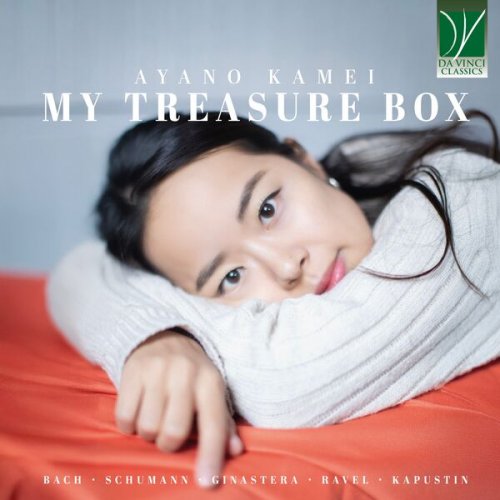

Ayano Kamei - My Treasure Box : Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alberto Evaristo Ginastera, Maurice Ravel, Nikolai Kapustin (2025)

Artist: Ayano Kamei

Title: My Treasure Box : Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alberto Evaristo Ginastera, Maurice Ravel, Nikolai Kapustin

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:56:35

Total Size: 163 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: My Treasure Box : Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alberto Evaristo Ginastera, Maurice Ravel, Nikolai Kapustin

Year Of Release: 2025

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 00:56:35

Total Size: 163 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Italienisches Konzert ; Concerto nach Italiænischen Gusto in F Major, Op. 2, BWV 971: I.

02. Italienisches Konzert ; Concerto nach Italiænischen Gusto in F Major, Op. 2, BWV 971: II. Andante

03. Italienisches Konzert ; Concerto nach Italiænischen Gusto in F Major, Op. 2, BWV 971: III. Presto

04. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 1, Von fremden Ländern und Menschen

05. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 2, Kuriose Geschichte

06. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 3, Hasche-Mann

07. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 4, Bittendes Kind

08. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 5, Glückes genug

09. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 6, Wichtige Begebenheit

10. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 7, Träumerei

11. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 8, Am Kamin

12. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 9, Ritter vom Steckenpferd

13. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 10, Fast zu ernst

14. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 11, Fürchtenmachen

15. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 12, Kind im Einschlummern

16. Kinderszenen, Op. 15: No. 13, Der Dichter spricht

17. Danzas Argentinas, Op. 2: No. 1, Danza del viejo boyero

18. Danzas Argentinas, Op. 2: No. 2, Danza de la moza donasa

19. Danzas Argentinas, Op. 2: No. 3, Danza del gaucho matrero

20. Trois chansons, M.69: No. 2, Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis (Piano Version)

21. La valse, M.72

22. Eight Concert Etudes, Op. 40: No. 1, Prelude

Japanese people know this well, but perhaps not all international readers will be cognizant of, or familiar with, this beautiful Japanese habit. A very special place in a traditional Japanese home is the “corner of the beautiful things”, tokonoma in the local language. It is the focal point of the home and of the room, and a small selection of artistic and/or natural masterpieces is displayed in it (incidentally, the very distinction between natural and artistic is much more Western than Japanese). And, once more different from Western culture, the guest’s place is not normally the one facing the tokonoma (i.e. in such a position as to fully enjoy the beautiful things collected there), but rather one in which the guest him- or herself becomes part of the “beautiful things”. It is a very refined kind of homage paid to the “beauty” – be it physical or moral or both – of the guest, which is considered as a “masterpiece”.

This Da Vinci Classics album resembles, in my eyes, precisely an aural tokonoma. It is made of masterpieces, some of which speak of nature, some of human beings, some of both; it is selected by the “host” who invites us to her musical home; and it involves the listener who is not considered as a passive user of music, but rather as a “masterpiece” in turn. Indeed, just as the personality of the pianist is the true red thread which unites the works recorded here, in the same fashion the listener’s personality is called to interact with the music, and to become part of it. The childhood memories which lie behind the artist’s choice of the pieces are called to elicit similar childhood (or adulthood!) memories by the listener, whose own life is invited to participate in this shared act of artistry.

Like an ikebana artist picking and selecting flowers, leaves, and other elements to make a beautiful composition for her tokonoma, the pianist drew from her repertoire the most significant examples of musical works which are meaningful for her. Here too there is a difference with Western attitudes: whereas for many Europeans or Americans a beautiful bunch of flowers is one with a great many flowers, for the Japanese a beautiful ikebana may have only a few flowers, but each of them is extremely valuable. So are the works chosen by the recording artist.

The Italian Concerto, which constitutes the first half of the second volume of the Clavier-Übung (among the few works he published during his lifetime) is a “fake” transcription from an inexistent Italian Concerto; the two-manual harpsichord is called by Bach to recreate the fullness of a Baroque Concerto grosso. After a broad, generous, lively first movement, the second movement is a masterpiece of lyricism, whose enchanting melodic line flows over the punctuations of the left hand, presenting a repeated bass and two higher parallel lines of inexpressible beauty. In the brilliant third movement, a quote from the Chorale In Dir ist Freude (“In Thee is Joy”) helps the listener in understanding the radiating joy of this Concerto as an expression of God’s Grace.

Schumann’s Kinderszenen is a set of short but touching and imaginative works. There are narrative pieces among these miniatures, such as the opening piece, which narrates of fabulous, exotic places, or the cheerful Kuriose Geschichte, or the pompous Wichtige Begebenheit, or the meditative, somber Fast zu Ernst. There are genuine “scenes”, such as games (Hasche-Mann, Ritter vom Steckenpferd, Fürchtenmachen), but also meditations on the mystery of childhood: pleading or praying children (Bittendes Kind), dreaming (Träumerei), contemplations of a time of unknowing poetry (Der Dichter spricht), along with other delightful pieces portraying slumbering children (Kind im Einschlummern) or young eyes fascinated by the fireplace (Am Kamin).

Going further in our itinerary, which is a true discovery of the corner of beautiful things prepared for us by the artist, we meet the Dances by Argentinian composer Ginastera. The most notable element here is the powerful rhythmic drive and the courageous, daring dissonances which however intertwine beautifully with the energetic vitality of the score. It constitutes one of the most notable elements of that fecund dialogue between Latin-American traditions and European (especially French) language, characterizing the late nineteenth and the twentieth century.

A propos of French culture, two further works are enclosed in this musical tokonoma. Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis (Three Beautiful Birds of Paradise) is a work rarely heard, and therefore it constitutes a fascinating discovery. It was originally a work for a-cappella choir, constituting the middle piece of a triptych of choral works, composed by Ravel on lyrics he had written himself. The context of their composition was that of the early period of World War I, a tragic moment whose importance Ravel could not underestimate. He wrote to a friend: “Since the day before yesterday this sounding of alarms, these weeping women, and, above all, this terrible enthusiasm of the young people and of all the friends who have had to go and of whom I have no news. I cannot bear it any longer. The nightmare is too horrible. I think that at any moment I shall go mad or lose my mind. I have never worked so hard, with such insane, heroic rage…Just think…of the horror of this conflict. It never stops for an instant. What good will it all do?”. The three movements were dedicated each to an influential person who, in Ravel’s opinion, could help him in his endeavour to be recruited in the army. These three pieces are powerfully reminiscent of Renaissance polyphony, and constitute three masterly achievements, unfortunately the only ones in Ravel’s oeuvre for unaccompanied vocal ensemble. Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis is the only one, among the three pieces, which openly speaks of war, although all three deal with loss. Here, the protagonist is a lady who intuits the death of her beloved upon receiving three Birds of Paradise, whose colours are those of the French flag (red, white, and blue).

In contrast with other works which are bound rather to folklore or to the more recent influences of jazz music, this work expresses the soul of a more intimate musical approach, which is complemented by the dazzling whirlwind of La Valse.

This composition was born originally as a creative idea through which Ravel had initially intended to pay homage to Vienna (in fact it was to be titled either Wien or Vienne). Later, legendary choreographer Diaghilev asked him to write a ballet score evoking the luxury and fascination of fin-de-siècle Vienna. However, the result did not correspond to Diaghilev’s expectations. Not without reason, he defined Ravel’s composition as a “portrait of a ballet” rather than a ballet proper. But this outraged Ravel, and ended their friendship. In spite of this, La Valse has been set to dance many times, and, in its concert form, has acquired extraordinary fame in the versions for solo piano, for piano duet, and for orchestra.

The album is capped by a brilliant Etude by Kapustin. The eight Etudes written by Kapustin in 1984 have quickly gained pride of place among the repertoire of piano Etudes, and they successfully manage to combine a distinctly modern approach with traditional piano technique and with a particularly amiable and friendly style, which easily conquers the listeners. References to Latin-American music, or to the North-American jazz and pre-jazz tradition are abundant, and the result is engaging as well as breath-taking.

The listener is therefore invited to savour the beauty of this aural tokonoma, and, of course, to become a part of it, in conformity to the tradition and practices of Japanese etiquette and friendliness.

![Coco Chatru Quartet - Lost Christmas (2025) [Hi-Res] Coco Chatru Quartet - Lost Christmas (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765719561_coco-chatru-quartet-lost-christmas-2025.jpg)