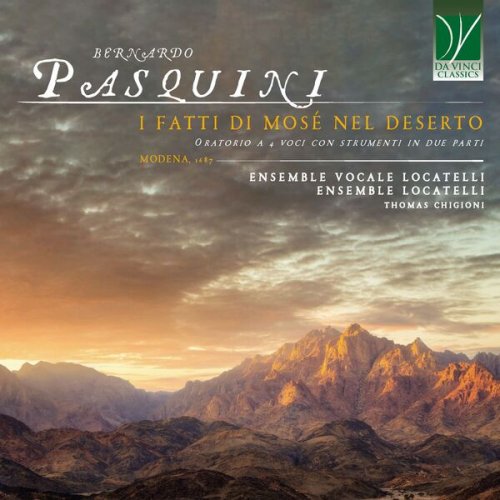

Locatelli Vocal Ensemble, Locatelli Ensemble, Thomas Chigioni - Bernardo Pasquini: I fatti di Mosé nel deserto (2025)

Artist: Locatelli Vocal Ensemble, Locatelli Ensemble, Thomas Chigioni

Title: Bernardo Pasquini: I fatti di Mosé nel deserto

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:18:55

Total Size: 387 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Bernardo Pasquini: I fatti di Mosé nel deserto

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:18:55

Total Size: 387 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Sinfonia

02. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 1: Recitativo Scorso già dell'Arabia (Narrator, Giosuè, Mosè)

03. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 2: Aria Quel diletto che sorprende (Mosè)

04. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 3: Recitativo, Del padiglione eccelso (Narrator, Getro, Mosè)

05. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 4: Aria Trattenete ò sfere il corso (Mosè)

06. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 5: Aria Qui chiudete ò fati amici (Getro)

07. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 6: Recitativo Ite, e sieno frà tanto (Mosè, Narrator)

08. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 7: Ritornello, Aria O gradita povertà (Narrator)

09. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 8: Recitativo Primo sugli aurei scanni (Narrator, Getro)

10. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 9: Aria Se fama immortale (Getro)

11. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 10: Recitativo Giuste son le tue brame (Mosè, Giosuè)

12. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 11: Aria Odi attento o Padre amato (Mosè)

13. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 13: Recitativo Poiché l'insano ardore (Giosuè)

14. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 14: Ritornello, Aria D'una fede al mio zelo (Giosuè)

15. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 14: Recitativo Ma qual mistero oh Dio (Getro))

16. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 15: Recitativo La sete estinta à pena (Giosuè)

17. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 16: Aria Ma nostre voci flebili (Giosuè)

18. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 17: Recitativo Quelle manne o miei figli (Getro, Giosuè)

19. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 18: Aria Dan del mondo le vicende (Giosuè)

20. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 19: Recitativo Piange l'ebreo sconfitto (Giosuè, Mosè)

21. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 20: Aria Che si farà mio Dio (Mosè)

22. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 21: Recitativo Così Mosè pregando (Giosuè, Getro)

23. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 22: Coro Sommo rettor del cielo (Chorus)

24. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 23: Aria Quella salma (Narrator)

25. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 24: Recitativo Dopo notte si cara (Narrator, Giosuè, Mosè)

26. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 25: Aria Chi sarà se non è Dio? (Mosè)

27. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 26: Recitativo Figlio, figlio a che spargi (Getro)

28. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 27: Aria A vil seno (Getro)

29. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 28: Recitativo Usa piuttosto o figlio (Getro)

30. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 29: Duetto Su, su, su, alla pugna (Mosè, Getro)

31. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 30: Recitativo Odi mio caro Giosuè (Mosè, Narrator)

32. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 31: Aria Campioni, seguaci (Giosuè)

33. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 32: Recitativo L'amalecita impari (Giosuè)

34. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 33: Aria Guerra, guerra (Giosuè)

35. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 34: Recitativo Fortuna il crin vi porge (Giosuè, Narrator)

36. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 35: Aria Che non fa del regnar (Narrator)

37. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 36: Recitativo Mosè fratanto asceso (Narrator)

38. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 37: Aria Mio Dio da cui cenni (Mosè)

39. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 38: Recitativo Sin che durò (Narrator, Mosè)

40. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 39: Aria Prima ch'io veggia (Mosè)

41. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 40: Recitativo Sul bivio della sorte (Narrator)

42. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 41: Aria Col zelo dal cielo (Narrator)

43. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 42: Recitativo Prece divota (Getro)

44. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 43: Ritornello, Aria Pupilla che sa piangere (Getro)

45. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 44: Recitativo Sceso Mosè dal monte (Narrator)

46. I fatti di Mosé nel deserto, Act I, Scene 45: Coro Stelle belle (Chorus)

In the first century of its life, the musical genre of the Oratorio knew an impressive growth, in terms of quantity (a proliferation of compositions), quality (some early works which are absolute masterpieces, and a plethora of excellent or very good Oratorios), subjects, and styles. Many of the greatest composers of the seventeenth century tried their hand in this genre, and for some it was one of the main veins of their artistic activity. In the early Baroque, the beating heart of this genre was doubtlessly to be found in Italy, with a particular focus in the city of Rome, whence it had originated thanks to the activity of the Florentine St. Philip Neri. However, the expansion of the genre also implied a geographical spread, which was the precondition for the Oratorio’s subsequent conquest of all European countries.

It was in Rome, however, that many of the most important Oratorio composers of the seventeenth century could be found. This was due, evidently, to the concomitance of a cultivated, wealthy, spiritually committed society centered around the Popes’ city; and of the limitations which periodically restricted operatic performances in the capital of Catholicism.

These conditions favoured the blossoming of many talents, as regards both libretto poetry and musical settings. One of them was Bernardo Pasquini, who penned the oratorio recorded, in world premiere, in this Da Vinci Classics production.

Pasquini was born in what is today the province of Pistoia, in Tuscany . Bernardo received his first musical education in Uzzano, and then moved to Ferrara, in today’s Emilia-Romagna. There he had the possibility of furthering his musical education. Living with his uncle, Giovanni Pasquini, he was encouraged to study with the musical elite of the city, which was one of the capitals of Italian culture in the Renaissance and early Baroque.

In 1655, at eighteen, Pasquini’s presence begins to be documented in Rome, as an employee of Innocenzo Conti, a Roman aristocrat. Five years later, Pasquini is identified as “Bernardo della Chiesa Nuova”, and this is highly meaningful since the Chiesa Nuova was the centre of St Philip Neri’s initiatives and spirituality. Pasquini was in fact the organist at the Chiesa Nuova from 1657 to 1664, thus absorbing the values and aesthetics of the very place where the Oratorio was born and whence it had taken its name.

The multiple occasions on which Pasquini is mentioned bear witness to his quick acceptance in the world of musical Rome, and, therefore, to the esteem and appreciation surrounding him.

In 1664, Pasquini’s career had a further upgrade, since he became the organist at Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the most important Roman Basilicas, and also acquired another important post in the magnificent church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. Pasquini was probably under the patronage of a Cardinal, Flavio Chigi, who was the Pope’s nephew, and with whom the musician went to the French Court in that same year.

Three years later, we find Pasquini under the wings of yet another nobleman, Giovanni Battista Borghese, who granted him a conspicuous salary, many benefits, and a stable job. With the Prince, Pasquini travelled to Venice, where they remained for many months, and this experience was certainly fundamental for encouraging Pasquini to try his hand in the field of opera.

His first opera dates from 1672: Il Tirinto was premiered in Ariccia, not distant from Rome, by one of the many Academies of art and culture (incidentally, the Accademia degli Sfaccendati is still alive and kicking in Ariccia). After Il Tirinto came L’Alcasta and Eliogabalo (in this case, the opera was not entirely written by Pasquini).

That decade of Pasquini’s life saw also a steady flow of Oratorios and spiritual Cantatas for the Borghese chapel; it is to be pointed out that the Borghese family did not claim exclusive property on Pasquini’s creations, which were performed both in Rome and in many other important cities such as Faenza, Ferrara, Florence, Lucca, Modena, Palermo, and Vienna.

In 1687, a work by Pasquini on a libretto by Alessandro Guidi was performed for King James II of England: there were more than 250 (!) performers involved – which should give us pause when we claim that small orchestras are the only “authentic” sound of Baroque music. The conductor of this monster ensemble was Arcangelo Corelli. Other highly prestigious cooperations enacted by Pasquini in those years involve the Bernini family – the architects of some of the most iconic buildings of Baroque Rome. No less important was Pasquini’s presence at the Colonna Palace, with several operas performed in the 1680s for this family, one of the main “clans” of the Roman aristocracy.

This network led Pasquini to write music for some extremely high-status occasions, several of which included a political dimension: for instance, he co-wrote, with Alessandro Melani and Alessandro Scarlatti, the music for a tragedy by Cardinal Pamphilj, premiered for the Ambassador of the United Kingdom.

Pasquini’s works in the fields of both opera and oratorios were frequently “exported” outside Rome, as has been briefly mentioned earlier, and his acquaintance with many ruling houses throughout Europe situated him in a very privileged position. Notwithstanding this, he remained profoundly devoted to the Roman aristocracy, and his last appointment was in the service of Giovan Battista Borghese’s son, Marcantonio. Still, there were also occasional tensions, especially when Pasquini’s duties vis à vis his employer conflicted with his service to others (as happened with the Medici family). Pasquini’s last years saw his progressive retirement from active musicianship and his careful ordering of some of his early works, especially for the sake of his many students. His obituary states that his house welcomed “all sovereigns who came to Rome at his time, and especially the Duke of Mantua, the Duke of Modena”, and some foreign Princes.

The Duke of Modena, indeed, presented Pasquini with a sum for making a ring, on the occasion of a journey he made to Rome in 1687. This was the same year in which the Oratorio recorded here was premiered, and this is certainly not a coincidence. Our Oratorio is one in a cycle of eight about the life and deeds of Moses, all setting to music the lyrics by Giovanni Battista Giardini: the scores were authored by several composers, including Vincenzo De Grandis (Il Nascimento di Mosè, 1682; and Il matrimonio di Mosè, 1684), Giovanni Paolo Colonna (Il Mosè, legato di Dio; this was the third Oratorio, premiered in 1686), Giacomo Perti (Mosè conduttor del Popolo ebreo, 1687 the fourth) and Bernardo Pasquini (the fifth). Later came La creazione de’ magistrati (1688) and Dio sul Sinai (1691), both by Antonio Gianettini, followed by Lo scisma del sacerdozio by Alessandro Melani (1691).

Giovanni Battista Giardini was the secretary to Duke Francesco II Este, the ruler of Ferrara, a city which was close to Modena both geographically and spiritually. It has been suggested that this grand cycle of Oratorios might have been conceived in the effort to affirm the greatness of the Jewish patriarch following the publication of a scandalous and blasphemous pamphlet which libeled him. In the words of Victor Crowther, this series of Oratorios is “a sophisticated blend of religion, politics, and dramatic entertainment that would give both instruction and pleasure”. Furthermore, and especially in the first librettos, a noteworthy openness towards the Jews and Judaism is found. Other allusions to contemporaneous politics may escape the attention of today’s readers, if they are not knowledgeable about the subtle dynamics of diplomacy between the French Court and the Estes (in particular, the Roi Soleil is frequently portrayed as the evil Pharaoh).

The subject of the Oratorio set to music by Pasquini regards the years spent by Israel in the wilderness, under Moses’ guidance. It is a subject which is found rather rarely in the Oratorio literature, although it is touched upon in Handel’s Israel in Egypt and features prominently in a (later) Oratorio by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

Pasquini’s Oratorio has been transcribed by Thomas Chigioni, the conductor of the Locatelli Ensemble, who observed the musical and visual beauty of the manuscript digitized by the Este Library in Modena. As Chigioni himself observes, “An aspect which fascinated me especially is the musical structure which is markedly centered around the continuo. This opened up the possibility of exploring different timbral combinations, to experiment with intertwining between instruments and sounds, and to leave a neat and personal interpretive mark on the work. It is a music which lives and breathes through the continuo; interpreting it means shaping it every time with a novel sensitivity. We were highly impressed by the musical quality of this work: it is an intense, theatrical music, extremely rich in expressive nuances, and – astonishingly – until now never recorded”. The performance recorded here took place at the Donizetti Theatre in Bergamo, and is a living testimony of the unique experience afforded by the rediscovery of this masterly score.

![Philipp Gropper’s Philm - Sun Ship (2017) [Hi-Res] Philipp Gropper’s Philm - Sun Ship (2017) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/22/lxfeu4bqs3xus6ku842hruzby.jpg)

![Clifton Chenier - The King of Zydeco (Live) (1981) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - The King of Zydeco (Live) (1981) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/xjfs68k4k2e6nw8a1vz89ft6c.jpg)

![Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res] Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/snzv0mdiaf2dg21tiqrm87jaq.jpg)