos.1 & 2

CD-46. Mozart: Symphonies Nos.25 & 38; Rossini: Five Overtures

CD-47. Bartók: Music For Strings, Percussion & Celeste; Kodály: Háry János; Haydn: Symphony No.101

CD-48. Beethoven: Piano Trio No.7 - "Archduke"; Brahms: Piano Trio No.1

CD-49. Prokofiev: Symphony No.5; Sibelius: Symphony No.5

CD-50. Nielsen: Symphony No.5; Concertos For Flute & Clarinet

CD-51. String Quartets By Smetana, Kodály & Schubert

CD-52. Mozart: Divertimenti K.334 & 247

CD-53. Mendelssohn: Octet; Brahms: Clarinet Quintet

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 1

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 2

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 3

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 4

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 5

Download | IsraCloud_FLAC_Part 6

Download | IsraCloud_320_Part 1

Download | IsraCloud_320_Part 2

Download | IsraCloud_320_Part 3

Download | IsraCloud_320_Part 4

Download | IsraCloud_320_Part 5

:: MusicMuss ::

![The Mr Bongo Edits, Vol. 1-4 (2022-2026) [Hi-Res] The Mr Bongo Edits, Vol. 1-4 (2022-2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-03/1742727562_mr_bongo_edits_collage_square.jpg)

![David Buckley - The Lincoln Lawyer (Soundtrack from the Netflix Series) (2026) [Hi-Res] David Buckley - The Lincoln Lawyer (Soundtrack from the Netflix Series) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/04/vzp86w0v1k1yvpz6k1s70okfi.jpg)